How robust is your company?

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/TA31_Cover_EN_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act Magazine explores how today’s companies can become robust and survive the coming decade through lessons in innovation, purpose and adaptation.

by Detlef Gürtler

illustrations by Matthias Seifarth

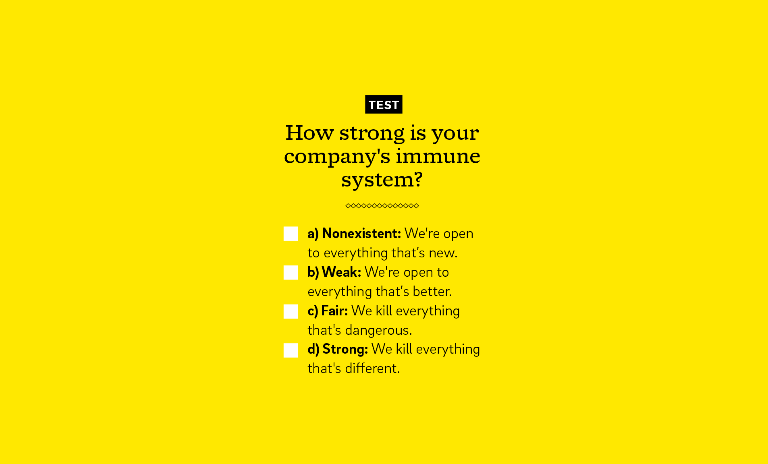

Unpredictable events can upend your business at any moment. But you can protect yourself from the changes ahead by assessing your company's ability to fight off threats – whatever form they take. We have constructed a series of short assessments and questions for you to see whether you have what you need to come through the 2020s. Test your strength…

No matter what box you checked, it's highly probable that your company's situation would be best described by D. Otherwise you wouldn't be answering this question in the first place. A strong immune system response against anything that might be harmful has been seen as a vital ingredient for survival by every institution.

Oh, and it's not just one ingredient. It's more like a handful of them, all of which join forces to keep everything out that might be harmful, dangerous – or just plain strange – for the institution. Take the immune forces of the human body as an example: There are leukocytes and phagocytes, granulocytes, antibodies, antimicrobial peptides and enzymes, B-cells, T-cells, killer cells, to name just a few of the players in the immune system.

And what about your company? Are there guards and firewalls, and then keys and codes, closed shop mentalities and the notorious not-invented here syndrome? And those are just the tip of the iceberg. If you're in a good mood, you could call it your corporate culture or "our DNA." If you're less well-disposed, you might call it your "bullshit castle" – which is the nickname that the former DaimlerChrysler CEO and charismatic leader Jürgen Schrempp gave to his corporate headquarters in Stuttgart before he broke the bureaucracy apart to let new ideas flourish. But no matter what you call it, this immune system is here to stay – simply because that's how human beings and corporations survive. So, congratulations: Your company is able to do business. Well, business as usual, that is.

3,000 is the number of employees at DaimlerChrysler's Stuttgart HQ when CEO Jürgen Schrempp called it "Bullshit Castle" two decades ago, half as many as worked there in 2019.

