Portfolio Transformation in the Chemicals Industry: Six Success Characteristics

Clear strategic intent, strong corporate center are key to successful corporate portfolio transformation

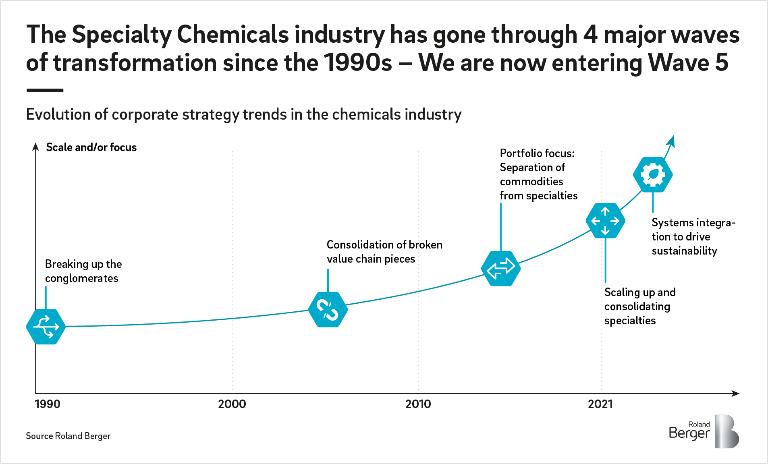

Since the early 1990s, the chemicals industry has undergone four waves of M&A-driven transformation. The first wave saw conglomerates break up. The second wave saw broken value chain pieces consolidated. The third wave saw a portfolio focus as companies separated commodities and specialties. The fourth wave saw specialties consolidate and scale up.

We have now entered a new wave of chemicals industry transformation that is driving current M&A historic highs. Enabled by abundant capital, this new wave corresponds to the transformation of portfolios driven by chemical companies’ quest for sustainability and customer-centricity.

Looking at past chemical companies’ most successful transformation efforts, i.e. the ones which drove the highest levels of shareholder value creation, there is a clear association with improving strategic coherence. Companies that transformed successfully were able to shift their portfolios to a clear set of related businesses and align internal capabilities to their external vision and mission positioning, thus demonstrating that they were the high-value owners of their portfolio businesses.

For more information on our views on strategic coherence, please refer to Roland Berger's article on How Chemicals Companies Create Shareholder Value.

As we have seen from prior waves, transformation is challenging. For every example of success, examples of failures abound. Financial markets take time to be convinced that a successful transformation is underway. Only when there is significant evidence of transformational moves (e.g., stated strategic intent and actions, such as a transformational deal aligned with the intent) do markets credit the company for its future position.

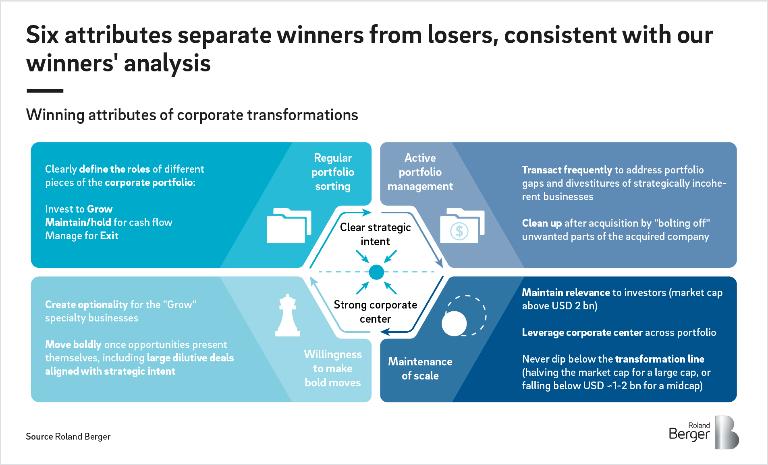

What does managing strategic coherence through transformation mean for chemicals companies? Specific lessons can be extracted from previous chemicals industry transformation waves. Six success characteristics stand out, which are explored in detail below.

First, companies need a clearly articulated strategic intent. Second, companies should regularly sort their portfolios to identify core businesses. Third, companies should actively manage their portfolios. Fourth, companies should maintain financial scale to maintain investor relevance. Fifth, companies must be willing to make bold moves. Finally, companies must have a strong corporate center that drives leadership alignment around strategic intent.

Clear articulation of strategic intent

To ensure internal capabilities (what the company does best) are aligned, with external positioning (serving markets that value the capability), companies should have a clearly articulated vision that should be communicated to both internal and external stakeholders to the point that it is embedded and understood as part of the company’s culture. Since long-term strategy often conflicts with short-term priorities (both internally and externally), companies must be disciplined in executing their strategic intent over the long run instead of shifting gears when the going gets tough for a quarter or two. Impatience can doom even the most promising strategies.

For example, a few years ago, a mid-size diversified chemicals company radically changed its investor perception from average growth to high growth – and, with it, its trading multiple - by stating a simplified, compelling vision to enable electrification of transportation clearly associated with its acquisition of a leadership position in lithium. In the subsequent years, it demonstrated its commitment to this vision through aligning its portfolio and capability with this vision. It did not abandon its vision even in the face of stock price volatility correlated with underlying lithium price volatility. The company is now reaping the benefits of that commitment.

