Women in Africa

Women are driving economic growth, innovation, health and education in Africa. Learn more about how Africa's women are transforming the continent.

Taking a 94% pay cut to become director of a failing bank might sound crazy, but for James Mwangi, it wasn't about the money. Twenty-five years on and the Equity Group is proof that community can be the ultimate keystone of success.

Equity Towers has a commanding view over Kenya's capital, Nairobi. Here, on the ninth floor, is where you'll find the domain of the near-legendary chairman and CEO of the Equity Group, James Mwangi – the charismatic banker who turned a moribund microfinance company into Africa's largest bank. The office itself is spacious and well appointed with a large desk at one window, a row of trophies behind. Family photographs adorn the walls. The space has an intimate feeling of welcoming, almost understated luxury about it.

"Our colleagues in the industry ignored us ... We were snubbed because they considered us a village bank."

Equity is a real success story. Having started at the bottom of the pile, today it is now the top bank in East and Central Africa however you measure it: It's the largest bank by market capitalization, largest in Africa by customer base with 14 million at present and a target of 100 million by 2024 and it has won multiple awards both locally and internationally. It has also achieved something of a social revolution by bringing banking services to people who previously had little or no access to them. Yet despite being the man behind these not insignificant achievements, Mwangi has an easy, quiet confidence and a friendly welcoming mien. He looks like a man used to being at the top and winning. You might even think he was born to it. But his journey to these dizzying heights has hardly been conventional or easy.

These impressive offices are a universe away from the humble village in Central Kenya where he was born. His father died, leaving his mother to raise the family. Mwangi learned to pitch in to supplement the family's meager income. It was only with the help of the village community, who helped pay his fees, that he was able to go to primary school. Hard work and a government scholarship saw him through secondary, where he was introduced to commerce and accounting. It gave him a way to understand and organize his family's business activities. Looking back, it is easy to see that this ability to marry economic theory to the practical realities of village life led him to revolutionize the banking industry. As he puts it: "It's my background, it's my circumstances, it's my experiences that shaped the career that I pursued."

The country around him was being transformed as he grew up. Kenya's economy had been largely run by a tiny minority of mostly British and Indian settlers. Three British-owned banks dominated the banking industry and they ignored the African majority. After independence in 1963, the government promoted an Africanization of the economy, employed more Africans in the civil service and drove rapid economic growth through public investment. A growing African elite was thus able to access banking services – but most African families, such as Mwangi's, remained peasants, constrained to subsistence agriculture and casual employment. Banks continued to ignore them. And little had changed by the time he graduated from the University of Nairobi and embarked on his career, first at PricewaterhouseCoopers and Ernst & Young before moving on to Trade Bank where he quickly rose to the position of group financial controller within three years, becoming one of the most senior bankers in the country.

Rather than transactional relationships, Mwangi says he is seeking to brand Equity as "an anchor of the community."

But it had not all been plain sailing. As Mwangi was making his way to the top, indigenous banks were having a tough time. At independence, all but one were foreign owned. In the years that followed, the government established a number of banks but only one indigenous private commercial bank had been created by the close of the 1970s. The following decade would see the addition of seven locally owned banks and 33 non-bank financial institutions. Most were small and targeted the unbanked masses. Many were also poorly managed. Kenya had its first banking crisis in the mid-1980s and 12 of these institutions collapsed. A second wave of bank collapses in the early 1990s claimed 19 locally owned banks including a little-known building society set up a decade earlier and which had never turned a profit: Equity Building Society.

The Equity Building Society was established in 1984 to provide

financial services

to the mwananchi – the ordinary Kenyan. As Franca Ovadje described in her book Change Leadership in Developing Countries, the society "from inception … had a strong social mission. While profit was considered important, the founders were more concerned with contributing to the social and economic development of rural Kenya by providing the poor with access to financing." The bank initially did well. But after the tsunami of bank failures in 1993, a majority of Equity's loans were not being serviced and the company was in the red. Although it had nearly 3,000 accounts, three depositors accounted for 85% of the deposits. The Central Bank of Kenya declared it technically insolvent.

