Your path to tomorrow, today

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/tam_future_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

The actions of the present lay the foundations for the future. What does this saying mean in turbulent times? Consider a mix of solidity and flexibility!

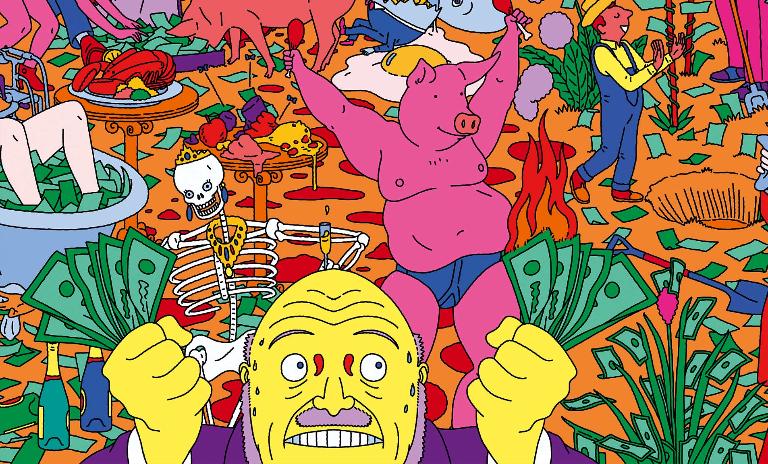

The pressure to report profits on a quarterly basis has driven some organizations to lose sight of the bigger picture. But as the long game's list of increasingly vocal supporters are quick to point out, defining the future of stable growth has never been more important.

Quarterly capitalism, the term given to publicly traded businesses that have to publish performance data every three months, has become increasingly unpopular in recent years. The problem, its detractors say, is that it skews strategies in favor of quick wins and away from healthy, sustainable growth via projects that deliver strong ROI over time. At its worst, it encourages criminal behavior like that exhibited in Enron’s collapse and the casino-economics that caused the financial crisis of 2008-09. During a 2015 speech while on the US presidential campaign trail, Hillary Clinton risked the ire of institutions: "Quarterly capitalism as developed over recent decades is neither legally required or economically sound. It’s bad for business, bad for wages and bad for our economy," she said. Oddly, her rival, the cutthroat capitalist Donald Trump, broadly agreed with this assessment. A year after winning the race for the White House, he met with global CEOs to discuss reducing reporting requirements on US companies from four to two occasions each year.

There is nothing innately wrong with thinking short term. The problems arise when pressure from investors prejudices companies towards a fast buck. "If you’re pressed to forgo longer-term investment then you might be fine for the next couple of years, but in five or 10 [years] you're gone. That's the downside of short-termism," explains Mike Useem , a management professor at the Wharton School of Business. "Long-term change is part and parcel of what it means to grow. Take ride-sharing: Uber and Lyft lose a lot of money, but you only have to look at their share price to see that short-term loss is what it took to become the dominant players." At the time of writing, Lyft has a market cap of nearly $21 billion, while Uber had just gone public at a valuation of $76.5 billion, this despite losing $911 million and $1.8 billion respectively in 2018.

"There is nothing innately wrong with thinking short term. The problems arise when pressure from investors prejudices companies towards a fast buck."

Investors keep backing loss-making companies like these because the eventual prize is potentially enormous. Despite his serial success as an entrepreneur, Little Dish and the New Covent Garden Soup Co. founder John Stapleton's strategy has been to exit in trade sales pre-IPO. By not taking companies public, he enjoys more control over brands’ long-term plans. He says short-termism robs businesses of the freedom to fail on a case-by-case basis. "When you make a mistake, it teaches you a lot about sector forces and the customer base," he says. "Success, on the other hand, is a lousy teacher. If you trip up a few times you get a very clear understanding of what success looks like as a conglomeration of different factors. To get a really big win, you need to establish a vision and develop opportunities, create an understanding of your consumer and generate traction. That’s not going to happen in three or six months, or even a year," he adds.

