Can bikes and scooters change our cities?

Shared micromobility could become a genuine alternative to cars and complement public transport

Are e-scooters and rental bikes a fad or can they be a smart contribution to urban mobility? In the study "Mobilizing micromobility | How cities and providers can build a successful model", Roland Berger evaluates best practice examples and formulates seven key success factors.

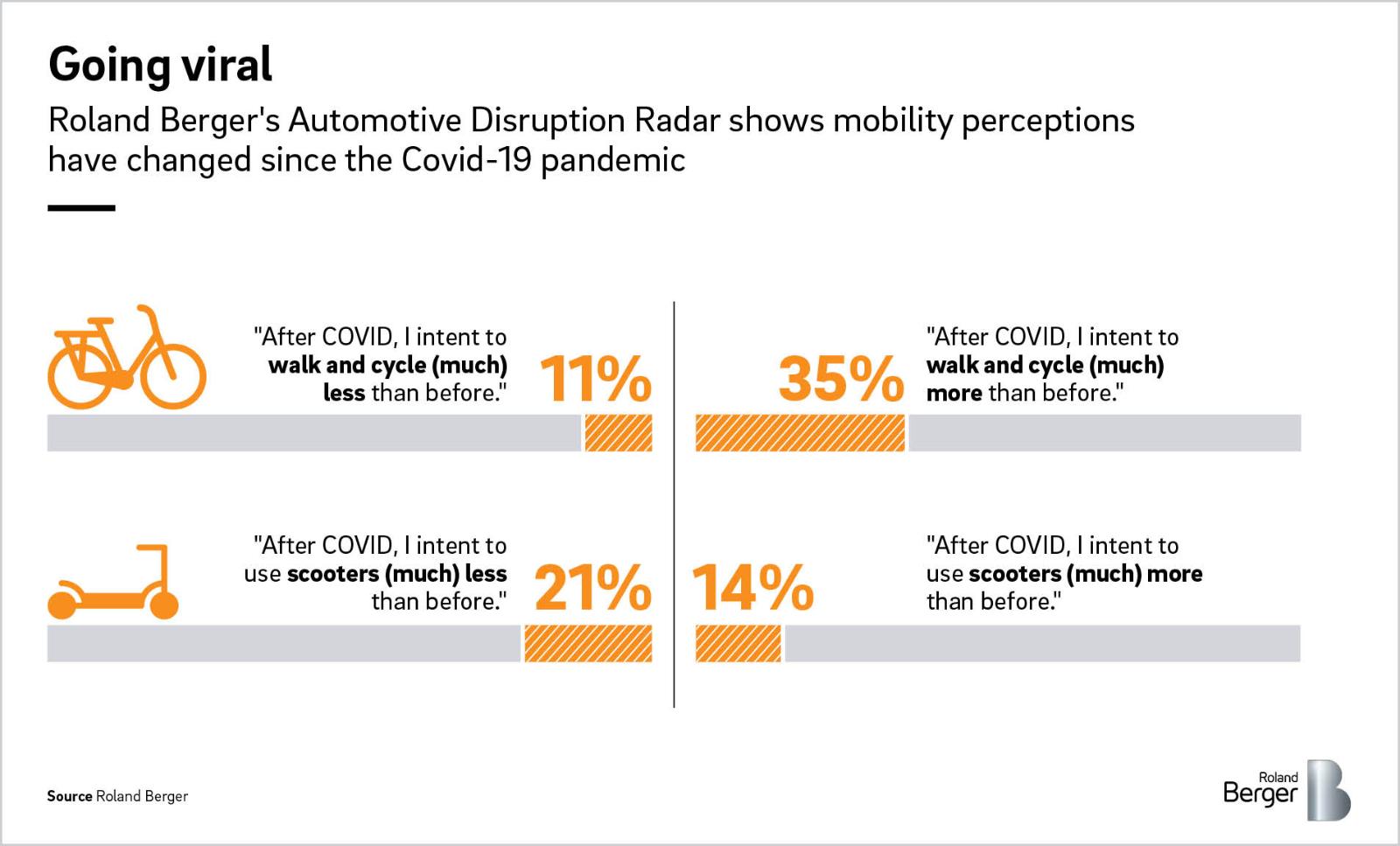

Just over three years ago, e-scooters were first used as rental vehicles in Santa Monica, California. Barely two and a half years later, in March 2020, more than 150,000 e-scooters were being used as rental vehicles in 177 cities in the US and Europe and around 20 million bicycles were in use. A success story with potential.

