Extensively reusing materials requires circular economies where the resource cycle is effectively managed, and incentives are aligned.

Closing the loop on the circular economy

Case studies and recommendations for achieving holistic circularity

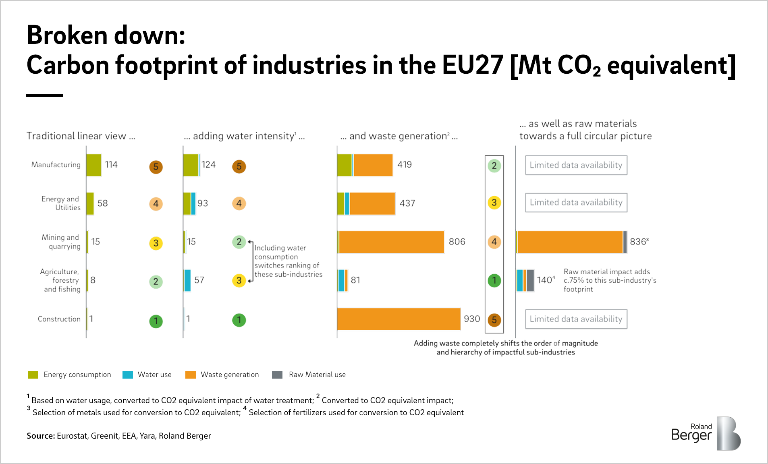

The traditional view on circularity has focused mainly on lowering energy consumption and emissions. But these are only a part of the story. Raw material use, waste generation and water usage must also be addressed to realize true circularity.

"Companies and governments both need to take action to accelerate the shift towards a holistic circular economy."

It is hard to imagine a world without waste. It’s even harder to imagine a world without waste where energy and resource use are far lower than today. Yet this is what the so-called circular economy aims for – the refurbishment of goods (from clothes to home furnitures or electronic devices) and recycling of materials (from plastics to aluminium or lithium) with zero waste, zero new extraction and zero carbon footprint. The question is, how do we get there?

Taking a step back: The traditional linear economy is straight forward. Virgin materials are turned into products for usage or consumption and then disposed of. But it is a highly resource-intensive model requiring significant energy, and often times water, to extract, process, use and then dispose of products that results into considerable wastage and emissions at each step of the value chain (see graphic 1).

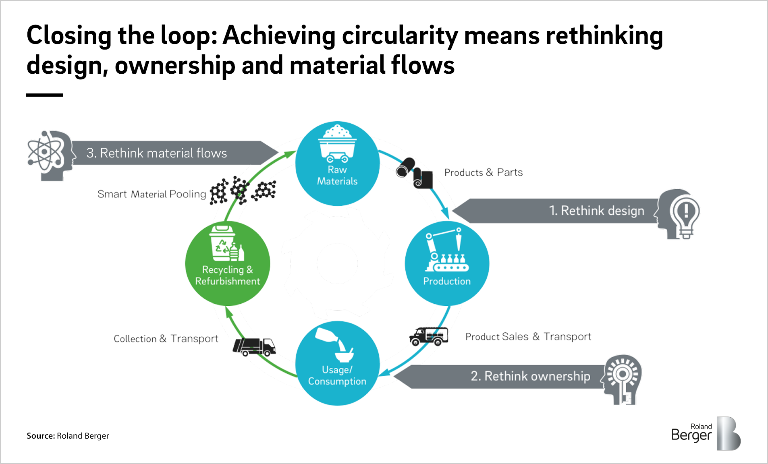

The idea of the circular economy is to close the loop in this cycle thereby removing the need to extract (or cut off) new virgin products. Instead of disposal, goods and materials are reused so the cycle can start with recycled or refurbished materials rather than virgin ones. Yet, by focusing on the reuse, the traditional focus has been set on decreasing energy consumption and driving down emissions as a key to its success.

But this isn’t the whole story. To achieve true circularity, raw material use, waste generation and water usage must also be factored in. There are two main reasons to include these dimensions into the circularity concept: water is arguably one of the scarcest resource and the most vital to human survival and extracting virgin material, treating water or waste are also energy-intensive activities that add to the total emission footprint that needs to be brought down to zero.

As a matter of fact, the use of virgin raw materials often goes hand in hand with technological evolution (for example, rare earth for batteries) which stresses the need for proper accounting. Regarding waste, a fully circular approach should encompass all outputs of industrial processes and systems, including waste streams linked to, for instance, by-products or scrap. Lastly, clean water, even at the less-purified levels tolerated by industrial applications, is increasingly scarce and requires energy-intensive treatment to make it circular.

To close the loop and achieve a truly holistic circularity, society must therefore rethink design, ownership and material flows. Many companies have already embarked on this journey.

Rethink design: Polyurethane recycling case study

Polyurethane items (for example, “foam” mattresses) can be recycled, but the traditional method of mechanical recycling recovers only low-quality PU with limited uses. Advanced recycling methods are therefore needed to close the loop. Thermo-chemical recycling is one option, but the high-pressure and/or temperature required to break down the PU into a useful industrial gas is too energy intensive to become truly circular. Chemical recycling, however, which decomposes waste PU into its base compounds so that they can be used like virgin PU, could soon be a viable circular option.

Rethink ownership: Redwood Materials case study

Redwood Materials, based in Nevada, USA, collects all types of electronic waste and removes batteries from it. The firm then recovers critical battery materials, such as lithium and nickel, and reintroduces these raw materials into the supply chain for reuse in the battery manufacturing process, thus cutting the use of raw materials. To date it has recycled the equivalent of 1 gigawatt hour of capacity, enough for 10,000 new Tesla cars.

Rethink material flows: Scrap aluminum case study

Production of primary aluminum requires a resource and energy-intensive process with a significant environmental impact. Fueling the process from mining of the ore bauxite to transporting the finished product to users produces 11.5 tons of CO2 per ton of aluminum, on average. But using scrap-based aluminum can cut this figure by 85-95%. For example, it avoids the electrolysis process, which accounts for more than half of primary aluminum’s energy consumption and carbon emissions.

What needs to be done?

Companies and governments both need to take action to accelerate the shift towards a holistic circular economy. From the business perspective, companies need to make the business case for the development of circular production models, invest in R&D to create sustainable substitutes and monitor and control material flows to eliminate excess waste. They also need to rethink consumption habits to cut waste, and support policymakers to develop policies relevant to current technologies.

As for governments, they must set holistic guidelines rather than specific, narrowly defined quotas or taxes. In this spirit, they must establish financial incentives promoting holistic circular production models (increase the true costs of virgin materials, introduce recycling objectives etc.). Finally, policy makers need to reward innovation and accelerate green start-ups, helping to create jobs and reducing the impact on the environment.

Such joint action is the only way to prioritize the shift to circularity and close the loop forever.