Embracing the unknown

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta_34_001_en_cover_download_preview.jpg)

Nothing could have prepared us for the end of predictability. Think:Act magazine explores how we can plan for an uncertain future.

by Bennett Voyles

Photos by Wolf Heider-Sawall, Francesco Guidicini, Robert Markowitz, Tina Krohn

Read more about the topic "The Unknown"

At the sharp end of a life-and-death decision, you might have to act very quickly. How do you prepare? Four professionals at the cutting edge share how they learned to handle the unknown and unpredictable lying ahead.

A pandemic was always a possibility, but when it became a reality last year, it presented many executives and entrepreneurs with extraordinarily difficult choices about how to take care of their staff, their customers and their business. It wasn't a case of dealing with the unknowable or the unknown, but it was unpredictable and it did require rapid reaction to a changing environment. For some professionals, this kind of quick decision-making under extreme conditions is all in a day's work. So what can you learn from them? We talk to a brain surgeon, an astronaut, a spymaster and a mountaineer about what it takes to operate with grace under pressure when a steady stream of life-and-death decisions is just part of the job.

Age: 50 years

On call: Her background as a nurse is something she credits for helping her better deal with the transience of life.

Power of mind: She makes visualization and meditation part of her daily routine: "They help me master the most difficult situations, allow me to keep calm in situations that seem hopeless and enable me to make the best possible decisions."

The first woman to scale all 14 Himalayan and Karakoram 8,000-plus-meter peaks without using oxygen, the Austrian climber prepares for tough decisions long before she takes her first step up the mountain.

"I think it is extremely important to talk about certain scenarios that may occur during the climb before the expedition," she says. But although Kaltenbrunner invests a lot of time and energy in detailed planning ahead, she is quick to adjust her plan if conditions change. "On such occasions, I have always trusted my gut feeling, which has become more pronounced and stronger over the years. I know I can rely on it."

"If there is a lot of snow and high winds, the avalanche danger is often too great to climb, which means we have to change plans and wait for the conditions to improve," Kaltenbrunner says. "Sometimes we have to wait for days or even weeks, but most of the time our patience gets rewarded and we can climb in good conditions and fine weather. High-altitude mountaineering certainly teaches us to slow down and be patient, as this is the only way to have a successful expedition."

Even after major reversals, such as the death of teammate Fredrik Ericsson on their first attempt to scale K2 in 2010, Kaltenbrunner later decided to try again. "Basically, I am convinced that life is for us and not against us, and we should look forward and not back," she says. "I consciously decided to trust in life again."

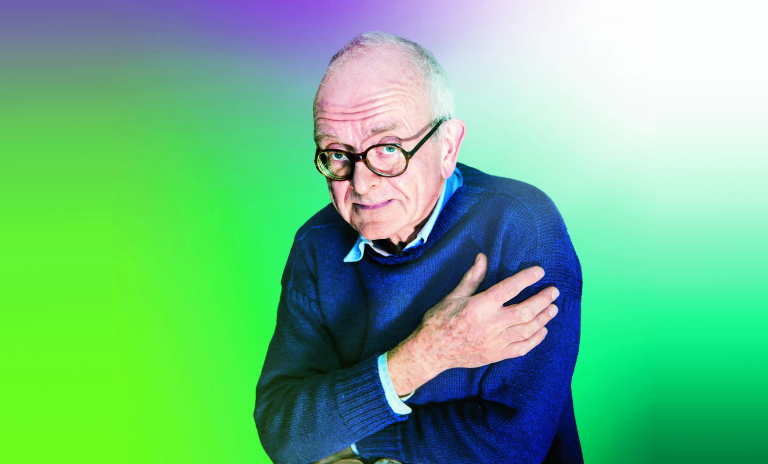

Age: 71 years

Author of: Do No Harm, Admissions

Feedback matters: He pioneered techniques for operating under local anesthetic so patients are conscious and able to talk during their procedure.

Well documented: He is the subject of two BBC documentaries: Your Life in Their Hands and The English Surgeon.

Henry Marsh has seen thousands of brains and made hundreds of difficult decisions about what to cut and what not to touch, knowing that his next move could mute, paralyze or even kill his patient.

