Thinking in decades

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta44_cover_download_preview.jpg)

The latest edition of Think:Act Magazine explores enduring business themes from past decades through a new lens of pertinence for the next 20 years.

by Stefan Stern

Photos by Michael Brennan

Staying engaged and flexible is key to navigating our era of polycrisis. The challenges can seem overwhelming, but one thing is increasingly clear: if we're going to make it out of these dark times, it will be a collaborative effort.

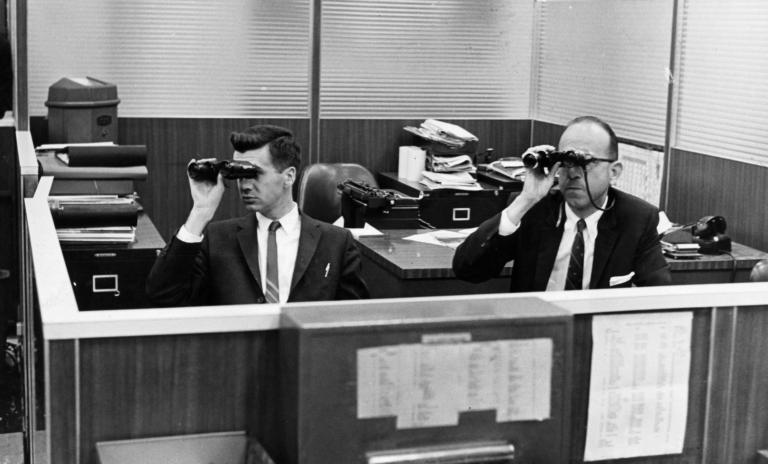

How do you know that your chief executive is not a deepfake clone? To be more precise: That WhatsApp message you just received from a strange but secretive source, followed by a voice note which sounded very much like your boss … can you believe it, or not? It is not a frivolous question. The Times reported this summer that "at least five FTSE 100 companies and one FTSE 250 company have been subject to impersonation attacks this year," and these are just the reported cases.

The real facts of business life are challenging enough without the virtual – and the fake – world providing more headaches for the C-suite. But at a time when we have learned to talk of the global "polycrisis" and the confusion it brings, it is not surprising if leaders are susceptible to being scammed as they seek inspiration from a variety of sources. "We are caught in a historical moment," says Gianpiero Petriglieri, associate professor of organisational behaviour at INSEAD. "Leaders risk being overwhelmed by the scale of the challenges," agrees Laura Empson, professor in the management of professional services firms at Bayes Business School, City, University of London.

One business book publisher recently sent this author a list of its new and forthcoming titles, and these included Toolkit for Turbulence, Adaptive Resilience, Strategy in the Age of Disruption and Leading with Vulnerability. Happy days are clearly not here again – yet. What is the nature of this leadership crisis, and how can we find a way through it? We face "complex situations in which there isn't an obvious answer or clear choice, and solving problems depends on the brainpower and engagement of everyone, not just the top leaders," as Herminia Ibarra, professor of organisational behavior at London Business School, has put it.

Ibarra argues that learning and adaptability are vital when there is so much uncertainty. She lists five critical leadership skills which she says will help organizations learn and adapt. See below:

This is a helpful checklist. And perhaps there are already some very good examples out there of managers and leaders doing the right thing and succeeding by it. In a series of recent blog posts for Forbes, the management writer Steve Denning has been arguing that some of the most prominent and successful names in business have been getting a few basic (and not mysterious) things right for some time. It starts with the familiar but too often neglected thought, popularized by the original and greatest management writer Peter Drucker, that businesses have one key goal or purpose: to find a customer and keep it. "The fastest-growing firms are no longer preoccupied with inert methods and processes, hierarchical control, outputs and profits – a way of managing that results in low capacity to adapt and innovate and low levels of staff engagement," he wrote recently. "The fastest-growing firms embody dynamic mindsets that lead to value creation, empowerment, collaborative networks and process-enabled outcomes, and faster growth. Power has shifted to customers who have new options and information about those options … So these firms recognize that they must understand and delight customers as a necessary prior step to making money, and must create new business models," he added.

A world facing a polycrisis needs collective leadership.

This much is clear. But carrying it out is not always straightforward. There are usually legacy issues of culture and practice to deal with; but also the classic dilemma of the "knowing-doing gap," as Stanford professors Bob Sutton and Jeff Pfeffer labeled it. And it is at this point that all eyes, both inside and outside the organization, turn to the leader and the question is asked: What are you going to do to fix our problems? Who is in charge around here? Perhaps this is not really a fair (or sensible) question. As Empson argues, the big problems we all face in business are "too complicated to be solved by individual leaders." A world facing a polycrisis needs collective leadership.

Empson has been studying professional service firms – lawyers, accountants, management consultants – for most of her academic career. It is here she has observed the potential benefits of shared and collective leadership, in contrast to the mythology and wishful thinking which lies behind the idea of the leader as a heroic soloist. "Collective leadership is an antidote to that [mythology]," she says. "We have always turned to 'heroic' leaders in times of crisis," she adds. This is where populism draws its strength. Populists "create a spurious sense of certainty," she adds. "But today at work we have a complex coalition of colleagues: nonhierarchical, multigenerational. This breaks down the old distinction between leaders and followers. It is a world where everyone – and no one – is a leader."