Perhaps the most famous champion of the long game is former Unilever boss Paul Polman. He ended quarterly reporting to FTSE shareholders on his first day as CEO in 2009, saying: "Unilever has been around for 100-plus years. We want to be around for several hundred more … if you buy into this long-term value-creation model, which is equitable, which is shared, which is sustainable, then come and invest with us. If you don’t buy into this … don't put your money in our company." Along with anecdotal evidence like this, the numbers suggest the tide is slowly turning against quarterly capitalism: FTSE-listed businesses issuing quarterly reports dropped from 70 to 57 between October 2016 and August 2017. As for the wider FTSE 250, only about a third were taking part in the exercise.

But is there enough evidence that short-termism truncates economies and robs enterprises of their potential? Two things need to be proven: that investors prefer quick wins over sustained growth and that this acts as a brake on investment. The evidence is inconclusive. In a paper for Harvard Business Review entitled "Investor Short-Termism: Really A Shackle?", professors Rebecca Henderson and Clayton Rose concluded: "The presence of most types of institutional investors among a company’s shareholders appears to have encouraged a long-term perspective, rather than retarded it, and has sometimes provided managements with 'air-cover' to stay the longer-term course during difficult periods." Then there is a study by a group of US-based economists linked to the Federal Reserve, which found that listed companies invested nearly 50% more in research and development than private ones, according to their corporate tax receipts. It also found that companies upped their R&D game post-listing. On average, the ratio of their R&D spend compared with physical assets increased more than a third. So, given this, why is there such a strong association between quarterly reporting and short-termism? For one thing, the US study is quantitative, not qualitative, meaning it doesn't shed light on what companies are spending on. Plus, it doesn't account for non-R&D short-term plays that could hurt company fortunes, such as ill-thought-out acquisitions and environmental damage.

Another reason, according to Useem, is that big institutional investors including BlackRock, Fidelity and Vanguard have publicly backed the campaign against short-termism. At the end of 2018, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink wrote a letter to CEOs containing the line: "Commitment to a long-term approach is more important than ever – the global landscape is increasingly fragile and, as a result, susceptible to short-term behavior by corporations and governments alike." But the pressure for results remains, whether it's perceived or real, and it is responsible for corporate collapses from Enron to Lehman.

How then, can companies resist the pressures and aim for sustainable growth? John Stapleton believes there is no need for radical, structural change, but that with clear communication CEOs can shift investors to their vision. If you state your intentions and illustrate the benefits, regularly feeding back to investors to explain your actions, then bosses will discover most investors have patience. "A CEO who exhibits the courage of their convictions, who makes promises to shareholders which are kept, will get a warm reception the next time they make a statement. There will be greater belief in the business."

Technology could also have a role in changing perceptions. Chris Ganje, the CEO of tech company Amplyfi, says that plotting long term will be more powerful because artificial intelligence has increased opportunities for trend identification. His company has developed a business intelligence tool which analyzes data across academic papers, government reports, databases, journals and news items, giving decision-makers rich information and therefore enabling them to spot trends and communicate evidence to shareholders. "Recent innovations in AI and data harvesting mean businesses can plan not just in months and years, but in generations. The limits of human imagination have been overcome by machine learning, which is able to make connections and identify trends beyond the capabilities of human researchers and analysts," he says.

A last remedy to short-termism rests in the career arc of CEOs, whose average tenancy in the US is around eight years, according to Useem. At the start of this period R&D spend increases, but towards the end it cuts back "not hugely but perceptibly" as bosses try to carve out their legacy before they depart or retire. "It's no surprise that, unconsciously or not, CEOs at the end of their term consider that they won’t be around forever, so they spend on things that have more immediate benefit to them," he says. "It's one of the curiosities of the corporate condition: We ought to be Adam Smithian rational calculators, but our own career often kind of gets in the way."

Whether caused by shareholders, by personal ambition or by something else, short-term strategies represent a missed opportunity for businesses to establish sustained growth and, potentially, bigger profits. And if Donald Trump, the king of the quick win, thinks so, then who would disagree?

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/tam_future_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

The actions of the present lay the foundations for the future. What does this saying mean in turbulent times? Consider a mix of solidity and flexibility!

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.