Rethinking Growth

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/Cover_Image_EN_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act looks at smart growth, from efficiency and ideal group size to dark tourism, sports technology innovation at FC Barcelona and the data gender gap.

by Janet Anderson

illustrations by David Despau

British anthropologist Robin Dunbar has identified the optimal number of people for social groups. So before you think about growing your team or business, you would do well to consider how Dunbar's number might be able to help you achieve maximum efficiency in the very best network.

The structure of our minds is such that we can’t really handle very large numbers of relationships. We use tricks to create massive conurbations, nation states, global businesses, but in reality, our social world is very small-scale," says Robin Dunbar, emeritus professor of evolutionary psychology at the University of Oxford.

In the Northwest of England, close to the city of Liverpool, the rivers Mersey and Dee form a peninsula known as The Wirral. This is where Robin Dunbar is "hiding away" to work on his latest book about friendship and community. He has spent much of his career thinking about these questions. Indeed, his research is concerned with trying to understand the behavioral, cognitive and neuroendocrinological mechanisms that underpin social bonding.

His motivation was clear. "I set out to resolve a dispute in primate literature about grooming. Primates spend an inordinate amount of time on grooming. Conventionally this was seen as just a form of hygiene," says Dunbar. "I speculated that there was more to it: Why do some species invest about 1% of their time and others 20% performing this task – even with the same amount of fur?" He proposed that the function of grooming had in fact been co-opted as a social bonding mechanism and looked at how this correlated to social group size. "The more individuals there are in a group, the more time is spent on bonding," he says. Following the social brain hypothesis, which assumes that primates have big brains because they live in complex social groups, there had to be a three-way correlation consisting of brain size, group size and time spent grooming.

"The size of the business unit can affect success."

This was indeed the case and these findings prompted Dunbar to see if they could be translated to human social groups – to predict what the human group size ought to be given the size of our brains. The number turned out to be 150. "It seemed small, so I set out to see if it exists," he says. He started by collecting data about hunter-gatherer societies – the kinds of societies we have lived in since our earliest evolutionary days – and arrived at the same number. Soon after, the number was turning up everywhere, in all areas of contemporary life: The smallest unit that can stand on its own in modern armies is the company, which has a range in size of about 120 to 180 around the world. It is also the size of a small village, tribe or clan. A hundred and fifty turns out to be the limit on the number of people we will naturally cooperate with.

Dunbar’s number, first proposed in the 1990s, quickly became a magical figure. Dunbar, himself reluctant to join internet-based social platforms, was unexpectedly labeled the guru of social networking. "It took me by surprise how it got latched on in the internet world," he says. In an age of unprecedented connectivity, several important questions arise with this evidence that the structure of our minds can't handle very large numbers of relationships: How do human societies respond to our brain's intrinsic limitations? Do human communities in the shape of clubs, businesses, associations or government departments structure themselves naturally? And if they don't, what kind of constraints does that impose on them?

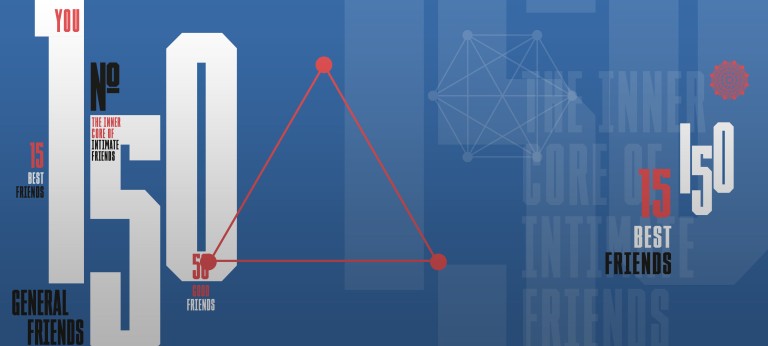

"It is worth looking at how human relationships shape, how group sizes scale up and define characteristic behavior. Like ripples set in motion by a pebble thrown into a pond, social relationships form around you in a series of layers with distinct sizes and scaling ratios," Dunbar explains. At the center, tightly knit relationships of approximately five shape the intimate core. These are the people who would drop everything to come to your aid. The pattern continues: 15, 50, 150, 1,500. "The members of a football team, for example, know each other so well, they are in each other's minds," he says. Relationships are determined by the economies of time and emotion, investment and return. We put a lot of effort into our inner circle and are in turn rewarded with emotional support. We are more frugal when it comes to remoter layers and consequently the benefits received from these layers of relationships decrease proportionally.

The principle also applies to more task-oriented contexts of the business world. Wherever people must cooperate and perform together, there are natural limits to the number of people we can do that with. Groups of around 150 originally formed to protect against raiders. Small-scale agricultural societies help each other during harvest without payment. They are very much based on close kinship, families and clans. Even without instant gratification there are long-term benefits resulting from such behavior. But no matter whether there are implicit or explicit agreements in place, beyond that number, people are less inclined to reciprocate and help.

"Moving to the outer spheres, that's where the people are that we see daily; colleagues, people we happily have a cup of tea with now and again but probably wouldn't invite to our big 50th birthday party," Dunbar says. "At around 500-strong, these people are acquaintances, and they tend to remain just that." At the level of 1,500 people, relationships change again. "This is the typical size of a tribe," says Dunbar. The distinguishing characteristic of these relationships is that they are strictly one-dimensional. The mechanisms used to bond these large groups in the past involved cultural characteristics like singing, dancing and storytelling. Today, we use other mechanisms.

Indeed, in today's world humans have become very adept at exploiting one-dimensional relationships that scale up extremely well – this is the fabric that holds larger communities together such as religious organizations, political movements and large companies. The binding force is often a common belief, value, interest or sense of purpose. However, these large groups collapse very quickly if that common element evaporates.

"If we look at the business world, explicitly task-oriented relationships tend to be weak and of short duration. A recent analysis of friendships among banking professionals in Chicago found that close relationships lasted on average only for six months as opposed to typically three years for non-family friends. People simply moved on constantly. With the common goal disappearing, there was simply not much reason to carry on," says Dunbar. Similar relationships are found within the world of online gaming. They are alliances that serve as purely functional, created for a specific task at a certain stage of the game, and they only last until the task is completed.

In the business world, these insights offer some valuable lessons for maximizing team interaction. "The sociology of business shows that the size of the business unit can affect success. In units smaller than 150, more friendships are formed. Above 150, the sense of common purpose weakens," says Dunbar. Large organizations run the risk of infighting. Rivalries build up between departments and employees are reluctant to keep management informed about problems.

The conclusion is that it is better to install smaller units that are semi-independent of each other. But that is not all. Success may also hinge on providing a sense of purpose beyond pure function. "There are businesses that work very hard to achieve a sense of community. And it really matters," says Dunbar. "We need a common sense of belonging – a totem pole in the middle of the village green where we can all hang our jackets."

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/Cover_Image_EN_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act looks at smart growth, from efficiency and ideal group size to dark tourism, sports technology innovation at FC Barcelona and the data gender gap.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.