The purpose principle

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/think_act_magazine_purpose_the_purpose_principle_cover_1_download_preview.png)

What does purpose mean to you and your business? Our Think:Act magazine on purpose addresses changing values in the business world.

by Kunal Talgeri

photos by Florian Lang

Read more about the topic

"The purpose principle – missions give businesses strength"

The sandy storybook landscape of the Indian state of Rajasthan has become the backdrop for a forward-thinking new business model. For Nand Kishore Chaudhary and his company, Jaipur Rugs, the reason behind its global success is simple: Stay focused on your purpose and rewards will follow.

A land of heat and dust. It's a lazy cliché sometimes used to paint an unimaginative picture of the sprawling diversity of India. But in Manpura, a village in the northwestern state of Rajasthan, "heat and dust" perfectly describe the scene. Here, in one of the hottest subtropical desert regions on Earth, sand is a permanent fixture – and today the temperature is getting close to oppressive. It's only the beginning of summer and the thermometer is already north of 37 degrees Celsius and rising. Two camels lollop along the sandy track, slowly dragging cartloads of villagers behind them. But this lazy and languid impression is deceptive: There are lots of busy hands at work under the veranda of one of the houses here in Manpura. At Shanti's home, the heat is no excuse to slow down or take a break.

The gritty 36-year-old is hard at work at the loom, doing what she has done for almost 20 years: weaving. Her home is her factory and as she fiddles with a length of yarn, she shouts out instructions across the room to the six other women weavers working for her. That she has reached a position of financial independence and responsibility is no mean feat. Shanti comes from India's weaver community, people often in the lowest income bracket and frequently from the most oppressed societal group dubbed the "untouchables" in the exploitative and antiquated caste system that is still in place in many parts of India. Her rise to the top has as much to do with a forward-thinking business idea as it does to her own hard graft and diligence.

95% and more of Jaipur Rugs' revenue comes from exports, a clear illustration of the company's global mindset.

Shanti learned to weave at the age of 13 and, in keeping with the social norms of the region, was soon married off. She had her first child less than three years later. Life at the loom soon became a struggle made worse by middlemen cheating her out of her wages. Like other weavers in Manpura, she had to borrow money to buy the yarn to make carpets and depended on go-betweens to find customers. She was rarely paid fairly for her work, making less than $ 8 a month – hardly enough to feed a family. When one contractor didn't pay her for two carpets, she was forced to work as a manual laborer, breaking stones and carrying mud to construction sites in the desert heat.

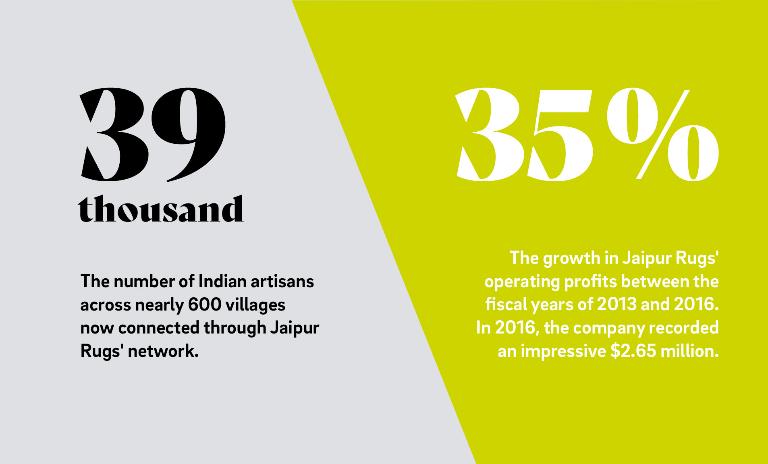

Today, the mother of six's fortune has changed beyond recognition. She is the family breadwinner, earning more than $ 75 a month. She now hosts more than six looms and employs 25 weavers who work at her house from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. weaving award-winning carpets that sell across the world in the US, Europe and Turkey. The agent of change in Shanti's life – and the lives of a staggering 39,000 other Indian artisans – is principled entrepreneur Nand Kishore Chaudhary and Jaipur Rugs, his $23-million company. Ignoring the social norms that paid them little dignity or respect, he made the "untouchables" a key component of his business – as they remain today. "We continue to plan for how to make the weavers' lives easier, ensure that they earn more, develop their capabilities and improve the supply chain," he says. "In the future, they will remain the core of our business. So to be competitive and efficient as a company, we have to focus on continuously developing them."

Chaudhary's vision on how to succeed in a business embedded with purpose was simple: Put the people at the heart of it. "Our job," he says humbly, "is to merely link the weavers to the global customers." Chaudhary enforced global standards on his products and processes right from the start. Had he not, he simply wouldn't have had any buyers. He ensured that Jaipur Rugs adopted healthy labor practices in the supply chain to differentiate it from the carpets business run by contractors and to earn the weavers' trust. And with more than 95% of its revenue coming from exports, Jaipur Rugs demonstrates companies can do social good without sacrificing growth or profitability. "This is about [building] human-to-human relationships," Chaudhary explains. "Focusing solely on business growth is a wrong concept. Growth should happen inside people – the people in your company. How much are they learning? How much is a business developing their leadership and capabilities? That is the only growth a business can sustain."