According to current estimates, the volume of rented bicycles totals USD 4 billion, and the e-scooter market is worth around USD 750 million. And the end of the road has not yet been reached: experts expect the volume of the e-scooter segment to be between USD 5 and 15 billion by 2025, while rental bicycles will range between USD 5 and 10 billion.

"The results show how micromobility is already improving urban mobility today"

Unlocking the full potential

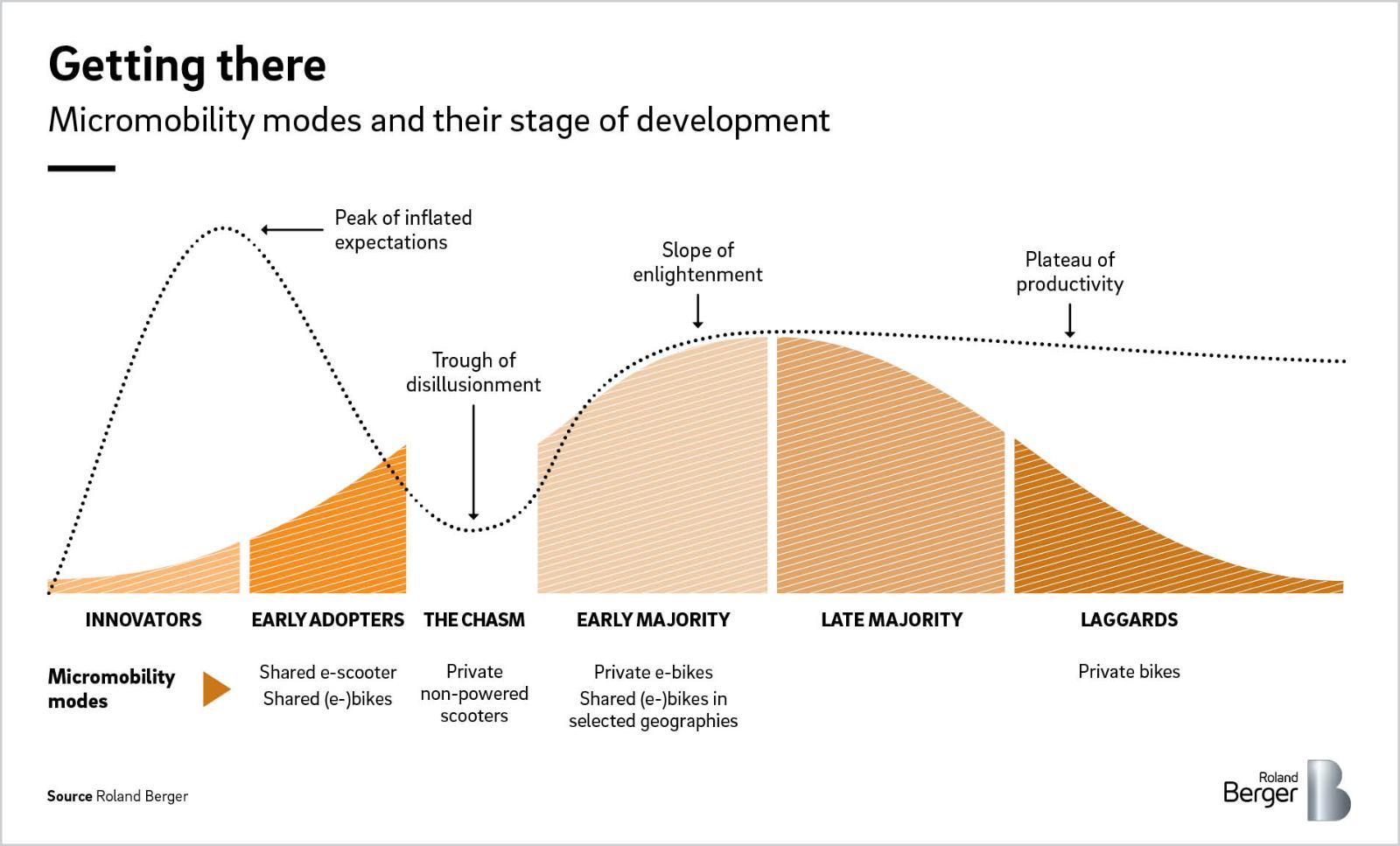

Nevertheless, the first hype seems to have subsided. After hipsters and early adopters triggered an unbelievable boom, management mistakes and ill-considered market entries of young providers led to massive reservations amongst the public. What is the next step?

"To get an idea of what a successful mix could look like, we examined use cases from cities and providers from all over the world," says Jan-Philipp Hasenberg, Partner at Roland Berger. "The results show how micromobility is already improving urban mobility today.

Four successful examples

Four successful examples show that micromobility can only develop its potential if the general conditions are right.

