How crisis can fast-track business transformation

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/TA_32_001_EN_Cover_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act Magazine explores how successful companies face the challenges of our time with creativity and agility to enter a New World.

Article by Steffan Heuer

Photos by Tony Luong

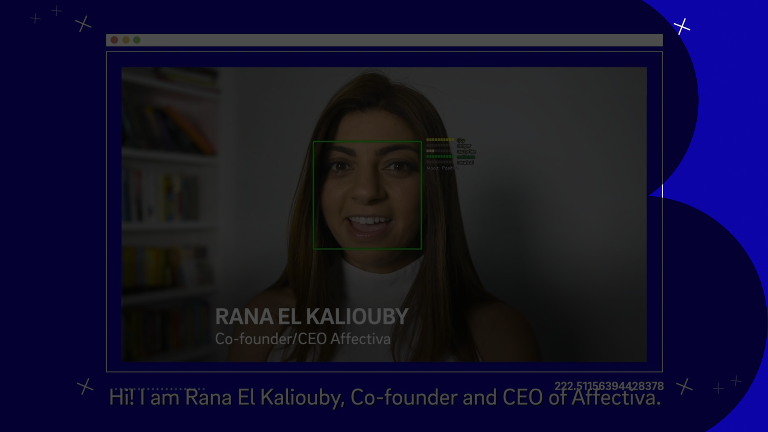

AI systems need to understand human emotions to make technology more humane and useful, says researcher-turned-entrepreneur Rana el Kaliouby.

Scenes likes these play out in millions of cars every day. The driver is glancing at her phone, trying to quickly send a text while stopped at a light. Or is tired after a long day. Or engaged in a lively conversation or argument. Sometimes, these very human behaviors lead to a moment – or several seconds – of distraction and result in a fender bender. Even sophisticated driver assistance tools cannot prevent all crashes. And that's no accident, says computer scientist Rana el Kaliouby, who herself once totaled a car when she was distracted.

Modern software systems can keep us in a lane or apply the brakes, they still don't understand humans and our emotional baggage. "Automation and AI in the automotive industry has historically been very focused on what's happening outside of the car, but the cabin is still kind of a black box. How many people are in the vehicle? How are they interacting? What objects are they holding? Are they agitated, tired, distracted? All these contextual cues are very important," explains the researcher who more than a decade ago turned her scientific passion into a company called Affectiva that's offering what it calls "Emotion AI."

"Traditional computers are emotion-blind. They have trained us to behave as if we lived in a world that was completely devoid of emotions."

Computers excel at crunching numbers, say identifying a red light or executing a command, but they were not built for rich human interaction. Humans use these systems, whether it's a device or a social media platform, oblivious to the fact that their digital counterparts can't recognize or respond to their moods or feelings. Her verdict: "Traditional computers are emotion-blind. They have trained us to behave as if we lived in a world that was completely devoid of emotions."

The former MIT researcher thinks we can and ought to do better. She wants to build holistically intelligent systems with emotional intelligence (or EQ) that adapt to how we feel. "Emotion AI" could be a much-needed antidote to the dehumanizing effect of technology, el Kaliouby believes, as we are becoming more dependent on algorithms, apps and platforms to be productive and stay connected – from semi-autonomous vehicles and social robots to sensor-laden wearables and virtual spaces for conducting job interviews or learning. "We need our technology now more than ever, but we need to make it smarter, better and more humane."

This call to merge a computer's considerable IQ with commensurate EQ is not just a professional goal but also a deeply personal one. Thumb through el Kaliouby's book Girl Decoded, published in spring 2020, and it’s clear that her journey from a strict Muslim home to successful computer scientist at the MIT Media Lab and finally CEO of a pioneering tech startup is also about decoding her emotions as the rare female programmer wearing a hijab. "I spent my years coding, but at the same time, it was also a process of figuring out who I am and what I stand for," she summarizes her life in a male-dominated tech world.

As el Kaliouby tells it, she was always a "nice girl." Born in 1978, she grew up in a conservative household in Cairo and later Kuwait. She excelled at school, eventually winning a scholarship at Cambridge University, where she found her calling. "I decided to study computer science and became fascinated not by the nuts and bolts of technology, but how technology changes and empowers the way we communicate as humans."

2.2% — The percentage of all venture capital raised in the US in 2018 that went to companies founded by women.

She can even pinpoint the moment she realized how regular computers are degrading or even damaging human interaction. It was a winter afternoon at Cambridge, long before webcams and smartphones became ubiquitous, and el Kaliouby was talking to her then-husband back in Egypt by way of typing.

That's when it hit her, she recalls, that in spite of all the hours she spent with her computer, it had "zero clue" how bad she felt at that moment. "We all communicate mostly digitally, but 90% of human communication is nonverbal – via our face, our voice, our body language and gestures. All that is lost online. It dawned on me that we have to redesign technology in a way that incorporates nonverbal communication."

From this realization sprang the motivation to write her master's thesis on building a face detector and a facial landmark detector, which led to a PhD in computer vision and machine learning. Once she arrived at the MIT Media Lab, el Kaliouby kept pursuing her research in emotion recognition, initially focused on how to help people with autism.

She found a like-minded spirit and mentor in MIT Professor Rosalind Picard who had coined the term "affective computing" back in 1997 when she published a book by the same title. The collaboration led to spinning a startup called Affectiva out of the university in 2009. The two initially steered clear of using the word "emotion" because they worried it wouldn't go over well in the predominantly male tech world. (Picard left the company in 2013 and founded another startup called Empatica.)

$50 million — The total venture capital raised by Affectiva between its founding in 2009 and April 2019.

