Cargo drones: The future of parcel delivery

By Stephan Baur and Manfred Hader

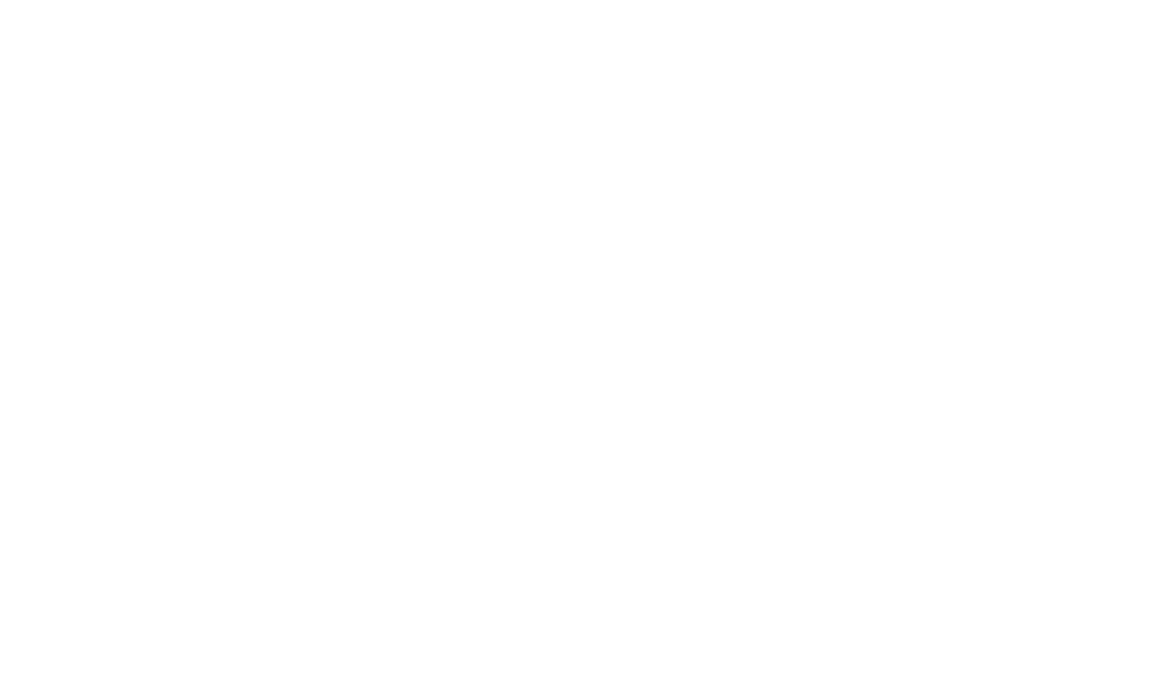

USD 5.5 billion market volume for non-military drones globally

When it comes to non-military applications, the logistics industry is blazing a trail in the use of unmanned aerial vehicles. In this article, we look at both current and potential use cases of cargo drones, and why the parcel delivery sector in particular is shaping the future of UAV applications.

The race to develop passenger drones has undoubtedly captured the public’s imagination over the past years. Few would disagree that the idea of hailing a flying taxi appeals to both our sense of fun and convenience, as outlined in the recent Roland Berger report on Urban Air Mobility. Yet it’s in the rather less glamorous logistics sector where real, practical progress is being made in the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Unlike flying taxis, cargo drones are a proven technology – they can now drop online shopping deliveries in back yards, deliver vital medicines to otherwise inaccessible locations and zip around warehouses delivering parts at the precise moment they’re needed.

In this article, we argue that one sector in particular – parcel delivery – will shape the future development of cargo drone use cases and other UAV applications. We expand this argument in a forthcoming second article which outlines how a city-wide UAV parcel delivery system might work, using the city of Berlin as an example.

The civil UAV market

Most people are still largely unaware of the applications of non-military drones. But that will soon change. Civil UAVs will become as commonplace as delivery vans and taxis in the not too distant future, with players from different industries battling it out for air space.

The civil UAV market can be split into three categories: infrastructure inspection and maintenance; environment inspection and maintenance; and transportation and leisure, which includes cargo drones (see graphic below).

Each category has the potential to radically change or simplify the conventional way of carrying out tasks and interacting with three-dimensional spaces. Indeed, many applications, especially in the inspection and maintenance fields, are already well-developed, creating sub-industries for hardware, software and service providers.

As a result, the civil UAV market is booming . It had a global volume of about USD 5.5 bn in 2019, and the market for production and services applications is forecasted to grow at around 11% per annum over the next five to six years, largely driven by the infrastructure sector. This suggests a valuation of around USD 10 bn by 2025.

