The purpose principle

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/think_act_magazine_purpose_the_purpose_principle_cover_1_download_preview.png)

What does purpose mean to you and your business? Our Think:Act magazine on purpose addresses changing values in the business world.

by Detlef Gürtler

illustrations by Olaf Hajek

Read more about the topic

"The purpose principle – missions give businesses strength"

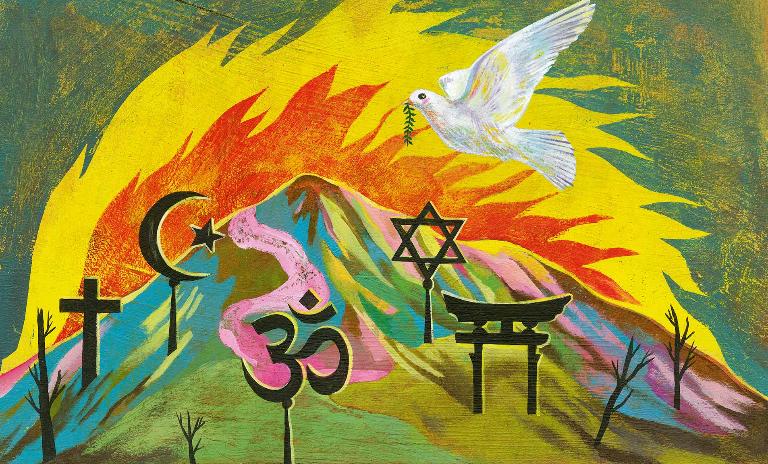

Praying to God alone is unlikely to change the fortunes of your business, but the sense of purpose and other values embedded in various religions can be a dynamic, if not a spiritual, force for good – and they may even provide a competitive advantage.

When the Japanese economy outshone the rest of the world in the late 1980s, an almost heretical thought was muttered throughout the (Christian) West: Could it possibly be that the Japanese religion, Shintoism, was a reason for the country's economic superiority? Not that European or US managers would ever want to build a shrine for their company god or make their whole workforce worship every morning, but if religion really were a key element in Japan's success, the country's economic dominance would be here to stay.

Whatever part Shintoism played in Japan's business boom – or didn't, as the case may be – it is still worth posing the question: Does religion matter? One of the hottest debates regarding the significance of religion for economic development was started in 1904 by Max Weber. The German sociologist argued that the Protestant work ethic was an important factor for the birth of capitalism in Northern Europe. The Calvinist branch of Protestantism in particular believes that individual economic success on Earth is blessed by God. Work is like a prayer, investment is like worship – and that's the mindset that kick-started capitalism.

Weber's thesis that religion matters became one of the most influential (and most quoted) papers in social sciences and has been heavily discussed ever since. Indeed there's a correlation: The oldest capitalistic region in the world, England, is predominantly Protestant; in some countries, such as Switzerland or France, the Protestants were especially thrifty and attracted to business; and the economic rise of the United States of America was driven for the most part by Protestant immigrants from Europe.

"Work is like a prayer, investment is like worship – and that's the mindset that kickstarted capitalism."

But correlation does not necessarily mean causation. In 2015, 111 years after Weber, another German economist named Ludger Wößmann found compelling evidence for an underlying effect that caused the Protestant "economic miracle": education. The belief that every Christian should be able to read the Bible for himself led to an education boom and improved literacy across all Protestant regions. Martin Luther even favored schools for girls – an incredibly progressive idea for 16th-century Europe. This pro-education bias became a competitive advantage: The data Wößmann analyzed from 19th-century Prussia showed a much higher level of education in Protestant than in Catholic regions. In addition, the Protestants had higher incomes and were more likely to work in modern sectors of the Prussian economy, such as commerce.

