In the United States, the anticipation of consistently having clean and safe tap water is regrettably not always met. A myriad of factors converges, exposing millions to contaminants in drinking water, some of which pose substantial health risks.

Opportunities & challenges in new regulations of ‘forever chemicals’

Understanding new PFAS regulations in the U.S. and EU

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) - , contaminants more commonly known as ‘forever chemicals’ - have become a significant concern worldwide due to their persistent, bioaccumulative nature and adverse health effects. This class of more than 14,000 chemical compounds has been widely used for decades in various industrial and consumer products for their unique properties, including resistance to heat, water, and oil. However, growing evidence shows that PFAS pose risks to human health and the environment. Exposure has been linked to deadly cancers, liver and heart impacts, as well as immune and developmental damage to infants and children.

As a result, strict new regulations have begun to take effect worldwide. Governments and environmental authorities are setting or expanding new limits for PFAS in drinking water as well as testing and monitoring requirements. They are also considering potential restrictions on wastewater discharge and the land application of biosolids.

"…the approaches...for managing...[PFAS] differ between the U.S. and Europe. These differences will influence the strategies taken...and have a range of implications for investment, growth opportunities and ongoing management."

With new regulations come increased compliance and treatment costs for utilities and industrials. Growing public awareness regarding these ‘forever chemicals’ and their health impacts is further increasing the pressure across the water ecosystem to act. Conversely, regulatory changes are creating opportunities for investors to increase their exposure to water investments and for water technology providers to gain new market share.

While PFAS contamination is a global issue, the approaches and regulations for managing and addressing these contaminants differ between the United States and Europe. These differences will influence the strategies taken by water and wastewater utilities, technology providers, investors and industrial companies and have a range of implications for investment, growth opportunities and ongoing management.

Recent changes in the regulation of PFAS

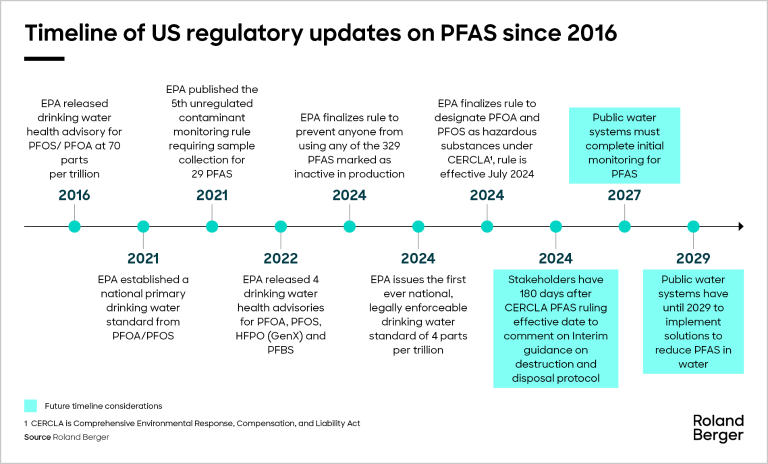

2024 has already seen several major updates in the regulation of PFAS in the US. Most notably, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced legally enforceable Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for six PFAS in drinking water in April. Two common contaminants, PFOA and PFOS, are limited to 4 parts per trillion (ppt), while PFHxS, PFNA, and HFPO-DA are limited to 10 ppt. Additionally, the EPA set a Hazard Index MCL for PFAS mixtures containing at least two or more of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, and PFBS to account for the fact that low levels of individual PFAS would not likely result in adverse health effects but may pose health concerns when combined.

These new standards are considerably more stringent than the initial advisory of 70 ppt set back in 2016 and exceed any limit that states had individually set. The EPA also established health-based, non-enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) of zero for PFAS with PFOA, reflecting the latest science that shows no level of exposure is without health risks.

Under this rule, public water systems must:

- Monitor for these PFAS and complete initial monitoring for the new MCLs by 2027

- Begin providing the public with information on the results from 2027

- Implement solutions to reduce PFAS (if they exceed MCLs) by 2029

- Take action to reduce PFAS and notify the public of any violations of MCLs from 2029

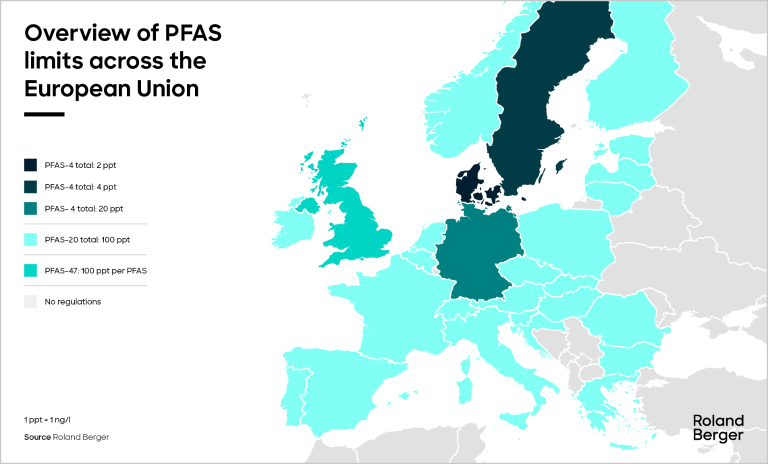

Action on PFAS is also ramping up across Europe, with updated EU-wide limits coming into effect from 2026. The recast Drinking Water Directive (DWD), the EU’s primary drinking water law, limits levels of 20 individual PFAS to 0.1 µg/L, roughly equivalent to 100ppt. Further, total PFAS in drinking water is limited to 0.5 µg/l (~500ppt). From 2026, drinking water will need to be assessed and pollutions tracked, with actions taken to remove PFAS in the event of noncompliance.

Several countries have chosen to enact stricter measures for the sum of PFAS-4 (PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS) that are closer to those in the U.S. These include Denmark (2ppt), Sweden (4ppt), and Germany (20ppt by 2028). The UK has a 100ppt limit but extends the restriction to 47 different types of PFAS, as opposed to the 20 across the EU.

To implement a more sweeping ban against PFAS substances as a category, five EU member states, including the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Norway and Denmark, have submitted a proposal to ban the manufacture and importation of 10,000 PFAS substances. This is the first time that a restriction dossier has covered such a vast class of substances, with the goal of avoiding a cascade of substitutions for substances in the same class.

Register now to access the full study and explore the latest regulatory developments in both the US and Europe regarding PFAS, and the emerging challenges and opportunities. Furthermore, you get regular news and updates directly in your inbox.