At the moment, production accounts for about two thirds of the market, while services account for only a third. But in time, UAV hardware will become more affordable and value-added services will start to gain a much larger portion of the market. It is expected they will make up more than half by 2050.

Logistics takes off

Today, it is the logistics industry, and not the Urban Air Mobility sector, that leads the way in already-operational UAV use cases. This is largely thanks to the growing number of national authorities that have issued permits allowing companies to trial commercial cargo drones, led by pioneers such as Australia, Singapore, Iceland and Switzerland. These usually involve firms being allowed to operate fee-charging UAV services at certain times, and surveying customers afterwards to improve their offering.

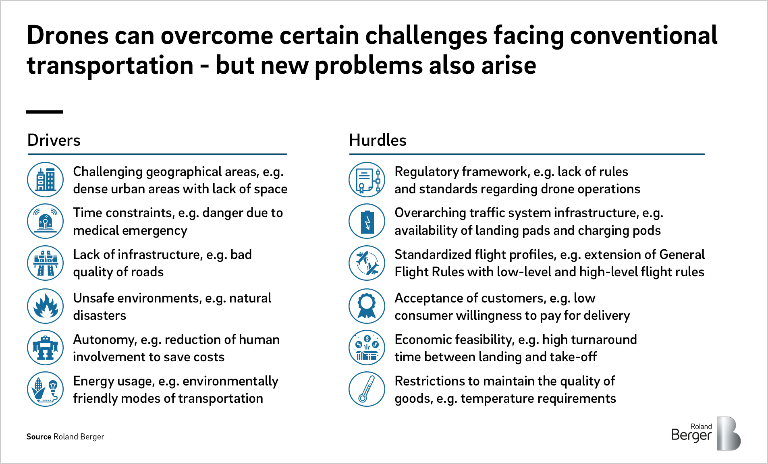

Currently, there are four different cargo drone use cases, in varying states of implementation: automation of intralogistics, covering factories and warehouses; parcel delivery (first/last mile), catering to dense urban areas; supply of medical goods, normally to hard-to-reach places; and transportation of air freight, usually in rural areas.

Each aims to automate the transportation of goods while offering faster, more flexible, less expensive and more environmentally friendly service than the alternative. But an important question for players in the industry is which will be first to dominate the air space and set the pace and regulatory framework for the others. To answer it, we first need to look at each use case and some examples in more detail.

Key cargo drone use cases

Automation of intralogistics

Manufacturing processes often depend on just-in-sequence delivery of materials. In order to ensure the availability of the right material at the right time, indoor drones can be deployed to deliver single items directly to the production line. Carmaker Audi, for example, is currently piloting an indoor drone at its Ingolstadt plant. Navigating via sensors, it autonomously transports automotive parts up to 2.0 kg in weight directly to the required step in the manufacturing process. The drone can travel at up to 8 km/h.

Parcel delivery (first/last mile)

For logistics companies, the first and last mile constitute the most expensive and least efficient part of a delivery, requiring significant manpower, vehicle numbers and time. They therefore view it as ripe for automation.

Wing, the cargo drone specialist owned by Google-parent Alphabet, achieved a breakthrough in this respect in April 2019. It was awarded the first ever U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) air carrier certificate licensing unlimited commercial deliveries using cargo drones. The license made no restrictions on flights over crowds or urban areas – the first time this had been granted outside a pilot project.

The decision gave Google a crucial advantage over its US rivals – Amazon, which has enjoyed success with its Prime Air drone service in Britain, had been working to get a similar license in the US for years. To date, only one competitor has come close: In October 2019, courier UPS and drone company Matternet announced they had received FAA approval for their on-demand drone deliveries of medical supplies to hospitals. The service became the first drone airline with an operating license for the whole country.

Meanwhile, in March 2018, China-based logistics giant SF Express became the first company to be issued with a commercial license for last mile parcel delivery by the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) . Domestic rival JD.com soon received a similar license, and it has now completed government-approved deliveries of more than 250km between islands in Indonesia, overcoming previously insurmountable boundaries and distances.

Supply of medical goods

For many patients, fast and reliable transportation of medical goods is of life-saving importance. Cargo UAVs can rally make a difference here, especially in rural areas, and several ideas are being tested. In late 2018, DHL launched its "Parcelcopter 4.0" pilot project in Tanzania, using a drone made by Wingcopter. It can fly at up to 130 km/h and has a maximum flight time of 40 minutes, enabling it to deliver up to 4kg of medical supplies over 65km.

