The Inflation Reduction Act introduces several measures to regulate drug pricing. So what are they and what are their implications?

The era of free drug-pricing in the US has come to an end

By Filip Conic

Update on steep discounts announced by CMS in August 2024

The Inflation Reduction Act (P.L. 117-169) requires the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS, the price-regulation body) to negotiate the prices of certain high-cost drugs covered under Medicare Part D, the prescription drug benefit for over 65s. The goal is to achieve a "Maximum Fair Price" (MFP) ceiling. Prior to the IRA, retail drug prices in Medicare were determined through negotiations between private entities, with manufacturers often offering rebates to Medicare (and Medicaid) almost as a gesture of goodwill to secure placement on their formularies.

Now, for the first time, the IRA gives CMS the ability to negotiate directly with drug manufacturers for an MFP for brand-name drugs that have the highest total expenditures under Part D. Such drugs must also not be plasma-derived, not have generic substitutions, have more than one indication (or if one, not an orphan indication), and at least seven years (for small molecules) or 11 years (for biological products) must have elapsed between the FDA date of approval and the selected drug publication date.

From the industry perspective, the implementation of this pricing scheme will likely have a negative spillover effect across the broader pharmaceutical market, particularly affecting private plans that administer Medicare Part D. The lower negotiated prices could set new benchmarks that private insurers might adopt in their negotiations for drug prices. As a result, the impact of these discounts will not be confined to the 36% of the market made up by public health insurance; instead, it could reshape cost expectations across the entire pharmaceutical market in the U.S.

Are skyrocketing discounts becoming the new name of the game?

Starting in 2026, the MFP negotiation provision will initially apply to 10 specific drugs. The MFP is defined as the lower of either the net price paid by Part D plans in 2022 or the non-federal average manufacturer price, adjusted for the time since the drug's approval by the FDA. On August 15, 2024, CMS published the negotiated prices for these drugs, including the percentage discount from the retail price, giving an indication of the savings CMS aims to achieve through negotiation. The drugs chosen in this round are used to treat common conditions like diabetes, inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, and cardiac and kidney disorders. So far, only one anti-cancer drug was selected.

At this point, the final prices are clear, but the methodology behind them, including the previously paid net prices under Medicare Part D and the comparators used, is a black box. When CMS negotiates drug prices, it considers the net prices of alternatives as a starting point. But without access to these net prices, it's hard to know exactly how much of a discount Medicare is really getting, or the baseline from which negotiations start.

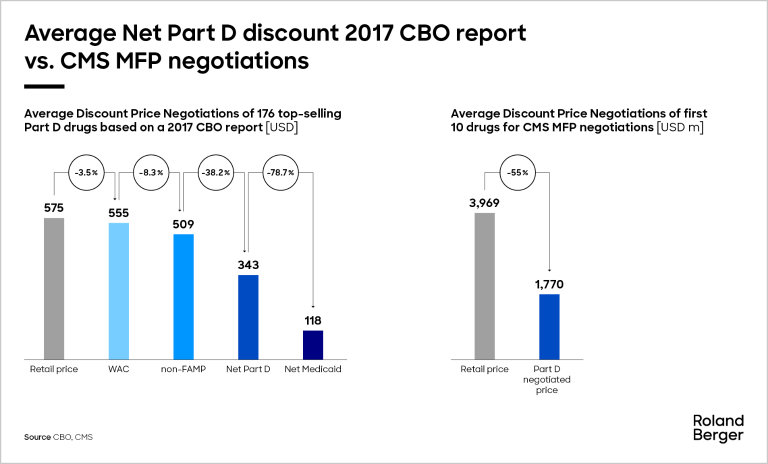

Historically, manufacturers have often provided significant rebates to Medicare Part D plans, but these net prices were not publicly disclosed. Nevertheless, according to a 2017 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report, the average net price for Medicare Part D drugs was about 40-45% below the retail price. This report, although presenting the data in an aggregated form and being somewhat outdated (2017), remains a key reference point because it was the last time the CBO published data on net prices. The net price paid by Part D plans was one of the factors CMS considered when setting the new MFPs.

The discounts CMS has now negotiated for 2026 under the IRA appear much steeper, with seven of the 10 drugs receiving discounts of between 60% and 80% off the 2023 retail price. The CMS discounts published by the CBO in 2017 demonstrate that the new CMS-negotiated prices today are considerably lower than what was previously attainable through typical negotiation mechanisms. It remains to be seen whether CMS' rationale for the MFP calculation will be published according to the initial announcement.

What’s coming next?

