Roland Berger advises the aerospace, defense and security industries. We support OEMs, suppliers, agencies and investors.

COVID-19 – How we will need to rethink the aerospace industry

Plunge in air traffic will deeply impact demand for new aircraft

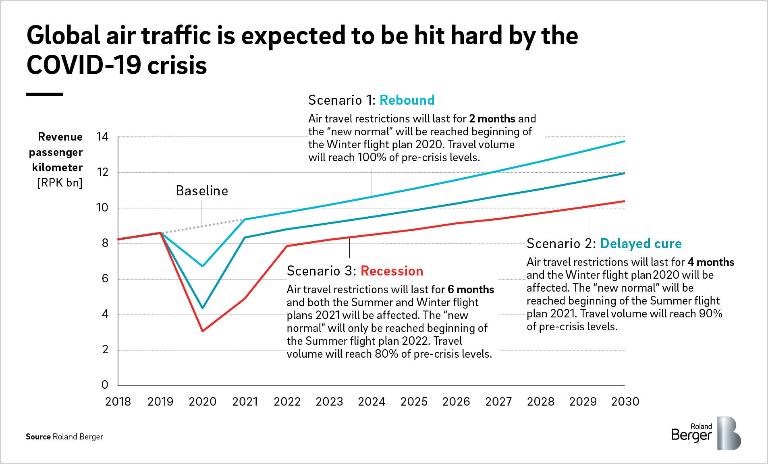

The Covid-19 pandemic has the potential to trigger a global economic crisis of significant dimensions, affecting all industries. One of the industry sectors in the eye of the coronavirus storm is aerospace. Global air traffic has been brought to an almost complete standstill by the Covid-19 outbreak. While air traffic has consistently shown a solid recovery from previous crises, the debate is wide open about how traffic will recover following the current crisis and what this will mean for the civil aircraft manufacturing industry, the supply chain and aftermarket support businesses.

Previous crises like 9/11, SARS or the financial crisis of 2008/09 all demonstrated a recovery along V- or U-shaped curves back to the pre-crisis growth path. As Covid-19 is a fully global crisis of unprecedented magnitude, we need to consider whether we might see an L-shaped recovery with consistently lower levels of air traffic and permanently slower growth after the crisis.

The debate is fueled by two questions for which there is no real precedent to extrapolate from but which could be transformational for the industry:

- What is the magnitude of the Covid-19 crisis, and will it change the way we perceive air transport?

- Will the crisis highlight obsolete industry structures and cause the bubble of huge aircraft orderbooks to burst?

This article discusses three key questions:

- 1. How deep will the crisis be for aviation, and how long will it last?

We examine different scenarios for global air traffic development in the coming years. - 2. What will be the impact on the aerospace industry?

We derive the impact of these scenarios on the demand for new aircraft and MRO (maintenance, repair and operations). - 3. What needs to be done to manage the crisis?

We discuss what the aerospace industry could look like in a post-Covid-19 world and what measures need to be taken to mitigate risks and capture opportunities.

1. How deep will the crisis be and how long will it last?

The magnitude of the air traffic crisis can be characterized by four key indicators:

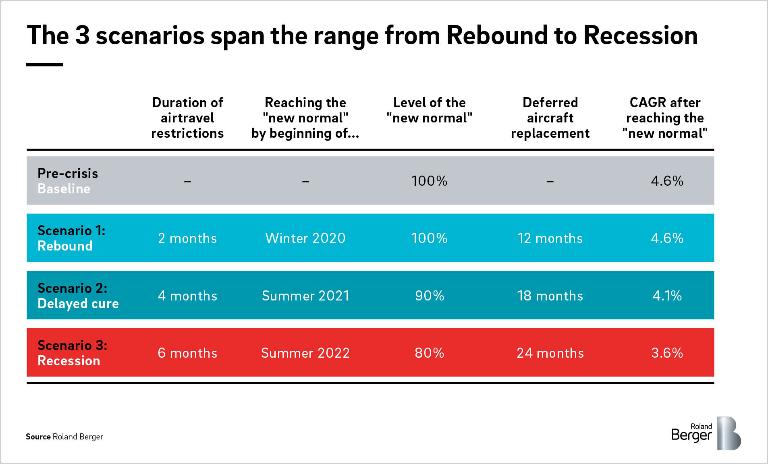

With a fast recovery, i.e. a return to pre-crisis traffic levels during the summer flight plan 2020, already ruled out, we have developed the following three scenarios:

- Scenario 1: Rebound

Air travel restrictions will last for two months and the "new normal" will be reached beginning with the winter flight plan 2020. Travel volume will reach 100% of pre-crisis levels. - Scenario 2: Delayed cure

Air travel restrictions will last for four months and the winter flight plan 2020 will be affected. The "new normal" will be reached beginning with the summer flight plan 2021. Travel volume will reach 90% of pre-crisis levels. - Scenario 3: Recession

Air travel restrictions will last for six months and both the summer and winter flight plans for 2021 will be affected. The "new normal" will only be reached beginning with the summer flight plan 2022. Travel volume will reach 80% of pre-crisis levels.

