Journey to the future

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta39_en_covers_1_final_download_preview.jpg)

What if we could journey to the future to gain insights for 2050 and beyond? Think:Act gives you a playbook for the future to adapt, survive and thrive.

by Detlef Gürtler

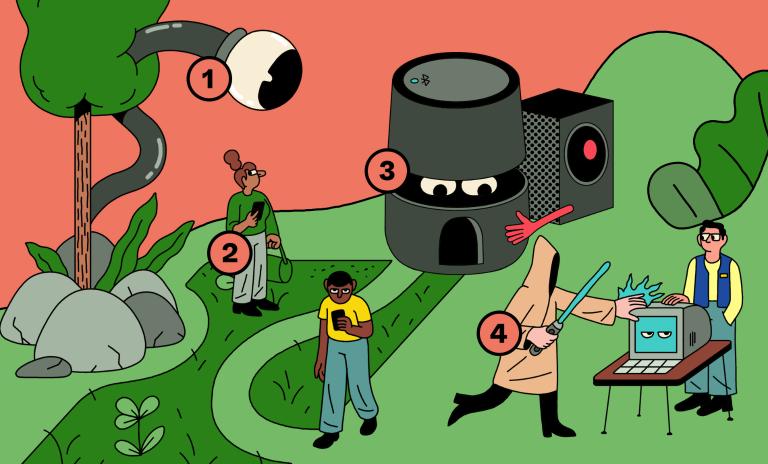

Illustrations by Simon Landrein

Imagined futures portrayed through the eyes of artists have a huge influence on how we envision what could be. Some have even gone on to inspire scientists to reshape our reality.

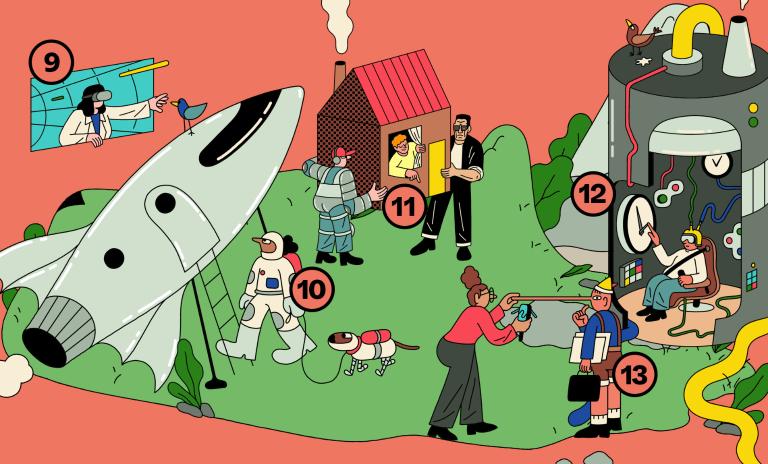

Did you ever hear of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky? Probably not. He’s the Russian physicist who died in 1935. Even if you’ve never heard of him, you will certainly know one product that was developed – mostly after his death – and which relied heavily on his findings: the rocket. Alongside scientists such as the German Hermann Oberth and the American Robert Goddard, Tsiolkovsky is seen as one of the founding fathers of rocket science and astronautics.

And even though you may have never heard of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, you also will certainly know the source of inspiration that propelled him to become a rocket scientist in the 1870s: From the Earth to the Moon, a novel by French science fiction author Jules Verne. In it, Verne describes how three men are shot to the moon with an enormous space cannon – and the teenage Tsiolkovsky, who was not allowed to go to school because he was deaf, read the book, thought that a cannon could in no way be a tool for traveling into space and started to think about other ways of getting to the moon. And, at last, found one.

Would we have reached the moon without this one deaf Russian scientist? Possibly – there had been others around at that time who also thought about space travel. But would we have reached the moon without this one science fiction novel? Not so sure. Jules Verne gave us an idea of how our future might look like; a powerful vision, giving scientists’ brains something to chew on, something to start with.

Jules Verne is not the only writer whose fiction became fact. And scientists are not the only ones to be inspired by imaginative literature. Just take two of today’s most famous innovations. Mark Zuckerberg’s Metaverse is by name and concept a copy of the virtual dreamworld in Neal Stephenson’s novel Snow Crash, with the one exception that in the original Metaverse from 1992, the avatars have legs. For Neuralink, a company co-founded by Elon Musk in 2016 to produce brain-machine interfaces, the concept is 100% identical with a technology described by the Scottish science fiction author Iain M. Banks in his novels of the Culture series. The name, though, is slightly different: Banks called it “neural lace.”

"We shall one day travel to the moon, the planets and the stars, with the same facility, rapidity and certainty as we now make the voyage from Liverpool to New York!"

Artistic stories about an imaginary future are an important component of the creation of the future in our real world. And that’s not because the artists are clairvoyants who know centuries in advance where technology is heading. It’s because their imaginations are sticky: They give a vision of what future technology might look like – and once you’ve seen it, you can’t unsee it. The kind of influence fiction has on real-world development is fourfold: It influences children, creators, decision-makers and customers. For children, it’s a source of inspiration for their career choice. Like the young Konstantin Tsiolkovsky who became motivated to create rockets, children can be inspired by novels or TV series to become scientists or engineers. And wherever their career leads them to, they will never forget what made them tick in the first place.

For creators, the influence is creative: Let’s face it, the imaginative powers of engineers or scientists are limited. They have learned how to make machines, or how to research. But how to envision a future no one has ever been to is not part of their job description. If someone does that for them, their work gets some kind of orientation. That influence extends to investment decisions becoming easier: It doesn’t matter whether you are a banker, a venture capitalist or a CEO, it’s a challenge to decide which new developments you should invest in. But if its features or its description match with an image you already know, decision-making becomes easier. “Wireless earphones with near simultaneous translation capacity” is harder to swallow than “a babel fish device.” Whoever read Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and millions of people have, knows instantly what is meant.