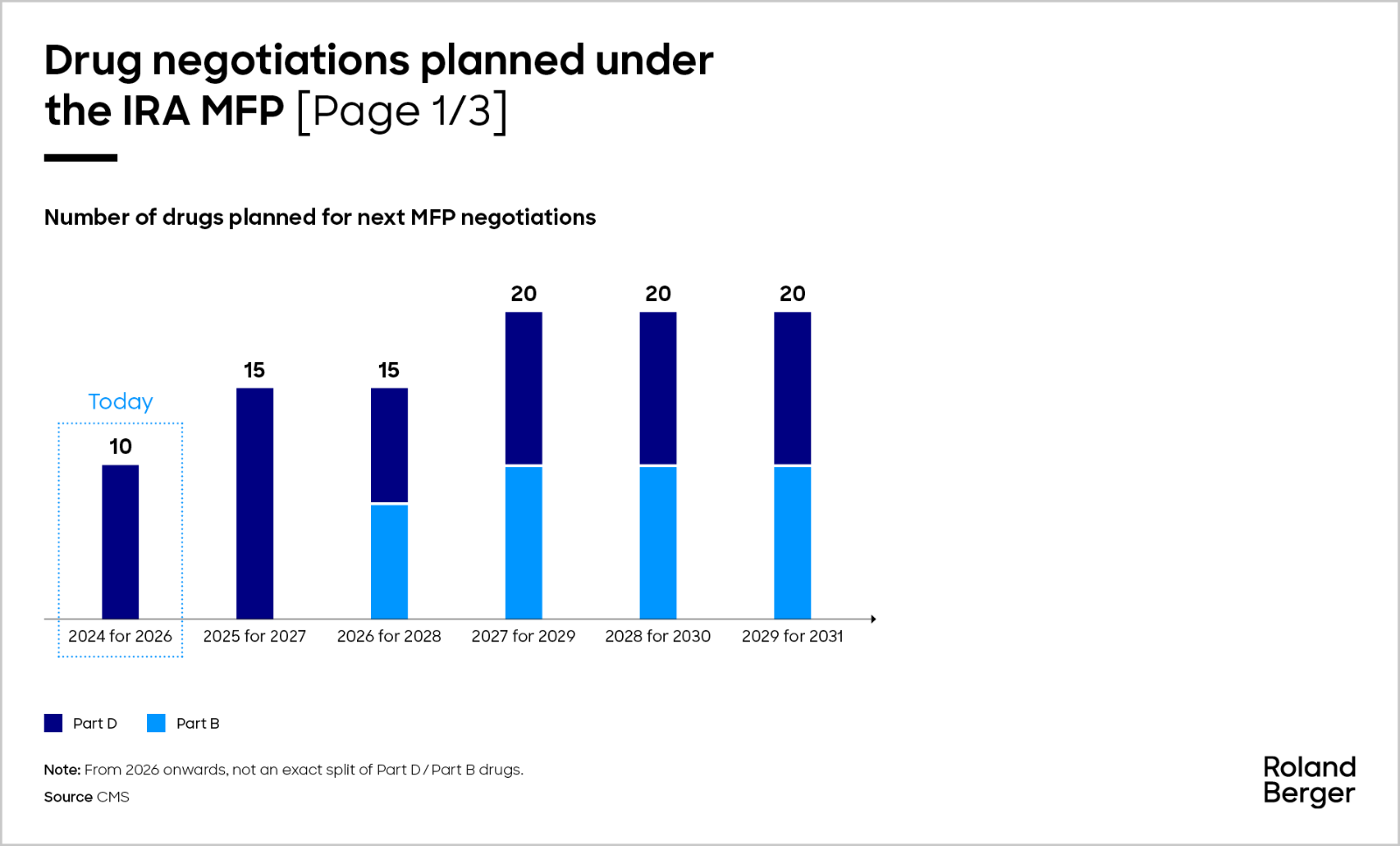

The number of drugs subject to MFP negotiation will increase over the next few years. CMS will select up to 15 more drugs covered under Part D for negotiation for 2027 by February 1, 2025, followed by another 15 in 2026 made up of Part B and Part D drugs, and then another 20 drugs under Part B or Part D for the later years, accumulating over time. By applying the criteria of annual Medicare spend above USD 200 m (2022 proxy) alongside the others as previously described, we anticipate that the following molecules will potentially undergo price negotiations in 2025.

In the third cycle in 2026, CMS will select up to 15 more drugs covered by Part B or Part D for 2028, and up to 20 more Part B or Part D drugs for each year after that. According to the MFP eligibility criteria, out of all Part B drug spending in 2022, there are only 10 drugs that we believe would qualify for negotiations, making up 10% of total Medicare Part B 2022 spend.

"Not only will the prices of drugs selected for CMS negotiation face increased scrutiny, but companies planning to launch products in the increasingly crowded oncology, gastrointestinal, and respiratory markets should also prepare for a new reality where pricing potential may significantly diminish."

Unlike the Medicare Part D list, most of these molecules are biologics, which are typically more expensive and complex to produce but have lower Medicare spending compared to the Part D list. Therefore, negotiations targeting these drugs may not involve as steep a revenue loss for manufacturers as seen with Part D drugs. However, because these drugs are more specialized, the impact on revenue could be concentrated in specific patient groups and healthcare providers, unlike Part D drugs with more widespread use. The therapeutic areas most affected by these two lists are respiratory, gastroenterology, oncology, and hematology.