Another example for the long-term economic effects of education can be studied in Judaism, which enforced a religious norm requiring fathers to educate their sons from the end of the 2nd century AD. Economists Maristella Botticini and Zvi Eckstein are convinced that this had a major influence on Jewish economic and demographic history in the first millennium: "The Jewish farmers who invested in education gained the comparative advantage and incentive to enter skilled occupations during the urbanization in the Abbasid empire in the Near East and they did select themselves into these occupations." And as merchants the Jews invested even more in education – literacy and numeracy are the key preconditions for building up trading networks.

If the decisive factor for the economic success of believers is not the belief itself, but the appetite for education, the trophy for the most economically successful religion can change hands. A 2016 study by Pew Research Center on religion and education around the world saw Judaism in a strong lead (with more than 13 years of schooling on average) followed by Christians (nine years), Buddhists (eight years) and Muslims and Hindus (both with less than six years). In the younger generation, however, Buddhists have reached almost the same schooling level as Christians.

This picture can look very different if you focus on a specific region instead of the whole world. In the US at the start of the 21st century, for example, the world religion with the highest quota of college graduates were Hindus: 67% had gotten (at least) a college degree. They were followed by Jews, Muslims and Buddhists, all of them still above the US average of 33%. Far below average were the college degree quotas of Christian niche beliefs such as Baptists or Jehovah's Witnesses. With education as an early indicator for economic trends, a shift of economic success is predictable: from predominantly Christian countries to regions with a high number of Buddhists and Hindus.

"A shift of economic success is predictable: from predominantly Christian countries to regions with a high number of Buddhists and Hindus."

In history, though, religion has not always settled for peaceful competition. There are wellknown episodes showing a strong combination of religion and success – namely military. The Muslim expansion all around the Mediterranean from the 7th to 9th century AD was mainly driven by religious zeal, just like the crusades of the Middle Ages or the conquests of South America in the 16th century: The Holy Cross of Santiago promised victory (not to mention gold) to the Spanish adventurers. "The expansionary element is not typical for all religions," says the German anthropologist Dieter Haller. He sees it as a feature of religions that define themselves as approaching an ideal or paradise, like Islam or Christianity: "This kind of teleologic or goal-driven thinking is dynamizing moral behavior and economic action. But you get completely different dynamics if a religion, like Buddhism, does not strive for an ideal, but sees life as an alienation from this ideal." So the difference between "paradise" and " nirvana" is more than just religious: A Buddhist conqueror would fight his battles not for his religion, but in spite of it.

In business, religion can also be a dynamizing factor. There are a lot of entrepreneurs who identify themselves with a religion – from the Catholic Brenninkmejier family running the C&A retail chain to Islamic banking or real estate agents with links to Scientology. As with military success stories, business cases linked to a religious attitude often take place in an early stage of expansion: The unifying effect of one strong belief can lead to a more coherent, focused, motivated workforce and can be a decisive factor in beating the competition as the company represents more than just an opportunity to earn money.

Devdutt Pattanaik, an Indian leadership expert and former "Chief Belief Officer" of a large Indian retail chain, even calls for a mythologization of companies. For him, a mythology is something that "tells people how they should see the world" – something a company with a strong mission can offer its employees. "When institutional beliefs and individual beliefs are congruent, harmony is the resultant corporate climate," Pattanaik says. He doesn't recommend the leaders to brainwash their staff, however. Quite the contrary: "When people are treated like switches in a circuit board, that's when disharmony descends."

There is a thin line between harmony and polarization whenever religion enters into secular affairs. What looks like heaven on earth when the beliefs of the workforce are homogenous can turn into a hell of a nightmare as soon as employees and/or management belong to different religions. This increase in diversity will definitely happen when a company starts to grow beyond the cultural sphere of its origin – and then it's too late to take religion, faith and/or mythology out of a company's DNA. So even if religion can be a driver of growth for smaller companies, it will be more like a limit of growth for bigger ones. Keeping the faith isn't as simple as it sounds.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/think_act_magazine_purpose_the_purpose_principle_cover_1_download_preview.png)

What does purpose mean to you and your business? Our Think:Act magazine on purpose addresses changing values in the business world.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.