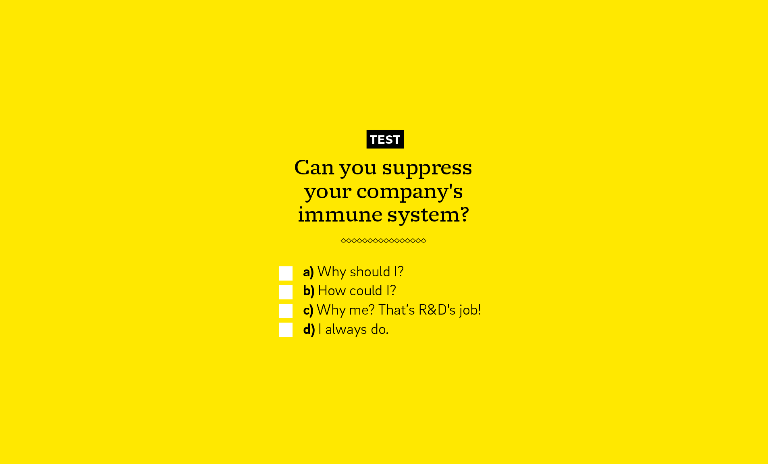

Yes. Yes, it's true: We just said that the corporate immune system is here to stay, because otherwise your company – just like a human being – might not survive. But, once again – as with a human being – there are situations where your survival depends on the suppression of your immune system. This happens when something new, something really different is desperately needed. Think, for example, of an organ transplant. In most of the cases, the immune system would bluntly reject the transplanted organ: "Hey, you're strange, you're different, get out of here!" In medicine, immunosuppressive drugs are used for this purpose. Success is not guaranteed, but without those drugs, failure is inevitable.

This kind of exceptional situation also occurs in business. One of these business-as-unusual cases are mergers, where the two different corporate cultures should not collide and crash, but should merge as well. Another, more frequent case is that of innovations that could be steamrolled by the dominant forces inside the company. Sure, this rejection may endanger the long-term survival of the whole company, but, let's face it, that's how an immune system works. So it's your job to find and use the right immunosuppressive tools. One of those tools has already become quite famous: the speedboat solution. Keep your most disruptive innovations out of the tanker-like corporate structure and place it on a speedboat instead. Once it has gained traction and size, it can join forces with the tanker, without the risk of being destroyed in the process. That's how Nestlé nurtured its Nespresso brand – far away from its mainstream coffee business.

We especially like another tool recommended by the Swiss business theorist and innovation expert Alex Osterwalder. He proposes a "chief internal ambassador" to build bridges between corporates and innovators. This ambassador should be experienced enough to know your company's immune system. And he or she should be open enough to understand what the innovators are doing and how this might change the company's product range and/or business model.

