Breaking the rules

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/Think_Act_Magazine_Breaking_the_rules_Cover_download_preview.jpg)

Is breaking the rules a crucial skill? We examine how the people who have made their own rules also significantly shaped the world of business.

by Detlef Gürtler

illustrations by Joni Majer / wildfoxrunning

Read more about the topic "Breaking the rules"

About 2,350 years ago, a little town in the middle of Asia Minor held the key for ruling the whole continent. Or rather, the knot. An old prophecy said that whoever could disentangle the puzzling knot displayed in the temple of Zeus in Gordion would become king of Asia. Countless efforts had proven again and again, year after year, that it was an impossible knot to untie – until a young man named Alexander, then leader of the Macedonian army, came up with a solution. He simply took his sword and cut the knot in two. He – zap! – broke the rules and the knot to rule the region. A kingdom for a rulebreaker.

Cutting the Gordian knot. It's probably every leader's dream. And it's also every leader's nightmare. It's a dream, because the ancient legend shows how to eliminate complexity and the bureaucracy that surrounds it. And it's a nightmare, because you might just as soon end up not simply a rulebreaker, but broken as well. Someone younger or bolder, more audacious or more reckless, a latter-day Alexander the Great or Donald the Trump could come along and destroy in a moment what took generations to build. Yes, it's tempting to "unfollow" the rules – but is it really worth the cost?

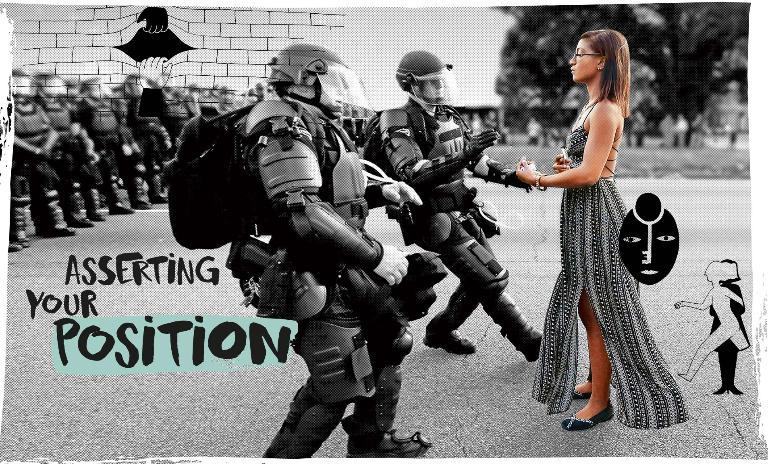

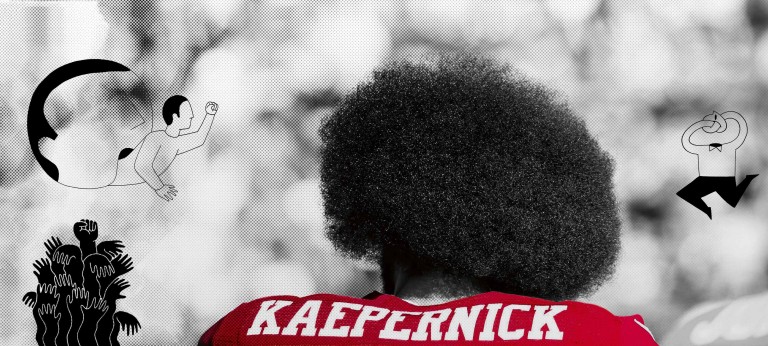

It seems like a common pattern: The person who breaks the rules gets praised to the skies. That moment when someone does something no one's ever done before and enters the history books – like taking your seat on a bus (Rosa Parks), picking up grains of salt (Mahatma Gandhi) or crossing a border river (Julius Caesar). Even if "there's nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come," to paraphrase French writer Gustave Aimard, it still requires a definitive action to bring the effects of that idea into the real world. And that action is, more often than not, an action that breaks the rules.

Rulebreaking heroism should nevertheless be taken with a pinch of salt. There's an obvious "survivor bias": Less successful rulebreakers don't find their place in the history books. Take Fritz Wandel. He called for a national strike in Germany the day after Hitler came to power but only the workers in his hometown of Mössingen followed his call. Wandel survived the Third Reich in prison, and after 1945 worked in Mössingen's cemetery.