"If you are too self-confident, you may well fail in estimating risk and benefit between operating and not operating. It is all too easy to underestimate the risks of operating and overestimate the risks of not operating. The best way of overcoming your cognitive biases – which you can never do completely – is to make decisions slowly and thoughtfully and afterwards discuss them with critical but sympathetic colleagues. "One kind of bias in particular, confirmation bias – interpreting the data based on what you already expect the answer to be – is the biggest risk for a neurosurgeon, according to Marsh. "If you make the wrong decision, it is remarkably difficult to realize it until it is too late because of the confirmation bias. You will misinterpret the evidence that things are going wrong and try to understand them in terms of your initial mistake."

"Asking for help is a sign of strength, not of weakness."

Mistakes, Marsh says, don't happen very often during surgery – but when they do, it's important to stay calm. "Most mistakes are in pre-operative or post-operative decision-making. But if it does happen, the important points are that the patient and family have been warned that this might happen and to keep cool. Keeping calm – or 'frosty' as a jet fighter pilot friend of mine says – is partly a question of your personality, training and experience."

"With experience, you know that usually you will be able to sort the problem out. If you are inexperienced, you need to be able to call for the help of a more experienced colleague. Sometimes this involves overcoming your ego and pride. Asking for help, I tell my trainees, is a sign of strength, not of weakness."

Age: 57 years

Author of: Endurance, my Journey to the Stars

Flight record: He holds the USA's No. 1 spot for the longest single flight in space: 340 days on the ISS.

Twin purpose: His record ISS flight measured the effects of extended stays in space against his twin brother, fellow former astronaut and current US Senator for the state of Arizona Mark Kelly, who stayed on the ground.

Now retired from NASA, Kelly once held the record for more time in space than any other US astronaut – 520 days in total including a one-year tour of duty on the International Space Station (ISS).

"I think part of leadership and teamwork is taking care of each other ... checking in on each other: How are you doing? How are you feeling? How are things at home? How’s your family?"

"Oftentimes, I’ve found it makes more sense to seek out who may know more about what you’re trying to do than you do."

Kelly credits his ability to focus under pressure in part to a tough childhood. "When I grew up, my parents didn't get along very well and there was a lot of stress and conflict in our house, so I think that prepared me well for dealing with stress and conflict," Kelly says. Later, the military trained him further in what he calls a "philosophy of compartmentalization," the basic idea of which is "there are things we have control over and things that we don't have control over – and better to focus your efforts and attention on the stuff you can control and ignore everything else," Kelly continues. "I think that kind of helps in dealing with stressful situations in a calm way."

"Sometimes it makes sense to be the dictator – when there is a fire and you are in space and you need to make split-second decisions," Kelly says. "But oftentimes, I've found, it makes more sense to seek out the person of your team who may know more about what you're trying to do than you do or what the situation is than you do and let them decide or get their opinion."

Age: 73 years

Author of: Principled Spying, How Spies Think

Social intelligence: He co-wrote the first study on "SOCMINT" looking at the use of social media for intelligence purposes.

Just ethics: Principled spying lays out an "ethical code for secret intelligence" that follows the "just war" theory criteria.

From Margaret Thatcher to Tony Blair, Sir David Omand spent a lot of time "in the room where it happened" when some of the United Kingdom’s most important military decisions were made.

"The art of crisis management is to see this coming before it arrives."

There are two kinds of crises, Omand says: the sudden impact crisis and the slow burn. Of the two, the slow burn is the most difficult. "If you are faced with a sudden impact crisis, you have no alternative but to react. But if it's a slow burn crisis, this is much more difficult, because at some point a developing situation reaches a tipping point. The art of crisis management is to see this coming before it arrives ... You may not be able to avoid it, but you can start to mitigate it. You can prepare."

"Having a lot of information coming in isn’t of itself that useful. You need to take the time to build some model of whatever the potential hazard is that you're looking at, so you've thought in advance about what information is going to be most useful and you can fit it into some framework ... You have to be prepared to interrogate the data, question the data, because by itself [data] often can be extremely misleading."

It's important to remember that anyone making an important decision brings two kinds of thinking: emotional and rational. Complicating matters, says Omand, is the fact that "these days, you can also find emotional stuff in the supposedly rational analysis ... the basic information you're working with is not as reliable as you think it is," he explains. "The other problem is simply the cognitive biases that we are all susceptible to. So even if you've got really, really good information, you can still deceive yourself because of unconscious biases.'' One method he advocates for making a good decision: "Appoint a devil's advocate. Say, 'your job for the next hour is to pick holes in the argument.'"

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta_34_001_en_cover_download_preview.jpg)

Nothing could have prepared us for the end of predictability. Think:Act magazine explores how we can plan for an uncertain future.