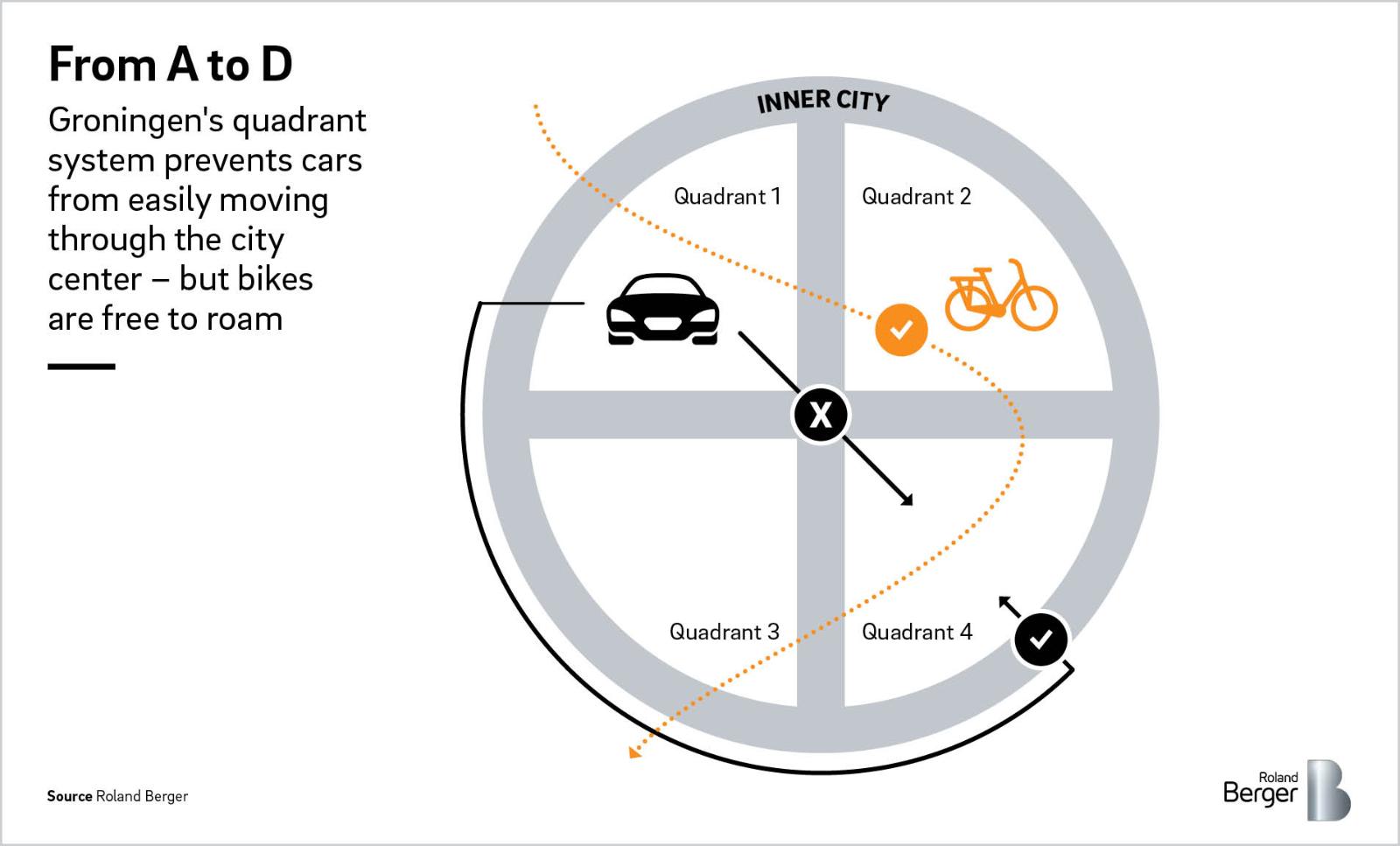

In Groningen, the city government already set the course for the bicycle in the late 1970s. The city center was divided into four equally sized segments and the traffic routing was made so unattractive for motorists that today there is hardly a car in the center. This meant that there was no need for a ban on car traffic at all, the number of cars fell by almost half.