The moment you break a rule, you simply don't know if it will break the system or break your life. One of the most iconic of these moments in business came in 2007 when an absolute newcomer to the mobile phone industry (Steve Jobs) decided to equip his first phone (the iPhone) with none of the physical interface elements used up until that point, putting his money on the touch screen instead. The obvious question was: "Will users be willing to give up everything they know for something they've never used before?" Internet pioneer Marc Andreessen asked Jobs that very question just before the iPhone was launched. Jobs' answer? "They'll learn." And we did.

One of the most outspoken protagonists of rulebreaking business is Seattle-based aerospace engineer and tech philosopher Venkatesh Rao. The world is "breaking smart" from its own past, Rao says – and to emphasize this, he published his essay series Breaking Smart not as a book, but as "Season 1," a 20-episode blog designed for binge reading. For the new to succeed, the old rules need to be broken. As soon as they "start to collapse under the weight of their own internal contradictions, long-repressed energies are unleashed," he says. If we want the gains from the new to be bigger than the losses from the old, the world "depends on free people, ideas and capabilities combining in unexpected ways."

Yes, it happens, and often. Rupert Murdoch's 1986 anti-union crusade in the UK ended trade unions' grip on the British economy and set a hypercapitalist wave in motion. Only by scrapping the postwar rules for the German economy in 1948 could Ludwig Erhard ignite the "economic miracle," while the collapse of the Shogunate era in Japan in 1867 paved the way for the Meiji Restoration and the creation of a modern and powerful country.

But, no, not every collapse of the old ways will lead to a thriving new world. The Dark Ages that followed the implosion of the Roman Empire is one historical example. And the demolition of the rule-based world order we are currently witnessing may become equally historical. The Trumpian transformation may lead to a deal-based world order or the collapse of the last remaining superpower, unleashing a lot of long-repressed energies. Whether that will lead us into a new era of enlightenment or into a new Dark Ages remains to be seen.

Why not just keep the rules we have if there's so much risk in breaking them? According to Leonard Mlodinow, that's because we're human. "The human species likes change and is attracted to change." Mlodinow, a theoretical physicist and science author, calls this human capacity "neophilia, the love of the new." He sees this "elastic thinking" as a unique feature of our species: "Squirrels don't get bored if they do the same thing all the time. They just keep doing it. But humans do."

And according to history, it's also because times are changing. Almost nothing seemed to change in the communist parts of Europe after Josef Stalin's death in 1953: brutal, but steady dictatorships; lousy, but self-sustaining economies; a quasi-frozen superpower status. Until Mikhail Gorbachev started thawing the icy fortress and the whole Soviet empire melted. Could someone else, a leader like Vladimir Putin, have saved the empire by sticking to the rules instead of breaking them? Unlikely: The pillars of its imperial power were brittle, or rotten, from within. And there is almost nothing in the world of politics or business as difficult as changing the (dysfunctional) rules of a (formerly) highly successful organization.

This is where the manager's nightmare kicks in. If the need for change collides with a company's rules, change wins – and the company loses. The problem here is not the change in itself: The R&D departments and the creativity of the workforce are great sources for innovation and industry-changing revolutions. Xerox invented the PC and the mouse, photo giant Kodak was the first company in the world to build and market digital cameras and Sony was one of the first movers in the field of digital music players. But these inventions didn't fit into the architecture of the companies, so their potential could not be fully unleashed and someone grabbed the prize. In fact, in all three of these cases, it was Apple.

The new kid on the block doesn't have to follow any of the rules established organizations have written for themselves, argues Rebecca Henderson. The professor at Harvard Business School identifies rule keeping as a competitive disadvantage for incumbents: "They may invest heavily in the new innovation, interpreting it as an incremental extension of the existing technology or underestimating its impact on their embedded architectural knowledge. But new entrants to the industry may exploit its potential much more effectively, since they are not handicapped by a legacy of embedded and partially irrelevant architectural knowledge."