The company's first commercial foray was a product to help advertising and media firms decode video clips of audiences to measure the emotional impact of their content, be it an ad, a TV show or a movie trailer. It was different from the original vision in the medical sphere, but reading people's minds for market research turned out to be a commercial success. According to the company, Affdex is currently used by a quarter of the Fortune Global 500 companies in 90 countries, among them Mars, Kellogg's and CBS.

Fast forward to 2015 when el Kaliouby was invited to give a TED Talk before a select audience of technology luminaries in California. Her talk entitled This app knows how you feel – from the look on your face put the entrepreneur on the map. The surge in interest also convinced the company to come up with the term "Emotion AI." It was a catchy way to stake a claim in an emerging field where a growing number of incumbents and startups were offering AI tools to read faces and minds, do sentiment analysis or engage with empathetic chatbots.

Competitor Emotient, spun out of UC San Diego, was snapped up by Apple in 2016. Then the car companies came calling. "They were saying, we love what you do with emotions and cognitive states. Can you make it work in a car?" Following the inquiries, the startup expanded its capabilities to include voice analysis by using a training set of customer service calls in English, German and Chinese. The software, though, is not listening to the actual words, but only how fast and how loud somebody is speaking, whether people are speaking in a monotone or showing a variation in pitch and intonation, which indicates excitement.

The end result is a package called "In-Cabin Sensing" that trains cameras and microphones on the driver and passengers. El Kaliouby is quick to point out that people need to know they are being observed and explicitly opt in, even though the data never leaves the local device. The company says it's working with a roster of big manufacturers, among them Aptiv, BMW and Porsche as well as leaders in the field of autonomous driving such as chipmaker Nvidia.

"Let's humanize technology before it dehumanizes us."

Understanding the complex web of emotions, facial expressions and voice utterances is a work in progress. Affectiva, which now employs 90 people at its headquarters in Boston and Cairo, has accumulated what it calls the world's largest "emotion data repository" based on more than 9.8 million faces and four billion frames of video collected in 90 countries.

She stresses that technology like hers must be designed with the goal of diversity and inclusion from the start. "A European car company sent us a training set of faces, but they were all blue-eyed, blond middle-aged guys," she recalls of the data set. "We told them this was not good enough. If our technology doesn't work with darker-skinned people like me, or with people who represent diversity in all of its forms, then that’s an epic fail from a business and ethical standpoint."

Giving cars an EQ to complement their IQ is but one area where el Kaliouby sees promise, especially as human-to-human interaction is somewhat tainted by the coronavirus pandemic. "We will see a lot of innovation using technology like ours that can quantify and give you analytics on top of a videoconferencing or livestreaming platform."

It would help not only presenters to get something akin to emotional ratings in real time, she believes, but also aid audiences and hosts. "If the viewers opt into giving an algorithm access to their device’s camera and the algorithm aggregates reactions, the audience can feel they're contributing something that's shared with everybody who's watching."

El Kaliouby wants to see Emotion AI roll out in other areas to "help us become happier, healthier and more empathetic individuals." She envisions social robots in health care settings that can perform the intake assessment at a hospital instead of a nurse and only send those to see a human doctor who need attention. "There is evidence that facial and vocal biomarkers exist for things like depression, stress, anxiety or Parkinson's disease.

While we're stuck with our devices for hours and hours every day, these could be opportunities to get a pulse on a person's mental and emotional state." Using better AI tools can also improve the hiring process. While HR departments are already striving to become aware of and correct for human biases, algorithms have the potential to conduct job interviews without being distracted by the gender, ethnicity, age or looks.

Instead, they can home in on the nonverbal communication to determine if somebody is a good fit. And finally, AI with a helping of emotional astuteness stands to improve online learning systems because educators would be able to detect the level of engagement of each student and tailor their approach accordingly

Rana el Kaliouby is the co-founder and CEO of Affectiva. The Boston-based company was spun out of the MIT Media Lab in 2009. She has been recognized by Forbes as one of "America’s Top 50 Women In Tech," and by Fortune Magazine in its 2018 "40 under 40."

As good as this sounds, making AI systems even smarter and responsive to human emotions has serious downsides. Historian Yuval Noah Harari has tackled the inherent problems of human-machine interfaces in three books so far. His main criticism, as he explained in a discussion with Wired, is this: "To hack a human being is to understand what's happening inside you on the level of the body, of the brain, of the mind, so that you can predict what people will do ... The algorithms that are trying to hack us, they will never be perfect … You don't need perfect, you just need to be better than the average human being." It's a valid concern addressed in the European Union's "Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI" presented in April 2019.

El Kaliouby admits concerns around privacy, manipulation and discrimination arising from the deployment of emotionally intelligent machines at scale. "We don't apply our technology in areas like security, surveillance or lie detection, even though we [might] make a lot of money... but for use cases like these where there is no opportunity for people to opt in and consent to its use, and there's potential for bias and harm."

Instead, the fairly small company is part of the "Partnership on AI to Benefit People and Society" (PAI) which comprises 100 members from industry, academia and NGOs in 13 countries, among them Amnesty International and American Civil Liberties Union. "Technology is moving really fast, and we need it right now.

But that's no excuse to be sloppy," says el Kaliouby, who would like to see a label on tech products and services that tells consumers whether the underlying AI was ethically derived, similar to organic labels on food. "As we train young people to become the future AI leaders of the world, it's important that privacy and the unintended consequences of technology are part of the curriculum. Let's humanize technology before it dehumanizes us."

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/TA_32_001_EN_Cover_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act Magazine explores how successful companies face the challenges of our time with creativity and agility to enter a New World.