Rethinking Growth

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/Cover_Image_EN_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act looks at smart growth, from efficiency and ideal group size to dark tourism, sports technology innovation at FC Barcelona and the data gender gap.

by Fred Schulenburg

illustrations by Supertotto

Three of today's leading economic minds are challenging us to reconsider the way we view growth. One common thread runs through them all: it's time to slow down.

After a period of disillusionment with economics, Kate Raworth worked in development and at the UN before returning to economics. She says that right now we are nowhere near her vision of a more harmonious economy.

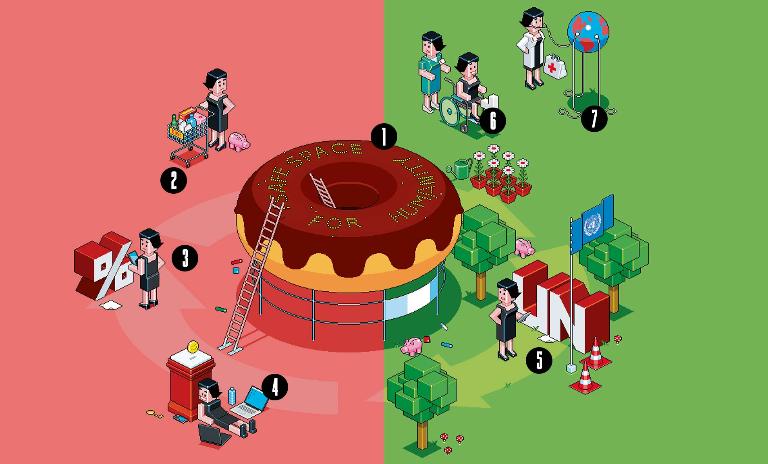

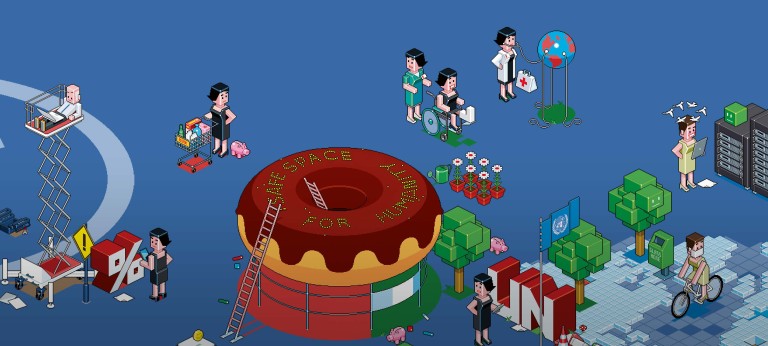

Doughnuts are not normally associated with a balanced, healthy approach to life. Yet for the economist Kate Raworth, the doughnut is a useful symbol. Raworth makes the doughnut akin to a compass. It can, perhaps, guide us toward a reworking of economics, a 21st-century overhaul. We need to find a better and more virtuous cycle of labor and reward that takes into account the currently ignored elements – the environment, social, and domestic elements – which the doughnut's shape helps to represent.

People need to be protected by new measures to help keep them in society's embrace – the sweet spot of the doughnut’s "ring." In Raworth's model, there are resources we need for a good life, such as food, clean water, housing, energy, education, health care, and democracy. The hole in the doughnut represents an area of deprivation of those needs. Beyond the doughnut are the Earth's environmental limits, such as climate change, water pollution and other problems with the natural world. So the area between those two positions is the ecologically safe and socially just space to inhabit, which in her example is the ring of the doughnut itself. You can see key elements of the problem and solution in the graphic to the left.

A sugary pastry helps illustrate how we need to account for social needs, well-being and the environment.

The history of economics, Raworth argues, is one of "raising our sights." She looks back to classical Greece, where "economics" referred to household management and was later extended to the city-state of Athens. Adam Smith then extended it to the nation-state 2,000 years later. Were they here today, they would demand that we adapt our approach to the planetary age. This is the "most exciting task" for the new generation of economists. Investing in human, natural, and social wealth will help sustain humanity. Perhaps her doughnut can help us find a balance and live in the sweet spot where everyone has enough and the planet can support it all.

The Cambridge University professor and author of GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History aims at a more complete accounting for growth.

A map on which some bits are quite clear and others quite faint – or perhaps even just blank. That's how Diane Coyle sees the current picture of economic growth and our attempts to define and measure it. And she has ideas about policies that need to be introduced to improve lives and reset our thinking.

Coyle thinks that businesses and nations are ignoring many of the critical items that contribute to growth today. The overall result, she argues, is a somewhat partial account of growth, which in turn results in an incomplete basis on which policy choices are being made. Her analysis has led her to the idea of a chart that needs filling in.

Changing all of this will not be easy. Individual action, whether taken by people or by companies, will have limited effect. "Changes in [accounting] frameworks are driven by crises, often conflict," says Coyle. "We got the GDP we have because of World War II." Conflict – combined with a fundamental change in economics, such as through the emergence of new technologies – is what drives realignments in thinking as well as in methodology.

The question for her now is whether we are at such a tipping point. Does the current discontent with the limits of our understanding as to what constitutes growth crystallize into a movement for change? She is cautiously optimistic and says that she sees evidence of a real change in attitudes to growth – and that is proving especially true within the business world. Still, she argues, that change is only truly possible if collective efforts are made across multiple fronts. She suggests a "plural approach" – from professional bodies, at the industry level, through national accounting frameworks and up to international institutions such as the G7 group of the world's richest economies. This will boost awareness and also change the way in which we perceive growth going forward.

Professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba, Canada, Smil's ideas are referenced by economists and revered by leaders such as Bill Gates, who has said he looks forward to a new Smil book the way other people do the next Star Wars movie.

"There are limits everywhere," says Vaclav Smil. "Of course growth has to come to an end. No trees grow to heaven." The environmental scientist has spelled out his thoughts in his recently published book Growth: From Microorganisms to Megacities. He claims that as a resident of "flyover country" – the central expanse of North America that most only see from the air – he is a voice on the margins of the economics debate.

Smil argues that we have become confused between quality and quantity growth – and that humankind has reached the "pinnacle of irrational stupidity" in how we consume. Things have to stop – the challenge is how to do so. "Single, simple solutions" – like the blanket application of a fee to offset the environmental costs of various goods, services, or activities – are not the answer, he says. While putting a price on behavior might work in an egalitarian society, in inegalitarian ones, which increasingly applies to the US, implementing such a charge will hit the poorer members of society the hardest.

A more nuanced approach at various levels, Smil argues, would be a better way to address the problem. "Voluntary abnegation" – individual decisions to scale back and eliminate waste – is one starting point. Another is to establish greater transparency about the "real" price of the goods that we buy. "We pay no fair price for anything. There are subsidies everywhere," says Smil. "We don't know the real price for bread, cheese or gasoline." He adds: "We need to get to those numbers and start acting on them."

The response needs to be graduated, given the unintended consequences of simply relying on price as a tool for changing behavior. The critical step is establishing awareness of the facts. Above all, a key step toward addressing the current challenges needs to be changing our own conception of growth and realizing that "ever onwards and upwards" is not a rational approach.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/Cover_Image_EN_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act looks at smart growth, from efficiency and ideal group size to dark tourism, sports technology innovation at FC Barcelona and the data gender gap.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.