Embracing his weavers as independent artisans rather than as employees, Chaudhary pioneered a model he calls "doorstep entrepreneurship" when he began his business in 1978: Jaipur Rugs delivers the yarn and other raw material to rural artisans who can't travel for work – some haven't even traveled outside their villages, places scattered across the country with no real livelihood opportunities apart from seasonal agriculture. After receiving careful training, they weave the yarn that arrives on their doorsteps into world-class carpets retailing at top outlets like Home Depot and Crate and Barrel.

A small-town boy himself, Chaudhary had no real exposure to management best practices. So he hit the books and over the years he taught himself key management concepts like Six Sigma and Zero Defects and then he implemented them in the company. "If we had to sustain business for the customers and serve them," he explains, "I realized we have to fulfill those three parameters: zero defect, zero wastage, on-time delivery."

"This is about [building] human-to-human relationships. Focusing solely on business growth is a wrong concept."

His model has captivated business thinkers and commentators not just because of its profitability, but also because of its approach to putting people first and building a world-class business around a disorganized community of artisans. Chaudhary has been invited to address Ivy League institutes such as Harvard and Wharton, but the accolades and attention of business guru C. K. Prahalad speak volumes for the success and structure of the model: Jaipur Rugs was featured in the 5th anniversary edition of his celebrated book "The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits". Prahalad said the company "focused on developing human capability and skills at the grassroots level, providing steady incomes for rural men and women in the most depressed parts of India and connecting them with markets of the rich." It is a source of pride for Chaudhary to be recognized. "It makes me happy that what I have managed to do in an organic way has become a benchmark." And other business academics have also taken notice. "The weavers have developed a sense of financial security and self-reliance," professors Kaushik Roy of the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Calcutta and Amit Karna of IIM Ahmedabad wrote in their 2015 paper "Doing Social Good on a Sustainable Basis: Competitive Advantage of Social Businesses", pointing out that Jaipur Rugs effectively eliminated the middlemen by directly procuring the carpets from weavers who had previously faced exploitation.

Vital to his success, Chaudhary insists, has been treating weavers like family and making them stakeholders – they want the company to succeed as much as he does. Before Jaipur Rugs was incorporated in the 1990s, he spent eight years in Gujarat mobilizing 15,000 tribal artisans to take up weaving. That helped him understand the needs of weavers and their families, which then spurred on another step in the evolution of a new leadership path for his "family": the Jaipur Rugs Foundation (JRF). The JRF builds on the socially progressive work embedded in the business. Shanti's six children are now learning English and math as part of the JRF's education scheme and her husband has enrolled in a skill development program as well. JRF has also ensured artisan certification for more than 5,000 weavers who will get "artisan cards," which is a positive step in bringing legitimacy to a sector like weaving. But as Shanti insists, speaking in her broad Rajasthani Hindi dialect, the most crucial difference the company has made to weavers like her is this: "We get full payment – the money that is rightfully ours. There is transparency. That helps us." For her, the bottom line is that she has a reliable and fair source of income.

The bottom line for Jaipur rugs is similarly rewarding. Having built a capacity of 6,685 looms in 576 villages, its operating profits soared by 35% between the 2013 and 2016 fiscal years. That was an impressive $2.65 million in 2016 – up from less than half a million in 2013. "Our villages have the talent and a range of capabilities," Chaudhary says. "To harness that, India must develop its own models."

Nand Kishore Chaudhary founded the business that would become Jaipur Rugs in 1978. His innovative approach to the carpet industry has earned him multiple accolades including the India Pride Award 2011.

So, as Jaipur Rugs expanded its reach to 576 villages, it did not invest in office space for weavers and looms. Instead, it variabilized capital expenditure by empowering branch managers to find weavers who could host looms in their houses. The house owners are compensated for hosting looms. "While this appears to be a logistical challenge and complex at first, how else will we tap into the artisans' creativity?" he says.

Besides progressive work done in recognizing artisan skill and lifting people like Shanti out of poverty, Chaudhary's maverick attitude to business growth also plays a part in helping to sustain a positive new business model that has purpose and social improvement at its core. He is almost evangelical about the purpose of business: "I feel the social issues [in India] can be resolved only through business. There is no other way for organizations or government to redress these issues. The capabilities required to solve these issues are available to a businessman. If we create jobs, then the issues of clothing and housing also get solved."

But that doesn't mean business at all costs or unbridled growth. Chaudhary says that as the business grows, there is a danger of distancing the core weaver base. "That's where the business starts dying." He maintains that keeping an eye on what matters and bringing about positive change are also aspects of the purpose of business. "Purpose is the only thing that is important because without that a business will ultimately lose its way. Purpose," he emphasizes, "is everything." And as the business becomes bigger "it becomes about keeping its soul alive," he adds with a kind of steady certainty. For Jaipur Rugs, that soul is the weaver community, and it's a soul that sings. As the weavers' fingers knot the threads at the loom, they raise their voices in song. And in the heat and dust, Shanti keeps an eagle eye on quality, overseeing the weaving of a carpet that could change all their fortunes.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/think_act_magazine_purpose_the_purpose_principle_cover_1_download_preview.png)

What does purpose mean to you and your business? Our Think:Act magazine on purpose addresses changing values in the business world.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.