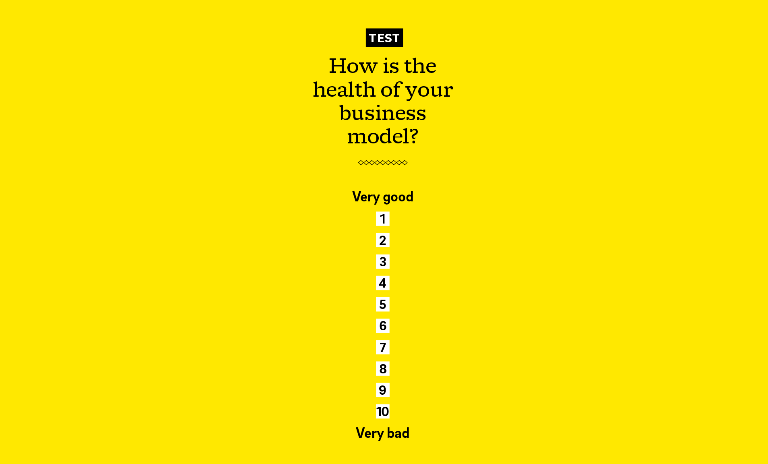

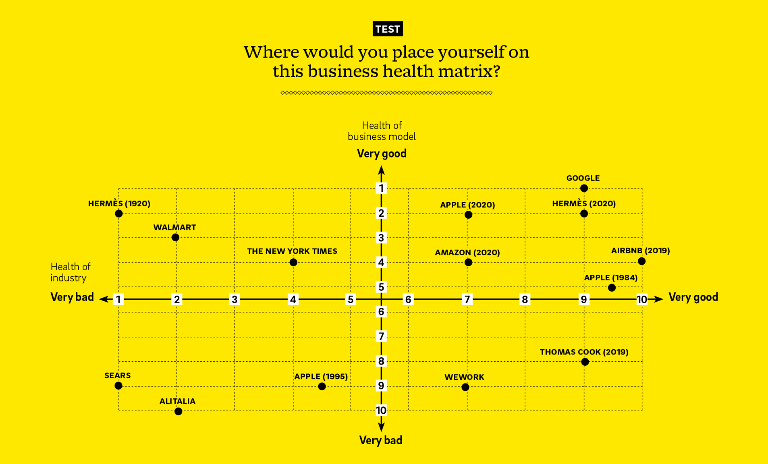

For most managers, the industry that they're in is their main concern: volume (and growth rate), margins, competitors and the business environment. So the health question should be easy to answer. And that's part of the problem. Because the better its shape, the more attractive it is for disruptors. Take for example one industry that until 2020 had grown tremendously for decades: tourism. One of its global market leaders, Thomas Cook, went bankrupt in 2019. Not because the industry was weak, quite the contrary: A bunch of new competitors like Airbnb or Booking.com had conquered huge chunks of the market – and they did it by offering products and services that the incumbent giant had neglected to provide.

On the other hand, if the industry you're in is in bad health, that needn't be true for your company as well. In fact, it could just as well be an incentive to revisit your business model and outpace the others. One day this story may be told about one of today's tourism brands, but, well, right now there's too much disruption work in progress to see who will make it.

So let's dive into history instead; let's have a look at a really extreme example of an industry that was already doomed over a century ago: saddlery and harnesses. No one needed horses and carriages anymore; first the train and then the car took over the horse's function in passenger and cargo transport. What could you gain in outpacing the competitors in the dying saddlery industry? The answer can be found in Paris at 24 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, the headquarters of one of those saddleries – Hermès – for more than 100 years. The Hermès family had seen that their core strength was not the production of saddles and harnesses, but serving the fashion needs of the global elite.

Similar stories are now being written in more contemporary doomed industries. For example, The New York Times is proving to be quite successful in expanding their quality journalism brand beyond the struggling newspaper business even though the rest of the industry is in doldrums. The New York Times management identified quite early that its core strength was not about spreading ink on paper, but about telling great stories in a great way – a business model that is at least as old as Homer. So, no matter what the state of your industry, it's your business model that should make the difference.

5.3 million is the total number of New York Times subscriptions at the end of 2019, of which just 850,000 are for the print edition.

What did you consider when you answered this question? Being the good manager that you are, you surely did not only think of revenues, profits and margins, but also of defensibility: How high is the wall, how deep is the moat that surrounds your business model castle? And hopefully you did not only consider your defense against today's competitors, but also against tomorrow's disruptors. Some of them may be high and mighty like Apple – the road to Apple's success is paved with the corpses of not just companies, but also entire industries. Some of them may be small and dirty like Napster – the completely illegal file-sharing service that changed the face of the global music industry.

But there's one more thing you might not have considered in your answer: expandability. If your business model is as good as you think it is – what about giving it a shot in another industry? Or even in many other industries? Hermès did it: They transferred their business model (highest quality for global elites) from saddles to handbags and from leather to silk. Apple did it: They transferred their business model (tech design for the rest of us) from computers to phones, accessories and services. So why shouldn't you do it, too?

15% is the percentage growth of Hermès' 2019 revenue when compared with the prior year.

With the two marks that you made for test three and test four you should be able to plot yourself and your organization in our handy business health matrix. So that you can look over your shoulder at how you are doing, we have placed a few other companies there too. So how are you doing when you compare yourself to Apple or Hermès? And does the health matrix inspire you to make sure that you are fighting fit, no matter what the world might throw at you?

$2.3 billion is the figure by which Apple exceeded its Q1 2020 projected revenue: $89.5 billion.

If your answer is 10% or less, then your company is in great danger of going out of business. Of course you need – and surely have – people below the CEO that are focused 100% on innovation, but without a strong commitment from the CEO innovation will simply not get traction. Business theorist Alex Osterwalder even recommends that CEOs should spend 40% or more of their time on innovation matters.