At the urging of one of the founders, Mwangi had invested his savings in the society in 1992 in a bid to keep an indigenous Kenyan institution afloat and because he felt personally invested in its management team. He watched with trepidation as it threatened to go under. In 1994, he decided to do something about it. He exchanged his cushy Trade Bank job for a directorship at the failing society and took a 94% pay cut. "My wife asked me how we [would] bring up a family on that income. I did not rationalize my decision … The cause spoke to my heart," he told Ovadje in 2011. He quickly recognized that Equity's heart was in the right place, but its model wasn't. Though it was giving out "mortgage loans," people were not using the money to buy housing. And the amounts were small and lent on a short-term basis. Mwangi recognized that Equity was actually in microfinance. Where others saw problems and despair, he saw the opportunity of a lifetime.

Mwangi does not come across as a reckless risk taker, and for him joining Equity was no gamble at all. The move could rather be described as the culmination of a life mission and the repayment of a debt. The people Equity was looking to serve were the same as those who backed him when he had nothing but his self-belief. Now it was his turn to back them. "I went into banking as a professional … but the opportunity of supporting my village to salvage Equity Building Society, which was failing, arose and that now demanded not managerial skills – there was nothing to manage – but entrepreneurial skills."

As a boy he had learnt to apply theoretical knowledge to the practical problem of turning a profit. Now, as the finance and operations director he brought to bear his considerable banking experience and training. "I brought professionalism into entrepreneurship," he says. He knew his customers in a visceral way – after all, he had been one of them. "I was among those who were excluded. My mother didn't have a bank account. No neighbor had a bank account. And so my vision was to build a bank for my mother. Success looked like banking for my mother. Success looked like banking for my neighbor." He figured that if he focused on the 96% of the population who, just like his mom and neighbors, had been ignored, then he wouldn't be competing against the other banks. His competition would be the domestic deposit bank otherwise known as "the mattress," under which many people stash their cash. But he also recognized that for his clients, having a bank account was about more than having a safe place to stash their incomes. Above all, it was about inclusion. For a population who had been sidelined, first by the colonials and then by their own government, having an account said their activity, their production, their ability and humanity were recognized and mattered. "It was a status symbol. It was an issue of esteem and dignity."

It was also a game of numbers. "I understood that profitability is a function of revenue and expenses and revenue is a function of price and quantity ... If we went with a model of large volume and low margin, we'd still be profitable … I also understood risk. If we disaggregated our loan book into small loans, I was avoiding risk concentration." The foreign-owned banks did not hide their disdain for this group, and as Mwangi was helping the Equity staff rediscover their original purpose and drive, the bigger banks were closing branches and getting rid of what they considered low-value depositors. As one Equity branch manager said of those early days: "Our colleagues in the industry ignored us … We were snubbed because they considered us a village bank."

Wanjeri Kihara, who worked at the bank from 2012 to 2014, says working at Equity was a culture shock for employees moving from other banks where the focus was on processes and structures. At Equity, it was all about the customer. That was reflected even in the choice of corporate color: brown, the color of the soil. "If you work at Equity, however senior you are, you have to relate with mashinani (the people at the grassroots) at the branches," she says, adding that staff were even advised against wearing bright clothing, because of the need to interact closely with farmers and traders who may come directly from their fields and shops. And Mwangi led the way. "He wears the gumboots," she says, referring to his impatience with protocol and eagerness to go directly to the branches and the customers.

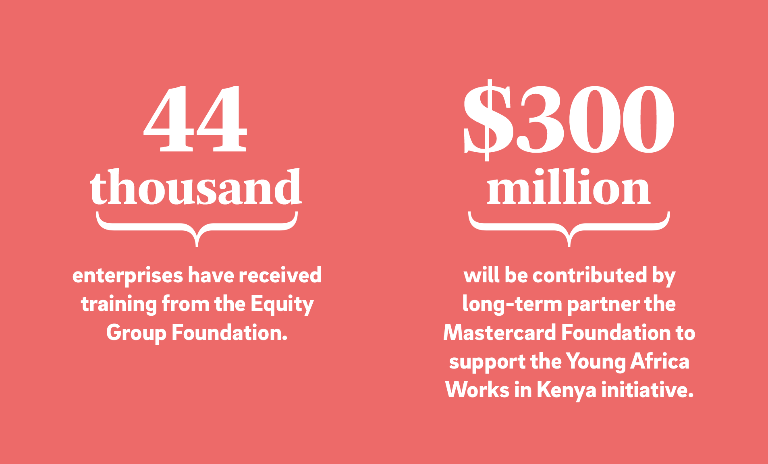

Named Person of the Year by Forbes Africa in 2012, James Mwangi took over directorship of Equity Building Society in 1994. Under his leadership, the bank has become the largest in East and Central Africa. His commitment to philanthropy and social work led to the establishment of the Equity Group Foundation in 2008 to enable access to gainful employment through skills development.

