Exploring complexity

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/roland_berger_think_act_magazine_navigating_complexity_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

Don't miss our article with Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler, as well as much more food for thought.

by Detlef Gürtler

illustrations by Martin Nicolausson

The brain is the best mechanism we have for managing complexity. Yet, we are just beginning to understand how complex its own processes really are. Can we take lessons from how the brain manages the body to find new ways to manage business better? And what, exactly, would such a "neuroscientific management system" look like?

You are in front of a computer or hold a mobile device in your hands. You are reading this article and these words right now and making sense of them. But before you settled on this story, you probably flipped through a series of article pages, your eyes darting across the displayed words and quickly scanning the headlines and images. When an article caught your attention – like this one did – you stopped. You decided to take a deeper look. You let the text and images register a little more deeply. You engaged. Now, take a step back. How exactly did you go through this whole process? Did you consciously instruct your fingers to click the pages? Did you tell each hand and each finger individually what to do? Did you register each and every word, every picture and illustration?

"The brain uses top-down guesses that are based on rudimentary input information."

When you break down what seems like a simple routine task – like reading an online-magazine – you quickly realize that it is an extremely complex undertaking. Your brain is constantly both receiving and sending signals: It is doing a lot of work without you even knowing it. If you were consciously aware of every signal, or had to absorb and process every single movement or detail that your brain picked up – every word, image, color or page texture – you might not get anything done at all.

The good news is that you and your brain don’t have to work that hard – but you and your brain do have to work together. And it is worth considering how the harmony of complex cognitive processes and decisions work together and then, perhaps, applying them to how you run your business.

No company has ever been managed in the same way our brains manage us. For a moment, let us consider the extraordinary talent our brains have for reducing complexity. Here’s an example: About 11 million bits of information reach the brain every second. But only 40-50 of these 11 million merit conscious processing. So what we call "thinking" is an activity that takes place only after we have reduced the data volume by a factor of somewhere around 1:250,000.

"The brain does not only receive data from the sensors and organs, it also delivers continuous forecasts to them."

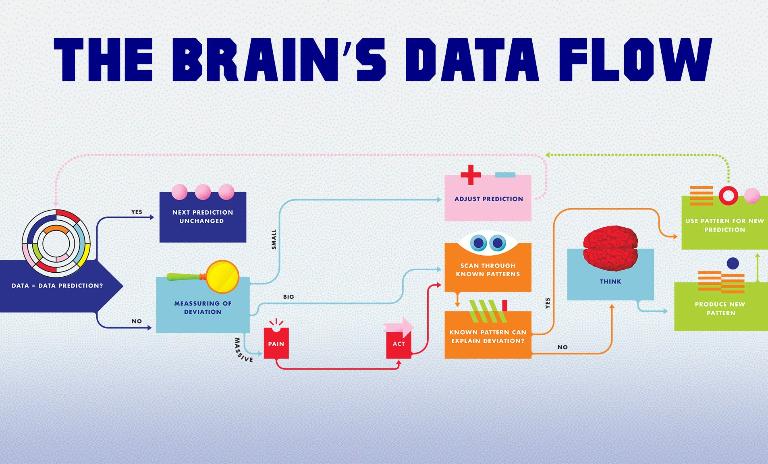

Some of the remaining bits per second are processed unconsciously; thank your instincts for that. It’s a simple process: if (stimulus), then (response). But let’s think about this for a second – and yes, alongside all of the other data that is still flooding in. A huge proportion of all the incoming data doesn’t even reach a level requiring analysis. The brain knows what it does and what it doesn’t have to worry about. In short, it uses a technique akin to predicting the future. It works on the basis of expectation and acts accordingly, only making an intervention if something is not right.

Lars Muckli, a neuropsychologist at the University of Glasgow, has put his finger on exactly that point. He has even gone so far as to call the brain a "prediction machine." The brain, he explains, does not only receive data from the sensors and organs, it also delivers continuous forecasts to them: What should your sense organ – eye, ear, or fingertip – be feeling the next moment? What performance task should you deliver right now? If the forecast and the result match, everything is fine and there’s no need to think about it. "Processing continues only for the unpredicted things, the surprises," says Muckli.

There are three different ways that the brain then continues with its processing functions, depending, of course, on the size of the "surprise."

Renowned neuroscientist Moshe Bar, director of the Cognitive Neuroscience Lab at the Brain Research Center at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel and an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, calls it a "feed-forward method for top-down predictions." His explanation highlights the difference between this method and the one usually attributed to the brain: a more computer-like way of decision-making. Instead of "interpreting our world merely by analyzing incoming information," he says the brain is using "top-down guesses that are based on rudimentary input information." This is part of a never-ending story that leads from analogies to associations to predictions to new analogies and so on.

The brain, it seems, is extremely successful with this "feed-forward" process. So it is perhaps interesting to observe that nothing else seems to have made use of its model – that is to say, no one has really tried to replicate its success. None of the objects, institutions or systems built by men mirror the way the brain works in this idiosyncratic way. The top-down channels in companies are not used to predict the outcome of departments, teams or individuals over the following seconds or minutes. Instead, they are accustomed to giving orders and/or setting targets with much longer timescales, such as for the next quarter or fiscal year. The military and bureaucratic roots of management are still abundantly clear in both theory and practice, but they are not very neuroscientific management methods. It could be said they are not using an intelligent model.

So here's a little thought experiment. How would a brain go about managing a company if it were to use the same techniques and processes on that company that it uses to manage a body? Maybe it would be something like this:

This neuroscientific management scenario may sound like dictatorship at first with an all-knowing, almighty CEO setting the pace minute by minute and reaching out to employees immediately if things don’t go as planned. But this is not an intelligent way of thinking about it.

Our brains aren’t body dictators. In fact, they are quite the opposite. The heart, the eyes, the hands and so on – or, the parts of the company – just do their jobs without ever being disturbed by the brain. It is only in situations that go beyond the problem-solving capacities of the parts that the center has to step in and get involved in the process. The relationship between consciously processed information and incoming data (remember that ratio of 1:250,000) shows the high level of autonomy that could exist in a neuroscientifically managed company.

What kind of company would this suit best? The tiny time span of micro-forecasting would surely fit complex and data-rich industries: Logistics could be an example. It could also be well worth considering how a company could replicate the brain’s prediction abilities, looking at what data is required and how to assess it. While it could take a lot of brainpower to make a company work as efficiently as the brain, it could redefine the role of the CEO, turning it from one of chief into one of "cerebral executive officer" instead. Think about it.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/roland_berger_think_act_magazine_navigating_complexity_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

Don't miss our article with Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler, as well as much more food for thought.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.