Similarly, Silicon Valley start-up Zipline has been operating a medical supply drone service to 25 hospitals and clinics in Rwanda since 2014. In this time, it has delivered more than 16,000 packages on demand, primarily blood samples and blood products. Medical goods can be ordered via cell phone and drones can be launched in just 10 minutes, providing a life-saving alternative to slow and difficult overland journeys. The service now also operates in Ghana, and a pilot program run by the FAA is planned in North Carolina.

Transportation of air freight

High capacity and long-range deliveries via cargo drones are becoming increasingly feasible. Instead of bundling goods in trucks or trains according to a fixed schedule, cargo drones can transport fewer items more often with more flexibility. Despite the vast investments required to build UAVs of this scale, several established and new market players are racing to become operational.

US start-up Elroy Air, for example, intends to begin large commercial cargo deliveries in 2020. From loading and unloading to flight mode, the Elroy drone is completely autonomous, and can carry loads of up to 225 kg as far as 500km in its detachable pod.

Out in front: Parcel deliveries

As outlined above, both established and disruptive new players are piling into the cargo drone market and, in several cases, enjoying early success. But while only time will tell who succeeds in the long term, one use case is already outshining the rest. The parcel delivery sector’s high public relevance and advanced regulatory progress mean it is likely to define how drone air space potential will be used in the future, and how other use cases evolve.

Players in this sector will create a specific value proposition for certain customer segments, while complementing existing delivery modes. This will enable them to overcome physical barriers, such as traffic, poor roads or bodies of water, that pose significant obstacles to current delivery methods.

However, if drone-based parcel deliveries are to become commonplace, we believe it will take more than the success or dominance of a single player such as Amazon. Rather, a whole functional urban parcel delivery system will need to develop. In our follow up article, we imagine such a scenario in the city of Berlin, from considering air traffic control and coverage area to potential delivery costs. We calculate, for example, that the usable air space above Berlin could potentially – and safely – accommodate 1,200 cargo drones at any one time, enabling the delivery of around four million parcels every year.

Challenges and outlook

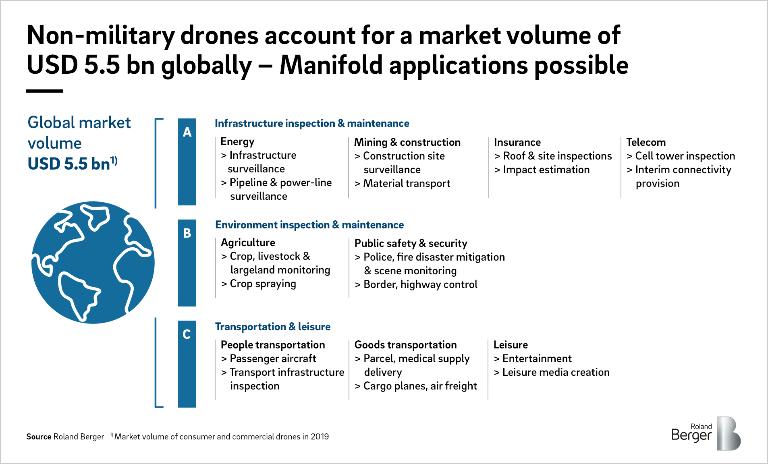

As we have seen, individual drone-based parcel delivery services are already being rolled out. The problem is, they will need to be part of an over-arching system if urban UAV delivery is to become a commercial reality. This will involve developing a framework for the system, that is, determining the conditions in which it will exist, as well as implementing the system itself. Both face hurdles.

In terms of necessary conditions, comprehensive regulations for drone operation are the number one priority. For example, will there be rules and guidelines on how to navigate drones within designated air space? What technical standards (5G?) will be required for communications between drone operators – and how will communications be standardized?

In addition, drones' interaction with the environment will need to be regulated. Where will they be allowed to land and take-off, and will restrictions be placed on operating hours to minimize noise pollution? A review of delivery drone noise by the Australian government may offer an initial insight into regulatory thinking when it reports in the coming months.

A second key condition is determining how the infrastructure of the over-arching system, such as drone landing pads and charging stations, will be organized. For example, as batteries become lighter and longer lasting, drones will become more efficient. Eventually they will be able to dispense with batteries altogether and charge as they fly using solar panels, removing the need for expensive charging infrastructure. Investments therefore need to be carefully targeted.

The challenges to implementation are discussed in our second article.

Despite these challenges, it’s clear that cargo drones have a distinct value proposition. To overcome the hurdles to large-scale implementation, the development of a collaborative ecosystem will be key. This should include national authorities, infrastructure providers and leading players to ensure standards and scaling across the industry. The recent developments highlighted in this report indicate that these parties are ready to work towards such a solution. If so, it’s likely it won’t be long before the delivery drone ecosystem is flying high.