Given the anticipated new launches in these therapeutic areas, it remains to be seen whether the general price level will decrease, or which approaches manufacturers will deploy to justify the therapeutic value of these novel medicines. In light of deteriorating pricing potential, the manufacturers still may decide not to enroll, as the Part D program is generally voluntary. Nevertheless, if a manufacturer does not want to participate, they will be charged an excise tax starting at 65% of product sales in the U.S., increasing by 10% every quarter to a maximum 95%. Alternatively, manufacturers could choose to withdraw all of their drugs from the Medicare/Medicaid programs.

Apart from large international manufacturers affected by the new regulation, it's also important to recognize the potential risks associated with the small biotech exemption. Currently, four drugs qualify for this exemption based on strict criteria: the drug's expenditures under Part D must be ≤1% of the total Part D expenditures, and the drug must account for ≥80% of the manufacturer's total Part D expenditures under a coverage gap discount program agreement during the same year. As the landscape of drug pricing changes, small biotech companies may find it increasingly challenging to meet these criteria as their drugs gain market share or as policy shifts narrow the scope of eligibility, leading to small biotech drugs being subject to the same steep discounts as larger competitors.

What’s the next big thing?

The upcoming U.S. presidential election on November 5, 2024 bears significant implications for the IRA. Vice President Harris, the current Democratic presidential nominee, cast the tie-breaking vote for the IRA in the Senate in 2022, a key part of the Biden-Harris Administration's Investing in America Agenda. Should the Democrats retain power, we can expect an acceleration of dynamics related to the IRA. Conversely, if former President Trump, the Republican nominee, is elected, the rollout of price negotiations could be slowed or even altered. As a matter of fact, no Republican in the Senate or House has previously voted for the IRA. Project 2025 outlining the second Trump term calls for the repeal of the IRA.

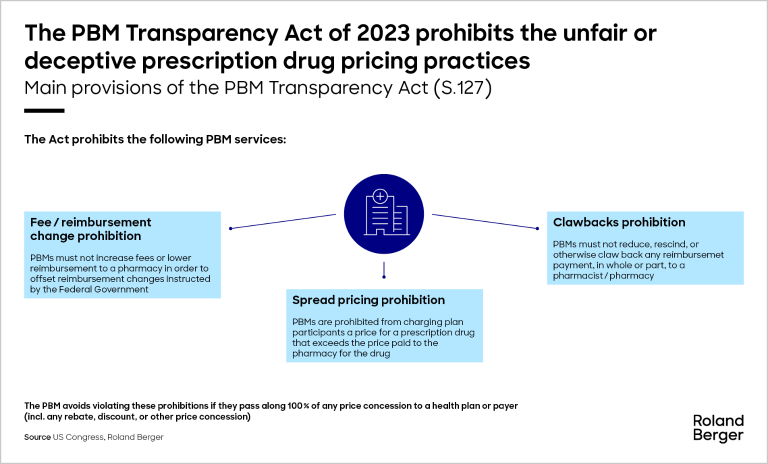

Additionally, Republicans are likely to focus on reforming pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), the intermediaries that negotiate prices between drug manufacturers and insurance companies. The bipartisan Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act introduced in 2023 directs the Federal Trade Commission to increase transparency of PBM practices and end spread pricing and the clawback of reimbursement payments.

The IRA marks the most substantial shift in U.S. healthcare policy since Medicare Part D was introduced nearly two decades ago. However, tackling the influence of PBMs could bring about an even greater transformation, as PBMs play a central role in the entire drug pricing and distribution system.

Planning ahead and preparing future pricing of your assets

As we look ahead to future price negotiations, it is crucial to be prepared for the next batch of drugs. While we still do not fully understand the precise methodology behind the derived prices, it's clear that the trend toward steep discounts, ranging from 60% to 80% off the list price, is evident and could significantly impact revenue streams. Therefore, pharmaceutical manufacturers must urgently take steps to prepare for the next round of price negotiations:

Comparator analysis

- Estimate the net prices and/or ASPs of Part D and Part B therapeutic alternatives that could serve as price benchmarks in future negotiations

- Develop multiple viable pricing scenarios and fallback options based on levels of anticipated CMS-negotiated discounts

Strategic spillover estimates

- Quantify potential spillover effects of CMS-negotiated prices onto private insurance plans

- Mitigate pricing leaks stemming from international reference pricing – so far, only a few countries reference the U.S. (e.g., Japan and Brazil), but it remains to be seen if more countries will adjust their pricing reference baskets, and to which price point (WAC vs. negotiated CMS price)

Evidence generation plans for negotiation strategy development

- Prepare strong (real-world) evidence commitments on the clinical benefits compared to therapeutic alternatives, particularly in meeting unmet medical need and impact on specific populations, for the purpose of adjusting the starting point used in negotiation factors

_image_caption_none.png)

_image_caption_w1280.png)

_image_caption_w1280.png)