On being human

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta26_human_equation_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

In this issue of Think:Act magazine we examine in detail what it means to be human in our complex and fast changing world now and in the days to come.

by Steven Poole

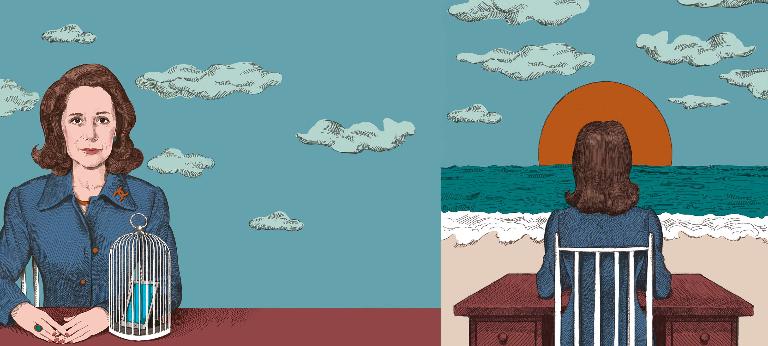

illustrations by Jeanne Detallante

Pioneering thinker and psychologist Sherry Turkle wants us to reclaim human space from all those accelerating technological interruptions. In conversation with "Think:Act", she outlines how we need to change our pace to be our most creative selves.

While the dangers and addictions of the digital world, social media and devices are a hot topic right now, they've been troubling Sherry Turkle for almost three decades. The psychologist and MIT professor first rose to fame with her book "The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit" way back in 1984, exploring children's relationships with videogames and electronic toys. Her second book, 1995's "Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet", discussed the way people could play with identity on the nascent World Wide Web. That made "Wired" magazine sit up and they put her on the cover, although she now jokes that she'll never be on the cover of that magazine again because of her increasingly critical position on how our relationship with technology has evolved: in our personal lives, in the workplace and in the public sphere.

In your famous book "The Second Self" (1984) you wrote in what was quite an optimistic way for the time about children’s relationships with videogames and electronic toys. Now videogames are a huge entertainment industry, and the WHO has just listed “gaming disorder” among new mental illnesses. Was a backlash inevitable?

No. Things took a turn they did not have to take. I’m not a technological determinist, I don’t think tech only has one way it can go. If I put my Marxist hat on, in market-driven capitalism, did it have to take this dark turn? I saw something positive… I tried to write about a psychological and educational potential that the tech had and still has. The book is a counterfactual of a direction that was not taken. That book was written before we decided that we wanted to have a tech always on and always on us, so people used the tech and exploited the tech and turned away from the tech to the betterment of relationships in other parts of their lives. Now we don’t turn away from the tech.

"The Second Self" is going to become a more relevant book, a model of using the tech and then turning away from it, not making it your mind-meld where it becomes a kind of prosthetic. That book opened a window into potentials of the technology, some of which we’ve turned away from, that tech showed a world where children wrote their own games, children learned how to program. I don’t think that every child has to become a master hacker, but not knowing this essential skill on which everything in your life is based has really put people at a terrible disadvantage.

In 2011, your book "Alone Together" talked about the loneliness and atomization experienced by people on the social networks that were advertised as bringing us together. Do you now feel vindicated that this is generally accepted, or annoyed that it took everyone else so long to catch up?

The real turning point for me was that by "Alone Together" two things had happened. First of all, there were the social robots. I’m very down on anything that has pretend empathy. Fake psychotherapy, fake therapy, we have enough trouble getting people to show the real kind and giving them experiences of fake empathy… In my research it just leads to bad things. Why don’t these children have empathy, they’ve been having these long conversations with Siri and Alexa…

Everybody’s walking around texting on their phone, making their phone the focus on their social life. I could see that flight from conversation was going to be the dominant empathy-killer.

I knew I was right because I did the research. I saw something very clearly. I’m in elementary classes, high-school students, in businesses, and I see that people aren’t having conversations and their faces [are] in their phones.

I was studying the costs because people didn’t want to see there was a cost. It feels good to not have to talk to anybody because you feel vulnerable when you talk to people. Why don’t you want to talk to your boss? It makes [you] anxious. Why don’t my students want to come talk to me during office hours? Because I’m famous. They want to seem more perfect.

It was natural that people didn’t want to hear my message – "you’re vulnerable" – it was like I was blowing the whistle.

"When we get email we tend to speed up the pace of important decisions, so try just answering by saying 'I'm thinking.'"

Do you think the ways we use technology are actually inhibiting empathy generally, as you say is true about teenagers’ avoidance of phone calls in favor of texting? Or are we retreating from empathy for some other reason and using technology to do it?

The tech is an enabler. It’s always been hard to fire somebody. But before you had to face them. Before [as per] social convention, you could write a letter but that was awkward, [so] you had coffee with them. Now it has become the social convention to text them. It’s always been hard to say difficult things to your child. Now all of a sudden you can email them. Tech takes our vulnerabilities, makes us feel a little less vulnerable. I don’t want to pretend that tech invented the difficult conversation. It takes a human vulnerability and says: 'You don’t have to do this hard thing.'