While more accurate values for the possible outcomes across the scenarios will become much clearer in the coming weeks and the scenarios will need to be refined, this first assessment already gives a ballpark view of the range of possible futures for global air traffic.

2. What will be the impact on the aerospace industry?

We took these three scenarios for global air traffic as a basis to model demand for new aircraft and MRO services, considering retirements of older aircraft, potential deferrals or cancellations of current orders, a dramatic slowdown in new aircraft orders, and the consequent evolution of the fleet.

Demand for MRO services is primarily driven by the size and flight activity of the global fleet, albeit with some complex transitory factors. As soon as aircraft are grounded, demand for all flight hour/flight cycle linked maintenance disappears (although calendar time-based maintenance remains). Thus, MRO is hit first in any downturn, and MRO providers and spare parts suppliers suffer immediately. As aircraft return to flight, MRO activity picks up, but MRO shops first consume existing inventory before purchasing new parts from suppliers. In addition, aircraft that have been grounded may be disassembled and their parts used as spares, further reducing demand for spare parts from equipment suppliers.

The picture is very different when it comes to the demand and production of new aircraft. As a pre-crisis reference point, we took the industry consensus of global aircraft demand for 2020-2030, which predicted that the market needed around 21,760 new aircraft over the next ten years.

As a result of the crisis we must assume that cash-constrained airlines will postpone scheduled aircraft replacements, especially as current fuel prices will make it economic to continue to fly relatively older, less fuel-efficient aircraft.

We therefore plugged the following assumptions into our model:

· Scenario 1 (Rebound): Replacements postponed for 12 months

· Scenario 2 (Delayed cure): Replacements postponed for 18 months

· Scenario 3 (Recession): Replacements postponed for 24 months

Although not included in the model at this stage, it is worth noting that there is an additional risk of replacement cycles being extended after the initial postponements, especially if the oil price remains as low as it currently is.

Depending on the scenarios for global air traffic development, the overall aircraft demand 2020-2030 varies significantly.

Scenario 1 (Rebound)

In scenario 1, a prolonged V-shaped scenario, the industry is only mildly affected. The demand for new aircraft comes to a halt in the next 12 months and then reverts to the pre-crisis demand curve. The cumulative demand for new aircraft over the next ten years therefore drops by only 800 aircraft (-4%) as a result of the small-scale postponement of replacements. The key issue for the industry will be to maintain production at a level that allows it to quickly ramp back up to previous levels while safeguarding liquidity.

Scenario 2 (Delayed cure)

The ten-year demand for new aircraft in scenario 2, a U-shaped scenario, drops to 15,840 new aircraft (-27%), driven by both the postponed replacement of existing aircraft and the lower level of air traffic in the future. The latter has a far more significant impact on demand for new aircraft, and in this scenario the industry will be forced to downsize its operations significantly. In addition to the reduction in the number of aircraft, it can be assumed that the lower level of traffic will also affect the replacement strategy and the product mix in the fleets. For example, an A220-300 may replace an A320 or a B787-8 may replace a B787-9 to make up for the lower number of passengers on given routes.

Scenario 3 (Recession)

These effects are even more pronounced in scenario 3, an L-shaped scenario. The low volume of travel (80% of pre-crisis levels) and lower growth in the "new normal" result in a drop in new aircraft demand of almost 50% over the next ten years. Changes to the replacement strategy and the product mix in the fleets as described in scenario 2 will also be more significant. This scenario will inevitably result in a heavy downsizing and restructuring of the whole industry and supply chain.

The scenarios highlight that demand for new aircraft will fall significantly in the short term and may not return to pre-crisis levels in the medium term. Of course, this must be offset against existing aircraft OEM orderbooks and the airlines' contractual obligations to purchase already ordered aircraft even though the demand for them may have evaporated. However, faced with the extreme situation of the Covid-19 crisis and looming airline bankruptcies, the robustness of each individual order must be open to question.