Garth Saloner of the Stanford Graduate School of Business first heard of Equity during a trip to East Africa with his students to learn about the microfinance community in Kenya and Uganda in 2006. They had intended to focus on NGOs and other nonprofits, but Equity's name kept coming up. There was no model for what Mwangi and his team had done, he says. "They completely set

out in a new strategic direction – one that was unproven." Though a lot of work had been done in microcredit in Bangladesh and in Asia, "the idea that you could build a for-profit organization around it at scale was very novel. That's difficult enough. But you also had a turnaround situation!"

The choice to focus on the bottom of the pyramid has been even more spectacularly validated by the astonishing growth of yet another corporate behemoth. By appealing to the same poor and undervalued customers when others targeted the wealthier segments of the population, mobile telephony provider Safaricom has grown into the largest company in East and Central Africa and is today perhaps Mwangi's biggest challenge. Three years after Mwangi converted Equity into a fully-fledged commercial bank in 2007, Safaricom launched M-Pesa, Africa's first mobile money platform. The service took off and within a decade it had near-universal adoption. That M-Pesa and the mobile financial services it heralded would pose a challenge to established banks, and Equity in particular, was clear from the onset. According to a recent study, "in 2008, only 25% of M-Pesa users were unbanked and 29% came from rural areas, a year later these figures were 50% and 41%, respectively." These were the very people that Mwangi was building his business on. Today M-Pesa has over 27.8 million customers and 148,000 agency outlets countrywide.

The bank explored several strategies in response, including a partnership with Safaricom. However, seeking more control over the experience that its customers will have when they access its mobile banking services, in 2014 Equity acquired its own mobile virtual network operator license, which has allowed it to create its own telecommunications infrastructure to deliver services over the phone. But Mwangi is already looking beyond Safaricom. "If asked who my true competition is," he says, "it is the big tech firms and the platforms … Facebook has jumped into the fray saying you can transfer money for free instantly using Libra." As it has done over the last 30 years, Equity will have to evolve. "It has to adapt to the environment in which it is operating. At the moment I would call Equity substantially a virtual bank, using mobile infrastructure to deliver services, having digitalized its back end. The future of Equity might require migrating towards a big tech and, who knows, eventually becoming a platform."

Providing services to the lowest strata of society remains Mwangi's focus. Despite the massive improvements in financial inclusion over the last three decades, the need remains great. Just 56% of Kenyans over 15 have an account at a formal financial institution compared with 93% in the US. And, although Equity today draws much of its revenue from the 21% of its customers that are large corporates as well as small and medium-sized enterprises, Mwangi is quick to add that most of these have come up through the Equity ecosystem. Equity is not looking to attract wealthy corporate firms, he says. "We are a long-term investor … The focus should be on investing, not extraction."

After 26 years at the helm of Equity, Mwangi is in no hurry to step down. He points out that his role model, the billionaire US business magnate and philanthropist Warren Buffet, is still CEO at 87. "By comparison, I still have another 30 years of service," he says. Equity recently appointed a new CEO for its Kenya operation allowing Mwangi to focus more on his dual role overseeing the Equity Group, which has recently extended its banking operations to eight countries in the region, as well as the philanthropic Equity Group Foundation.

Mwangi calls it "the social engine" of Equity's brand, complementing its "economic engine," the bank itself. As the nature of banking changes, it becomes more transactional and experiential – and less dependent on the emotional bonds of trust that have underpinned its success. The foundation is about helping Equity keep its relationship with communities. Rather than transactional relationships with individuals, Mwangi says he is seeking to brand Equity as "an anchor of community." And looking around his office, it all seems to make sense. For the boy who dreamed of being a teacher but conquered the financial world, and the billionaire entrepreneur who talks of reforming capitalism and reducing inequality, it has always been about family and community; about opening up the world to his mother and her neighbors. And about repaying the investment they made in him half a century ago.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/Think_Act_Magazine_Darwinism_Cover_EN_download_preview.jpg)

Change. Survive. Thrive. What your company needs to know to prosper in the digital age.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.