"Disruption occurs when successful firms fail because they continue to make the choices that drove their success," says economist Joshua Gans, professor for strategic management at University of Toronto and author of "The Disruption Dilemma". So keeping the rules is effective – until it isn't. And you can only know in hindsight when the right time to break them was, or might have been. One of the most successful players in contemporary business, Warren Buffett, stuck to one of the most simple rules ever: "Purchase, at a rational price, a part interest in an easily-understandable business whose earnings are virtually certain to be materially higher five, 10 and 20 years from now." Buffett publicly doubted his approach during the dotcom frenzy in 1999/2000 as others reached higher returns – but he didn't break his rule. This was the right decision, of course; but who could have known that at the turn of the millennium?

Breaking the rules is, of course, best done when you're like Alexander – young, bold, have nothing to lose and everything to gain. Take Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. Other entrepreneurs acted less brilliantly. For example, Travis Kalanick left Uber because of controversies about his unethical behavior and Elon Musk's Tesla might be on track to hit a financial wall: Annoying traditional capital market participants while still burning billions of cash each year seems not to be the best survival strategy.

Even the most charismatic conquerors won't be successful in the long run without keeping some of the old rules – or building new ones. Alexander the Great secured his impact by "remixing," literally marrying Greek and Persian culture in 324 BC. The offspring, Hellenism, ruled the Occident for half a millennium and is still one of the strongest legacies of Western culture. Google's "don't be evil" mantra served as a useful guideline for a company sailing towards uncharted territories, just like Ken Olsen's "do what's right" was partly responsible for the rapid growth of the computer builder Digital Equipment Corporation during the 1970s – because it attracted the best computer engineers in the world. Just like sticking to the same rule a decade later accelerated its decline because the same engineers had a deeply rooted aversion to the toylike PCs that attacked their beloved mainframe machines and transformed the whole industry.

So those who make the rules should break them. And the others, the ones who break the rules, should make new ones. It seems like they all could meet somewhere in between, doesn't it? Leonard Mlodinow makes one recommendation: build new rules bottom-up while in the process of change. In the traditional top-down method, people are obedient and follow authority. But if work is organized bottom-up, "all the individuals somehow work together in a way where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts." There's no need to burn the company's rulebook, "but you really have to be able to face the change and go with it, not resist it."

Venkatesh Rao favors a slightly different solution. In his view, the guideline created by the Internet Engineering Task Force for software engineering can serve as a business rule, too: "rough consensus and running code." You don't have to agree on everything, as long as you head more or less in the same direction, the results will be just good enough. Business in the Age of Software will generally lead to "pragmatic approaches prevailing over purist ones." Rules simply become too flexible to be broken. But that won't work for every business. The best-known counterexample is, of course, rocket science. Landing a man on the moon doesn't work with rough consensus – only with strict protocols. The 1986 Challenger disaster proved with disastrous consequences what happens if you overlook the rules to get things done.

The more a company relies on complexity and perfection, the tougher it is to thrive in an approximation-only atmosphere. One solution is to find an equilibrium between breaking, keeping and building rules not by gathering everyone in the middle, but by manning the extremes. This is a rather common strategy in family businesses when preparing for generational change. The younger generation often gets a first leadership position in a "new" business segment – working with new technologies and/or developing new products. This way they are able to find their own business and work style. Outside of the parental shadow, the offspring gains experience of how to rewrite the company’s rulebook – and how not to.

In non-family businesses, similar strategies are less widespread, but can nevertheless be the best solution to renew a company, or parts of it. Take Nestlé's Nespresso: In the early 1980s, the coffee capsule brand was marketed within Nestlé's established coffee division. It failed miserably. The B2C Nescafé managers couldn't grasp the B2B system of selling machines and capsules as a bundle. Office clients didn't like the price; hospitality clients didn't like the look and feel and then problems in production and logistics came on top. Then, in 1986, Nestlé established Nespresso as a separate, wholly Nestlé-owned company, its top management was recruited externally and the brand philosophy was focused on selling convenience, not just coffee. This was of course still incompatible with the traditional Nescafé world – but it succeeded.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/Think_Act_Magazine_Breaking_the_rules_Cover_download_preview.jpg)

Is breaking the rules a crucial skill? We examine how the people who have made their own rules also significantly shaped the world of business.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.