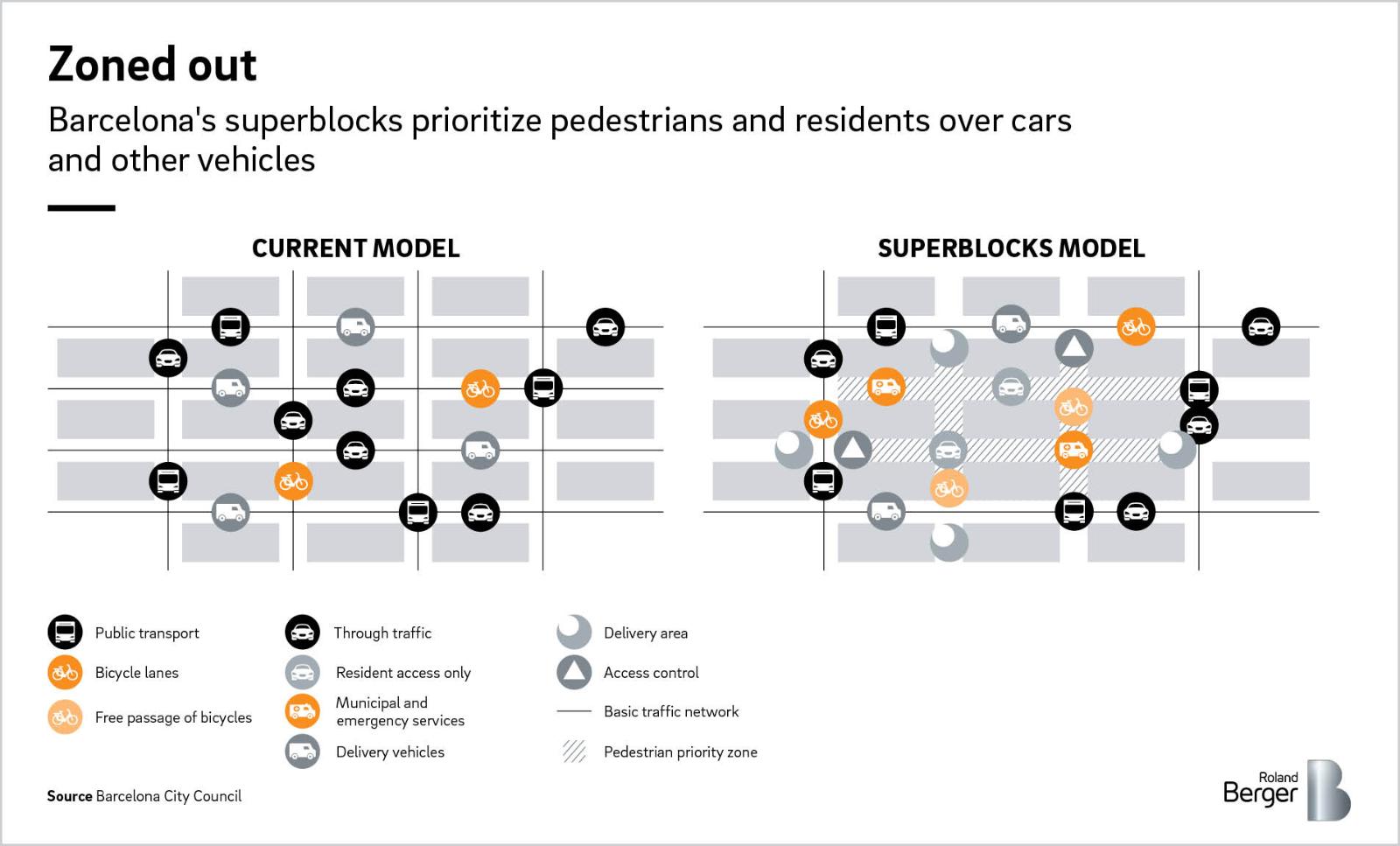

Barcelona is pursuing a similar approach with its strategy of "superblocks" or in Spanish "superilles". For this purpose, blocks of houses are combined into larger units, which may only be acccessed by cars in exceptional cases; traffic is consistently directed around these "islands". The blocks themselves are open to pedestrians and cyclists.