In sum, the aircraft manufacturing industry faces three major challenges:

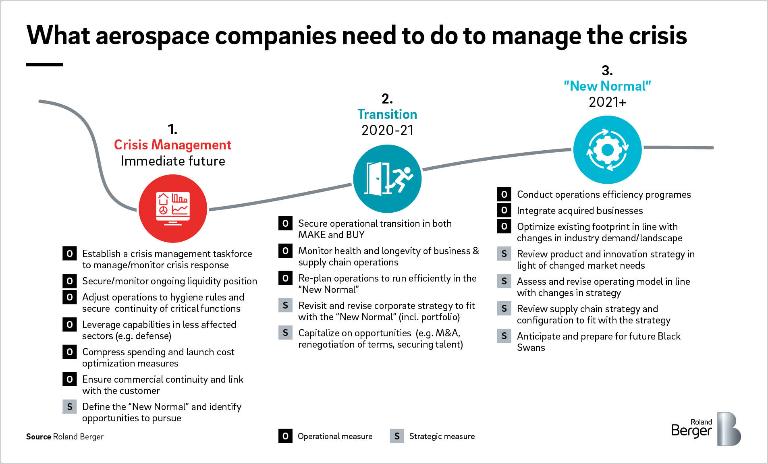

3. What needs to be done to manage the crisis?

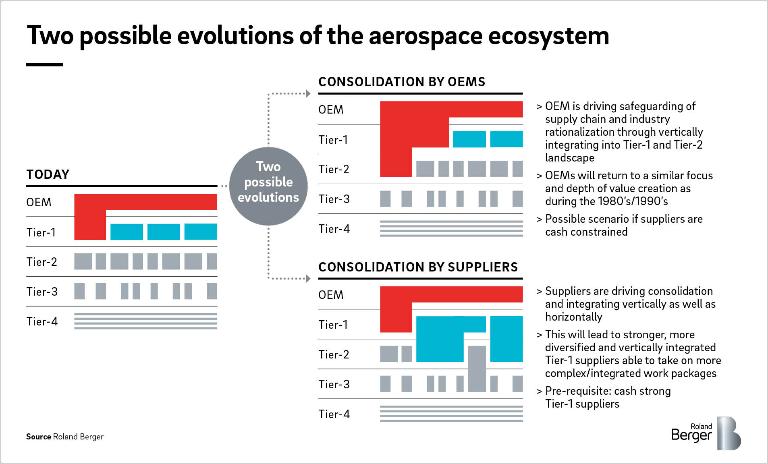

It can already be anticipated that the post-crisis aerospace industry will not look like it did before the crisis:

- Significant downsizing of operations is to be expected for both OEMs and suppliers – the industry will need to offset the resulting loss of scale with a step up in efficiency, potentially taking advantage of the crisis to take actions that would be unpalatable in easier times.

- Weaker suppliers (e.g. those with heavy exposure to the B737, more aftermarket exposure and less counter-cyclical defense business) will come under severe financial pressure.

- A significant consolidation of the industry by companies with strong balance sheets must be expected, either to take advantage of distressed assets or to bail out suppliers to safeguard the stability of their supply chain.

One of two possible post-crisis industry models could emerge:

- 1. A more OEM-centric industry model whereby the OEMs consolidate key parts of the supply chain to stabilize and rationalize it.

- 2. A more balanced industry model between OEMs and key Tier-1 suppliers, where the Tier-1s have consolidated even more, amassed scale and are now on a level playing field with the OEMs.

As the aerospace industry relies on a highly interconnected and mutually dependent supply chain, the crisis needs to be managed on two levels in parallel:

On an individual company level, cash will be king. Protecting cash positions will be key to ensuring survival while managing the ramp-down, stabilizing and securing the supply chain and seizing opportunities in the market – we may therefore expect a cash squeeze in May and June as new production schedules become established but activities have not yet been rationalized. Preparing for the "new normal", rightsized and potentially repositioned operations must start immediately. To this end, the company's strategy, its industrial footprint and operating model, needs to be reviewed and a blueprint developed to fit with the "new normal" and provide the right framework for short-term actions and strategic moves.

At industry level, companies and governments will need to work closely together to ensure that key industrial capabilities do not fall through the cracks, as this would put the whole industry at risk. Therefore, the industry will have to:

- Quickly reach a consensus on the "new normal" production rates

- Define a joint plan for how to transform the industry from its status quo to the "new normal" level

- Identify at-risk elements in the transition process and develop plans to support them

Once this picture is clear, government support may need to be called upon to safeguard the short-term functioning of the industry and help manage the transition to the "new normal" for this strategically important sector.

Get in touch with our experts and receive our latest insights.

_image_caption_w1280.jpg?v=770441)

_image_caption_w1280.jpg?v=770441)

_image_caption_w1280.jpg?v=770441)

_image_caption_w1280.jpg?v=770441)