The post-pandemic world has also introduced an existential crisis in our relationship with work. But the current generation of leaders may struggle to answer these questions. According to Empson: "The future of work isn't out there, it has to be cocreated." And this is why leadership may start to look very different in a range of settings, she believes. "In a polycrisis you can't just drive into it in a conventional way. You need a multilayered and pluralistic approach. These problems are interconnected."

Lastly, what about women and leadership? wonders Empson. "They may have a different relationship with hierarchy. Women may respond to a lack of power by finding collective power." Empson has support from elsewhere in academia. Archie Brown, emeritus professor of politics at Oxford University, made some similar arguments in his 2014 book The Myth of the Strong Leader. He too favors what he calls "collegial leadership" over those who "dominate colleagues and concentrate decision-making in their own hands."

So, how else can we be certain that the boss is not a deepfake, or a robot? Clearly, they need to pass a human being test. Gianpiero Petriglieri's latest work, set out in a 15-minute YouTube talk, discusses "leadership as a kind of love." That's right: love. Petriglieri makes a beautifully simple point. He says that, if you want your people to move (to change, to act differently), then they have to be moved – emotionally. Robots and deepfakes can't do this. Leaders will have to show some humanity if they want a human response. "I am trying to reconcile people with their experience," he explains. "So much of our writing – academic or practitioner – really divorces leadership from people's daily experience. It dehumanizes it, either making it too virtuous, too pure, or too mechanical. So the leader either becomes this kind of saint, an anointed person, purposeful and values-based, or this kind of Machiavellian mechanic."

How do his students and executive clients react when he talks about leadership as a kind of love? "People respond in a very interesting way," he says. "Most people tell me – 'oh my God, that is so interesting and so refreshing, and I completely endorse that, but I bet you have lots of people who find it strange.' So they always project the foreignness of this idea onto someone else. 'I would like it, but I can't …' But to say that leadership is a kind of love does not mean that leadership is good. There is a range. The worst kind of love is narcissistic. 'I don't actually love you, I love myself in your presence.' Love can be a kind of language that is used to justify your views. Abusive leadership can be like this. The most common experience is of mediocre love: 'I love you, but I'm afraid of that, and so I will try to control you.' The leadership is diminished by the impossibility of letting go of control. The best kind of love is the most difficult: How do I really see you? How do I set you free? I think leadership has that range. It can be abusive – or at least constraining. At its best it can be liberating. And when I qualify it in that way, many people go 'oh, yes.'"

The metaphor works. Charismatic leaders perform a kind of seduction. But then what? "The arc of the charismatic leader is always an impossible ascent and an inevitable disappointment," Petriglieri says. "That's because the seduction is so intense, and then there is no way it can deliver. Everyone is into ‘passion'! But passion has to evolve into something more stable and reliable. "Indiscriminate seduction, which stops, is the mark of the insecure character. Leadership theory caters to that insecure masculinity which actually becomes toxic. It seduces but then doesn't know what to do next."

Every era has its own idea of how to run a company.

Taylorism

Frederick Winslow Taylor published The Principles of Scientific Management in 1909, codifying his belief in efficiency at work. Taylorism may have been well intentioned but can justify harsh and inhuman practices.

MBO

Management by Objectives was an idea developed by Peter Drucker in 1954. It had a plausible common-sense factor: keep objectives in mind. The difficulty came when objectives were in conflict, or became too rigid.

TQM

Total Quality Management was developed by US business guru W. Edwards Deming, but perfected in post-war Japan. Again, what started off as a good idea became distorted, causing a loss of faith in the very idea of "quality."

BPR

Business Process Reengineering was seen as a panacea for a recessionary 1980s world. The book Reengineering the Corporation by Michael Hammer and James Champy advocated radical surgery, which sometimes paid off – but also left some corporate patients in a worse state.

Agile

Emerging from the high-tech world, agile has been held up as an answer to the corporation’s problems. But it is not for everyone. The principles – of being responsive to customer demand – are good.

"Two things need to happen: Shit has to get done, and people have to be held together and moved."

Petriglieri's discourse about love surrounds humanizing leadership. "Our theories and especially our practices are still attached to a metaphor of machinery," he explains. "The love metaphor is a way to get away from the mechanistic. I do this in class – I say: If you thought about love what would you worry about? Am I loving the right people or am I wasting my time? Am I really caring? Do I get love back? Do I get hurt? People respond because it gives them a lens. Two things need to happen for any organization to exist. Shit has to get done, and people have to be held together and moved."

And of course, love provides armor against AI, robots and algorithms. "Algorithms are Taylorist wet dreams," Petriglieri says. It's digital indoctrination … the Taylorist dream can be realized. "To me love is the antidote to that. The best kind of love is an investment. And it's a liberation. It's the opposite of an indoctrination." The way through our current troubles, then, will involve collective leadership, adaptability and a human response. We should not be shy about that. As the poet W.H. Auden once wrote: "We must love one another or die."

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta44_cover_download_preview.jpg)

The latest edition of Think:Act Magazine explores enduring business themes from past decades through a new lens of pertinence for the next 20 years.