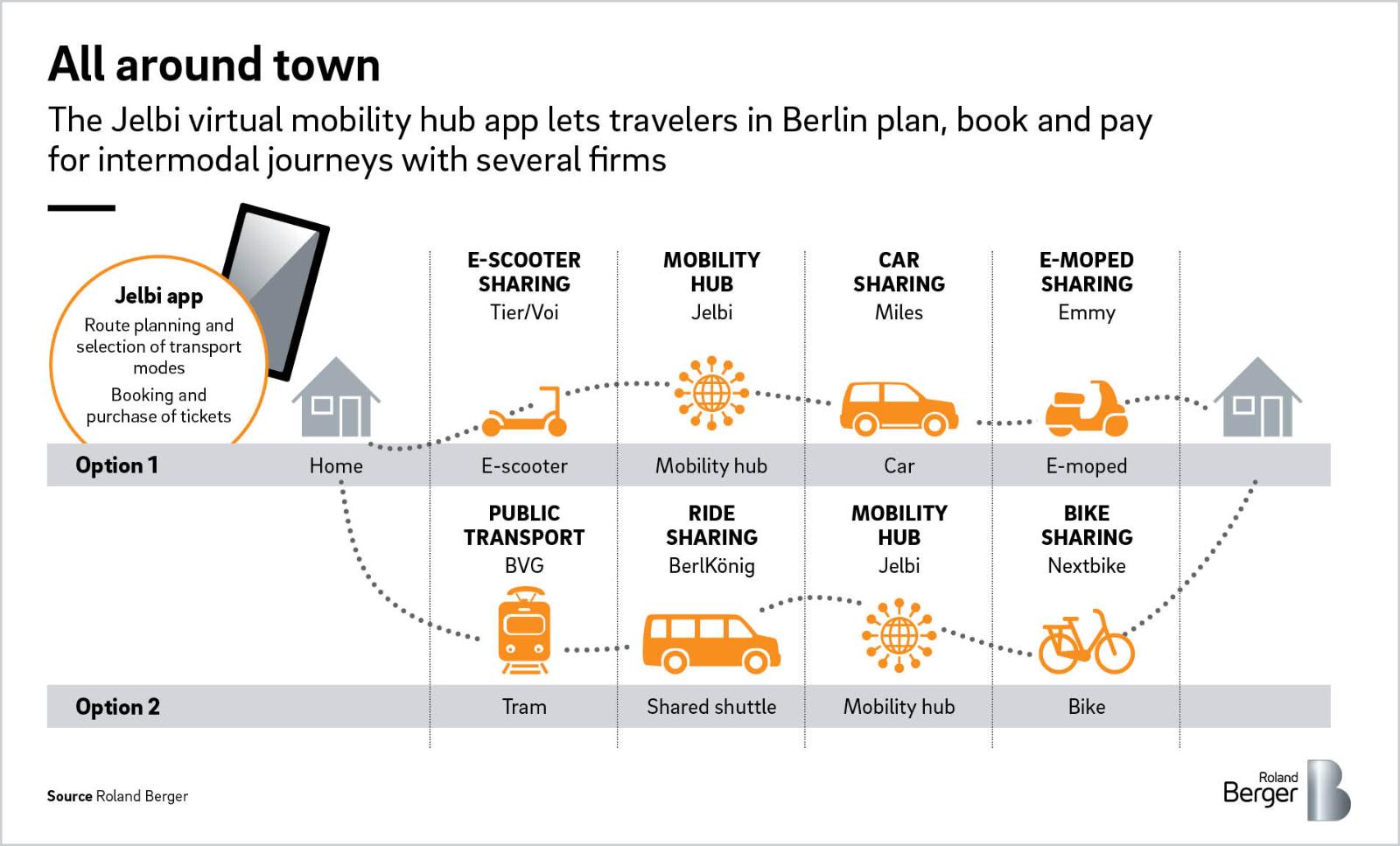

The Berlin App Jelbi, which was introduced by the Berlin public transport company Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe in 2019, shows how sharing schemes can be integrated digitally and meaningfully into an existing mobility network. The application allows users to plan and book public transport services in combination with shared mobility services and to switch intermodally to mobility hubs.

The fact that longer distances can also be covered by bicycle without any problems is demonstrated by Denmark, primarily by Copenhagen. In 2009, the local government launched the Cykelsuperstier. These are special superhighways for bikes with dedicated infrastructure linking the suburbs or the surrounding area with the city. Special feature: Here cyclists not only have space but also right of way at intersections.

Success story in the second rollout

The example of Paris shows that the hasty implementation of the new road users can also backfire. The city was flooded by a wave of e-scooters in the summer of 2018, after the city authorities released scooters amongst the traffic. Within a very short time, 20,000 e-scooters blocked the sidewalks. The population reacted with indignation to the reckless behavior of the users – and the rapid driving. The authorities successfully countered this by regulating the operation of e-scooters. Paris limited the number of providers to three and the absolute number of e-scooters to 15,000. In addition, 2,500 special parking spaces were created or designated, and a speed limit was introduced.

The example shows: Cooperation between providers and local authorities is essential for a successful rollout of shared mobility services . As obvious as the advantages of agile vehicles are – micromobility is not a sure-fire success.

The authors of the study have formulated seven success factors:

- Success factor 1: Develop of a safe bike lane network

- Success factor 2: Create more parking spaces for bicycles and scooters

- Success factor 3: Better connect micromobility modes with other transport types

- Success factor 4: Offer good suburban micromobility services to promote non-car commuting

- Success factor 5: Prevent or regulate car use in inner city and residential areas

- Success factor 6: Regulate shared micromobility providers to benefit city and users

- Success factor 7: Ensure provider business models and equipment meet customer/city needs

Register now to download the full study with best practice examples of micromobility and get regular insights into automotive topics.