Finally, customers need fewer explanations: It’s a demanding task to launch a completely new product. No one knows it, no one has ever seen or used it – you’re going to have a lot of (expensive) explaining to do. That’s why smart home technology is often advertised with magic-mirror-like gadgets, taking their cue from the Brothers Grimm and their “mirror mirror on the wall” fairy tales; and why 3D printers often get connected with the “replicator” machine made famous by Star Trek.

The better known a work of fiction is and the wider reach it has, the greater the stickiness. No wonder that Star Trek is one of the leading sources for real-world creations: The Holodeck and holograms, 3D chess and the replicator, “phaser” guns and “beaming” teleportation have all inspired children to become engineers – and engineers to build futures. The teleportation, though, has only as yet reached single-atom level. Whether humans can ever be beamed like Kirk and Spock remains to be seen.

So should we just hire science fiction authors for our product development department so that they can envision what our future product portfolio might look like? Unfortunately, it’s not that easy. That’s what the high-flying augmented reality startup Magic Leap learned the hard way. In 2014 they hired the Metaverse inventor Neal Stephenson as “Chief Futurist.” He promised “to continue working on the sorts of transmedia projects that I have been interested in for many years.” Magic Leap’s performance however was severely underwhelming – and in 2020, when the company had to fire half of its employees, Stephenson also had to go without leaving significant traces at Magic Leap.

Hear the sounds of the future from artists past and present:

One of those authors – Tom Hillenbrand, the Munich-based creator of sci-fi novels like Drone State (2018, English translation) or Montecrypto (2023, English translation) – says: “Authors do not know more about the future than other people. It is not our intention to make predictions about the future. Science fiction is always more of a commentary on the present from a future perspective.”

In Drone State, which was first published 2014, Hillenbrand envisioned a country that tries to prevent crime with 100% surveillance via cameras and drones. But then, a politician is killed and the near omniscient police computer screws up – the killers have learned how to beat the digital system. “Drone State has become reality more quickly than I would have expected,” Hillenbrand says today. When he wrote the book, he thought that crime prevention via digital surveillance would need at least a few decades to become technologically and politically feasible – but “China is already almost there.”

When he thinks about a future, it’s not about product design. It’s about people. What happens to free will in times of omniscient technology? What do you do when death can be reversed? What happens to love when genetically perfect matches can be defined? The stuff around those basic questions is more metaphorical: “Terminator uses the killer robot to point out the dangers of artificial intelligence. But of course you could also use other, less apocalyptic metaphors.”

The power of science fiction is not the literal translation of imagined tech into real-life tech. It’s the openness for the unknown, says Hillenbrand and quotes the US sci-fi writer Ursula Le Guin: “You can read science fiction as a thought experiment.” The fiction is a kind of laboratory where anything can be tried out and anything is possible because it’s in the future. And that’s, indeed, where science fiction can become productive for corporations. The artist’s vision of a future where no man has gone before can open up business-focused minds and entice them into a trip to uncharted territories. It’s a kind of disruptive experience that is used by global players like Volkswagen or Intel – though more as a spice than as an ingredient of their business strategies.

There’s just one industry that has regular long-lasting business relationships with science fiction authors: futurists and trend researchers. When your main job is to think about “the future of xyz,” whatever that xyz may be, the disruptive creativity of science fiction is probably one of the ingredients of your secret sauce. Science fiction author Marcus Hammerschmitt has been a long-time contributor for the Swiss trend researcher Gottlieb Duttweiler Institute. For him, “one crazy question” is at the heart of the development of a story. That question could be something like “what does a society look like where you are born in debt and have to work your whole life to pay it back?” or “how do you compete when there’s no more scarcity?” In Hammerschmitt’s writings, each book is an endeavor to answer one question. In his contributions to trend research, these questions are more like a bridgehead to the unknown side of the river and tempt the trend researchers to imagine what the bridge from today’s reality to that other side could look like.

Today’s mostly gloomy future visions, however, make “temptation” perhaps sound a bit too bright. Ancient and medieval myths dreamt of an end of ever-looming hardships: Fountain of Youth stories and never-ending paradises had magic potions and golden egg-laying geese to overcome scarcity. It was a long way from ever becoming reality, but the images became part of folk culture. Then came the industrial age and everything became possible – the dreams went from ending scarcity to creating technology. From Jules Verne to Douglas Adams, from Star Trek to Star Wars, all assumed that a sci-fi future would provide a (more or less) good life. Since the 1980s, the picture has become darker. Cyberpunk entered the stage, with William Gibson’s Neuromancer as a frontrunner in 1984. The future is not necessarily something to hope for, it can be just the opposite. Stuff like Mad Max, Black Mirror or Squid Game is still around as a kind of background music for civilizational clashes and climate conundrums – more a lab for new ways of survival than for new technologies. All of which provides us with something to think about.

So where can we turn to get back into future inspirations? The Austrian tech philosopher Peter Glaser recommends to look at the oldest sci-fi texts we know: stories of myth and religion. They are full of wonders and magic – and isn’t technology a little like magic? “Healing the lame, feeding the world and reviving the dead: That’s what Jesus Christ did 2,000 years ago and that’s what humans can aim at,” Glaser says. And it’s not just the Christian religion that is full of wonders. Just take the ancient Greeks as an example: Their gods could calm the storm, send rain or sun and save the harvest. Those are some powers that we could really use quite soon.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta39_en_covers_1_final_download_preview.jpg)

What if we could journey to the future to gain insights for 2050 and beyond? Think:Act gives you a playbook for the future to adapt, survive and thrive.