Well, one of the privileges you usually have at the C-level is that you don't have to calculate what percent of your workload is spent on which matter. And you should not start doing those kinds of calculations just to prove that you are committed to innovation. This is not about checking a box for a shiny corporate innovation report. So you may choose another KPI (key performance indicator) for bringing innovation to power, as proposed by Osterwalder: Innovation should be discussed weekly at the CEO level. Otherwise, your claims of focus on innovation are just for show – or what you might call "innovation theater."

Sure, you have a vision, and a mission, and objectives, and directives. They keep you afloat. But a soul keeps you alive. The best example we can think of is the Starbucks revival. Back in 2007, seven years after he had stepped back as Starbucks' CEO, Howard Schultz noticed that the company was not only losing steam and profitability, but was about to lose its soul. He noticed that when he entered a Starbucks café and ordered a coffee, he couldn't see how his coffee was made. Due to the expansion of the business, the Starbucks management had introduced new, more productive coffee machines. But these machines were so big that the customers could no longer see the baristas doing their job. For Schultz, the sensual link between coffee and customer was indispensable. It was the reason why he had joined Starbucks: On a trip to Italy he was fascinated by the elegance and efficiency of a barista, and he wanted his customers to experience the same fascination. After his return as CEO in 2008, Schultz closed all the Starbucks cafés in the US for one afternoon, to teach all employees how to make coffee. Its soul was revived and Starbucks got back on track.

$6 million is Starbucks' loss in revenue due to its one-afternoon training shutdown in 2008.

Hopefully you didn't check just one of the boxes in the test below … That's because each of these paths should be taken to make your company fit for the future. But unfortunately, only A and B have a good C-Suite standing. Though most people in general acknowledge that the best lessons in life are learned by failures, only a few business leaders really embrace that learning method.

Jeff Bezos is one of them: In his 2015 letter to Amazon shareholders he wrote: "I believe we are the best place in the world to fail (we have plenty of practice!), and failure and invention are inseparable twins. To invent you have to experiment, and if you know in advance that it's going to work, it's not an experiment." Usually, we think of experiments as something lean and mean. More like a lab exercise than like real business. Bezos doesn't see it this way. "As a company grows, everything needs to scale, including the size of your failed experiments," he wrote in his shareholder letter three years later. "If the size of your failures isn't growing, you're not going to be inventing at a size that can actually move the needle. Amazon will be experimenting at the right scale for a company of our size if we occasionally have multibillion-dollar failures."

Phew! But if you prefer to experiment on a slightly lower budget, look at the other giant that is embracing failure and experiment: Google. Google Earth, Google Maps, Google Mail, they all started as experiments. Gmail even set a record for time in beta mode. After its April 2004 launch, it took more than five years before the beta label was removed. The number of failed experiments at Google is legion. Or, to be precise: 166, according to the "Google Cemetery" website.

Google even developed its own tool to fast-test innovative ideas: pretotyping. It follows on from rapid prototyping, a Silicon Valley methodology where you fail fast but learn fast too. Alberto Savoia, Google's first engineering director and now a lecturer at Stanford University explains it as being "the best way to make sure that the idea you want to build is 'The Right It' before you invest what it takes to build it right." He advocates the 3-digit-case: A few hundred bucks and a few hours of time should be sufficient to bring it to the first test level. Of course you get to a lot of fast failures that way, but, according to Savoia, also get to more successes and fewer missed opportunities.

So why not think about combining C and D. The more experiments you start, and the sooner you cut off the ones that don't succeed, the more you learn – and the better the ecosystem where the successful experiments can thrive.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/TA31_Cover_EN_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act Magazine explores how today’s companies can become robust and survive the coming decade through lessons in innovation, purpose and adaptation.

Stay up to date on the latest global trends and developments in the business world. Subscribe to Roland Berger's Think:Act Magazine now and get access to this and upcoming editions as PDF, including articles by renowned authors and exclusive interviews with thought leaders.