The purpose principle

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/think_act_magazine_purpose_the_purpose_principle_cover_1_download_preview.png)

What does purpose mean to you and your business? Our Think:Act magazine on purpose addresses changing values in the business world.

by Bennett Voyles

Read more about the topic

"The purpose principle – missions give businesses strength"

What does it take to build an iconic company? If you ask influential author, researcher and advisor Jim Collins, superior results are the product of asking exactly what it is you have to offer.

The value of institutional purpose is a relatively new discovery for many organizations, but not for celebrated author Jim Collins. For the writer of such influential business books as the groundbreaking "Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies" (co-authored with Stanford professor Jerry Porras), and "Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap ... and Others Don't", one essential quality that important and enduring companies share is having a sense of meaning that goes beyond simply keeping their stockholders happy. In a telephone interview from his home in Colorado, he talked to Think:Act about his evolving view of purpose and what it means.

How important is purpose if you want to build a great organization?

One of the key qualities of an enduring company is that the founders instilled a sense of being there to serve a purpose that's larger than any of us. Purpose tends to be found fairly early. Back in the 1970s at Apple, for instance, Steve Jobs was able to articulate the idea of "hey, what this is really about is building bicycles for the mind. Our purpose is to think about the world and say: 'What will change the world more – making one computer a thousand times larger, or making a smaller computer and putting it in the hands of a thousand creative people and letting it bloom?'"

A good purpose sticks: When Jobs came back to Apple in 1997, one of the first things he did was find the people who still shared that ideal. It was still there, in the woodwork

What if you've never had a clear purpose?

That's much harder. In that case, you have to ask: "Why is the work important in the world?" Then you start working backwards: "Why is it important that we make semiconductors?" And you begin to unlayer those reasons. If you're actually doing something effective, there will be a reason you can put your finger on. But it's a lot harder to find if you didn't instill it from the beginning.

But purposes don't look alike. If you look at the examples of purpose listed in "Built to Last" and compare Nike's to Disney's, 3M's, Patagonia's or Pacific Theaters', you'll find that they're really different flavors. Some are really competitive, some are really creative, some are really built around social change and some have to do with serving the people who work for you. If your purpose really is just "we love to win," that's okay. If your purpose is "we just love to create things," that's okay. If your purpose is "I really want my people to flourish," that's okay. What matters is if it is authentic. An inauthentic purpose is worse than having no purpose. Even if it's a commendable idea, purpose can't be a bolt-on. It can't be something that you do to feel good. It has to grow from the actual work.

"Purpose can't be a bolt-on. It can't be something that you do to feel good. It has to grow from the actual work."

In "Built to Last", you quote the historian Barbara Tuchman on the tendency of "affluence to smother motive." Do today's cash-rich companies face any special risks?

Interestingly, great companies don't usually fail because they become complacent, but because they pursue undisciplined growth – growth that doesn't fit with the purpose of the company, that doesn't fit with why it could be best in the world, that is just fueled by big acquisitions. The hubris born of success leads to what we call the undisciplined pursuit of more.

This is why having a purpose and a drive far beyond the purpose of making money is so important. Because if your purpose really is just to make a lot of money, then when you have a lot of money, you run out of purpose. But if your purpose is to do amazing things or create things, you'll never run out of purpose because you're never done.

When you study the people who built lasting, iconic and visionary companies, the drive that they had was an inner compulsion. It had nothing to do with their circumstance. It's like trying to imagine Beethoven after the success of the Fifth and Sixth Symphony saying, "I have too much cash. I think I'll skip writing the Seventh or Ninth and take it easy now." He couldn't help himself.

So pay doesn't matter?

You can't turn the wrong people into the right people with incentives. If you have the right people, they're going to try to do the right things, and if you have the wrong people, it doesn't matter. Great vision without great people is irrelevant.

You should be very careful with incentives. The economic evidence is clear: Incentives will affect behavior. If you have incentives that drive you towards undisciplined growth, you're going to get undisciplined growth.

Discipline, on the other hand …?

One of the real differentiators of companies that endure at a really high level is that they're even more disciplined in good times than in bad times, because it's what you do before the storm comes that most determines how you will do when the storm arrives. You don't grow too fast. You put reserves away for when the bad things come. You don't compromise on the quality of people you hire. You don't get sloppy around the edges because you can. Then, when the storms finally come, you are the one that pulls ahead.

A former Stanford Graduate School of Business professor, Jim Collins founded his own "management laboratory" in Boulder, Colorado in 1995 and has authored or coauthored six books that delve into what makes companies great. He was named one of the 100 Greatest Living Business Minds by Forbes in 2017.

Several years ago, you served an appointment on leadership at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Did that change any of your thinking about discipline or purpose?