Regular portfolio sorting

Companies should regularly sort their portfolios by assessing which businesses are aligned with the strategic intent and can win based on a company's internal capabilities. Along these lines, they should divest businesses that have higher value in other portfolios. Companies that want to succeed should not have any sacred cow businesses.

Another diversified chemicals company identified early that two of its businesses – agricultural chemicals and food ingredients – would be its growth platforms, and the other three businesses would be divested. It then focused its capital spending on these two platforms and used the other businesses as cash generators and, eventually, as acquisition currency.

Active portfolio management

Companies can actively manage their portfolios by balancing acquisitions with divestitures. Many chemical companies tend to focus on acquisitions and do not dispose of non-core businesses in a timely fashion. Passive portfolio management can lead to or be perceived as empire-building, an undesirable position in which a company looks to expand at all costs rather than do what is best for shareholders. It can also reflect our tendency to double down on past behaviors or decisions even if the outcome is unappealing - which is in turn enabled by groupthink at companies where conformity is rewarded and people who cast healthy doubt on strategic execution are penalized.

One large diversified chemicals company did a series of large acquisitions to execute its vision but chose not to divest acquired portfolio pieces that did not fit, tucking them into existing businesses instead. This resulted in increased internal competition for capital, sustained high balance sheet leverage, and investor confusion, causing poor stock price performance over the years.

Active portfolio management can catalyze funding investment in more strategically aligned assets and pre-empt activist pressures. But it should be done responsibly. Excessive portfolio sorting can create a perception of indecisive or cloudy strategic execution. Companies should not divest for the sake of managing the portfolio; they should only get rid of businesses that do not fit.

Maintenance of financial scale

Retaining a critical mass to enable public equity market relevance and scale in corporate functions requires companies to maintain financial scale. Exiting non-core businesses all at once may not be possible for mid-size companies as it may make them too small to maintain inclusion in desirable trading indices or even justify a public equity listing, and it may also leave them with a significant corporate cost burden relative to the size of the portfolio. And whether a company suffers formal costs (like exclusion from trading indices) for divesting too quickly or too much, investors often consider size a virtue in and of itself. As the adage goes, perception is reality.

One small-cap specialty chemicals company defined its strategic intent around chemicals and materials leadership. After sorting its portfolio, it made the decision to quickly divest a non-materials business. However, it lacked an immediate plan to use the funds to invest in other more strategic businesses. Thus, the firm lost the necessary scale to succeed as a public company, and, despite having a debt-free balance sheet, it saw market capitalization drop significantly in subsequent weeks.

Willingness to make bold moves

Why should companies be willing to make bold moves? You never know when an opportunity will strike, and boldness can enable unique leadership opportunities. Companies should not be afraid to execute large, dilutive deals if they align with the long-term vision. Many firms miss the forest from the trees by strictly adhering to “the way it’s always been done” instead of thinking long-term about industry trends and strategic intent. Alternatively, impatience and fear can preclude companies from considering acquisitions that may hurt the stock price in the short run but help it in the long run. Financial markets reward these big, bold moves if they bring to life a previously announced strategic intent.

The Ag chemicals and food ingredients company described above got an opportunity to acquire a missing piece in its Ag portfolio. Even though its origins were in food, it made the bold move of swapping its food business for the desired Ag business, thus creating a unique Ag leadership position – a move that financial investors cheered.

Strong corporate center

Finally, a strong corporate center can help a company define its strategic intent, drive leadership alignment around clear business roles, and align the corporate structure while shaping the culture around the future vision. The strength of the corporate center is paramount.

One successful company had clearly identified that one of its businesses would get all the company's cash flow provided by the other two businesses in its portfolio. In talking to business unit executives at this company, the level of acceptance of business leaders with the role of their businesses in the portfolio was striking. There was no intent to compete for capital or vie for a higher-level leadership position. Executives understood that they were all on the same team; what’s good for the company is what’s good for everyone at the company. Organizational structures vary across companies and industries, but the necessity of companywide alignment around a stated strategy is universally important.

At another less successful company with over ten business units, nearly every unit leader competed for capital and C-level attention, in pursuit of the next CEO role. This drove a "fiefdom" culture and inefficient decision-making across and within businesses. Had a strong corporate center been in place, leaders would’ve prioritized the success of the company over their personal success or the success of their respective businesses.

Many chemicals companies do one or some of these things right in their transformation efforts. But these success characteristics do not work in isolation. For instance, an appetite for bold moves won’t mean much in the absence of a strong corporate center that can get the whole company behind those bold moves. A clearly articulated strategic intent will fail in the absence of a companywide willingness to take short-term lumps in favor of long-term gain. Regular portfolio sorting can backfire if companies fail to maintain financial scale.

Like an athlete looking to improve their skills, a company must think about how each piece of the puzzle fits with the big picture rather than seeing each of these six success characteristics as standalone attributes of successful transformations.

As chemical companies embrace the coming wave of transformation by considering acquisitions and divestitures that drive higher customer-centricity and align with sustainability goals, they will have many options. The key to superior shareholder value creation will be the fine art of selecting the right options and executing in a purposeful and timely fashion to manage strategic coherence. As with other industries and disciplines, success in chemicals transformations is where preparation and opportunity meet.

_person_320.png?v=770441)