Let me ask you: Which is a harder life? Being a West Point cadet, where you have four years of academic burdens, physical burdens, leadership burdens, military training burdens and at the end you are also signed up for a minimum five years of service and you're going to be charged with responsibility for people's lives and the accomplishment of missions? Or being a Stanford MBA student hanging out in Silicon Valley ready to go do a startup? Yet my West Point cadets struck me as a happier bunch than my Stanford MBA students by a sizeable delta.

Why do you think that was the case?

A lot of it came down to their sense of purpose. Ask the Stanford MBAs: "What cause do you serve? What are you doing that you might be willing to suffer and sacrifice for? Why are you here?" Very few of them would have an answer. At West Point, you get an answer. The sense of service is there from the get-go.

There were a couple of other things. Ask West Point cadets: "How many of you have experienced failure and inadequacy here?" They will all raise their hands because the system is designed to make sure you struggle and fail. You learn that the only way you really do well is to help each other. At West Point, the opposite of success is not failure, but growth. And success is always communal – you only succeed by helping each other succeed. What could be a happier situation?

The great companies you've written about often did most of their work in-house – you've written that Disney didn't even outsource parking. Can strong organizations still be built today in our world of extended supply chains?

The nature of supply chains today clearly means that there's going to be a lot of moving parts, including outsourced parts. Maybe it's like being allied forces – we're all coming from different countries that need to stay relatively unified in pursuit of an overall mission.

My mentor Peter Drucker made an interesting observation that was profoundly right for the 20th century: The alternative to tyranny was well managed organizations, widely distributed. Without them, tyranny wins. Today, I believe we might be on the cusp of a shift. If the 20th century was about organizations well managed, the 21st century might well be about networks well led.

You've always advocated the pursuit of what you call the BHAG (Big Hairy Audacious Goal). Now that you've just turned 60, do you find that your sense of purpose has changed?

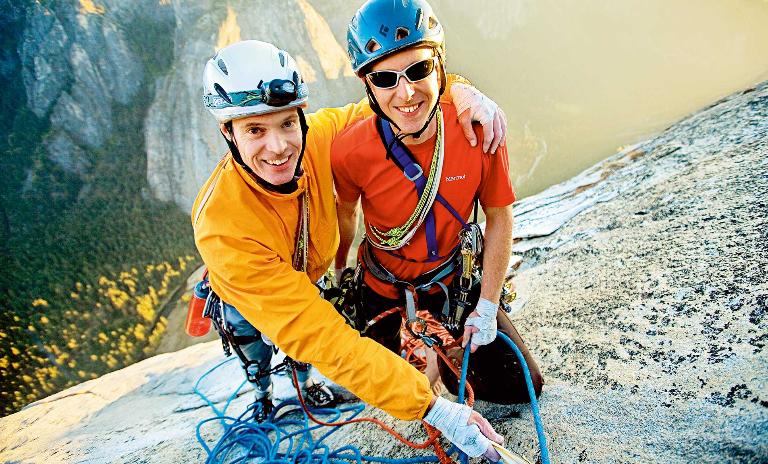

Yes, and I think rock climbing might be a good illustration of how. Rock climbing has always been a central theme in my life, this unifying theme of growth and adventure and the pursuit of big hairy audacious goals, but my sense of the purpose of climbing has changed over the years – or maybe I've uncovered a deeper purpose. When I was younger, climbing was really about how to persist through cumulative failure. One route took me five years to do 25 moves. I basically failed for five years before I finally succeeded. Part of climbing was to learn how to go through that process and to eventually accomplish the goal.

Now climbing is about enjoying a great time with great partners. Whereas I used to ask myself what climb I wanted to go do, now I ask who I want to do the climb with. The climb becomes almost just a canvas for enjoying a marvelous shared day of adventure, comradeship and friendship, of watching out for each other and having a great conversation on a belay ledge a thousand feet above the ground while the birds fly by and then summiting the climb. In almost every aspect of life, I keep coming back to the idea that the who is ultimately more important than the what. The climb doesn't care if you get up it. Your friends care, and you care about your friends.

I've also been thinking a lot about what I want my life's work to be. I have a picture of all of Peter Drucker's books from a shelf at the Drucker Institute set up in chronological order. At my age, Peter was only about 25% of the way through his life's work. I've been doing a lot of thinking about how to make good on that idea, not just the numbers, but finding an overarching theme. If you look at Peter's shelf and you were to ask yourself what the overarching question is, I think management was a sub-point. The deeper question is: "How do we make society both more productive and more humane?" That's a beautiful, marvelous question that runs through the 30-odd books like a common thread. A lot of what I've been thinking about is that I've been really fortunate to create a body of work up to this point, but how can I tie it all together? What would my question be?

Jim Collins believes that the key to enduring success lies in understanding how you can be most useful.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/think_act_magazine_purpose_the_purpose_principle_cover_1_download_preview.png)

What does purpose mean to you and your business? Our Think:Act magazine on purpose addresses changing values in the business world.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.