One of the funniest demos I ever went to was very early in the Internet of Things. You could order your coffee from Starbucks and the program would route you to your nearest Starbucks where you would tell it in advance all the people you didn’t want to run into. It would put you on a route that didn’t cross any of this people. They called it the friction-free life. I remember thinking, 'Who said that you never have to have a moment of friction with difficult people or difficult moments, when did that become the good life?' We use tech as an enabler to live lives where people disappear.

Friction-free first [was] meant [to be] in economic ways, but more and more [it is] socially friction-free.

The replacement of human judgment with algorithmic judgment in so many areas of life — from stock-trading to driving — seems to reflect an ideal of eliminating what is messy and unpredictable about humans. But you have argued that that is a dangerous wish to have, in areas from friendly robots to mental-health apps. How do we steer a path between being seduced by the apparent power and despotism of the algorithm, and refusing to use its potential benefits?

There are some commonsense rules. I’m very moved by the study that Google did of its workplace, where they essentially just studied all the people they hired ever since they began the company. They hired people on the philosophy that the people who’d do best were the ones who were great programmers, cool customers, whose skills were algorithmic, mathematical. It turned out that the people who succeeded in the company didn’t have those skills at all. The people who succeeded were good at conversation, high empathic skills, worked well in teams, really had everything to do with the conversational corporation.

The first thing we need to have is a little bit of humility for how far excellence in algorithmic thinking will get you when you need to work with other people and be creative. [Google] had these Alpha teams, supposed to be the greatest minds. Those were not the teams that thought up the best ideas, it was much more the teams that were collaborative. We’re at our best as people when we’re being empathic and talking together.

It’s very important to begin the discussion about the glory of the algorithm and the fantastic-ness of AI, with this example.

There are some things where obviously it’s helpful, but if you follow it blindly you’re going to get into all kinds of trouble. In the area of medical diagnosis, it turns out that physicians taking a personal history and actually sitting with a patient can see all kinds of things that the AI can’t, and you are an incompetent medical system if you take away doctors who are trained to sit with patients, do a physical exam, take a history, and know how to figure … and are just relying on data points being thrown into an AI.

This is an area where you see tremendous overreach and then correction, and that’s what we’re going to see in every field. Already in medicine there’s a sense that there’s been overreach, you’ve certainly seen it in stock trading.

It doesn’t mean that I’m a Luddite. People forget how much people can do.

Another problem is that algorithms (such as Facebook’s News Feed) increasingly decide what version of reality we will see. How do we break out of these filter bubbles while staying in touch, and not going permanently offline?

Now you’re talking about really dangerous algorithms. It’s been shown that the algorithms used on YouTube and Facebook are pushing people to extremes. The studies show that no matter where you start on YouTube, you end up with some crazy right wing or some crazy left wing theory of something, because you’re pushed to more and more radical clickbait, even if you start with something very middle of the road. You start at vanilla, and you end up at chili pepper 10 clicks away, because the algorithm is pushing you to stay more and more engaged.

I certainly think there are ways we can resist this. I don’t think you need a detox. It’s not to say that there aren’t things that are trying to addict you to the product.

I don’t think addiction is the right metaphor. If I told you that I was addicted to Methamphetamine, you’d know what needed to happen. You need to check into rehab. You’d know that that needed to be my next step. But if I tell you that I think I’m hooked on Facebook, that’s not my situation.

When they bring other pleasures and activities into their lives, and other people into their lives, and more lively and pleasant forms of being together, they’re not addicted.

They got involved in this play, they were just in this compelling activity the metaphor of addiction makes people feel helpless, we need to find a better balance.

You say that we can still use our phones for useful purposes, but should do so with greater “intention”. What’s an example of how to do this?

If you were here and we were going out to lunch, many people take their phone and they turn it off and they put it on the table face down. It turns out that in that position the conversation is both less empathic and also the topics turn to more trivial things. Using your phone with intention means that if we were having lunch and we were trying to get to know each other, you’d put your phone where you can’t see [it]. The phone takes you elsewhere, it reminds you of all of your elsewheres. When you’re with other people, you want to be with them.

The phone makes people very intolerant of moments of boredom, checking and checking, and constantly getting this new input from around the world. Conversation with people, people I interviewed said, is too slow, too boring.

One thing about using tech with intention is to put it away so you can get used to the boringness of people, the human pace, which is boring.

A professor at MIT and the author of nine books, Sherry Turkle has gained international recognition for her pioneering work in the field of human interaction with technology and the digital world.

You also talk about the value of being bored, which is linked to creativity and innovation and the opposite of using our phones for constant stimulation, and urge us to reclaim solitude. Do we need to hear more unfashionable advice like this?

Absolutely. You should allow yourself to be bored. I think this is why meditation is becoming so popular. This woman who I interviewed calls it her 8-minute rule: it takes 8 minutes to know whether a conversation is going to be fruitful, where it’s going to go anyplace. But I can’t tolerate those 8 minutes, I can’t stand the boring bits, I take out my phone…

That’s part of the appeal of meditation, people are sensing they’re antsy, they can’t take life at the human pace. [People are] walking on the beach looking at their phone. We’re starting to reach a moment of pushback.

In your most recent book "Reclaiming Conversation", you discuss humane strategies to deal with our electronic communication overload in the school and the “public square”, as well as in the workplace. What are the main things business leaders need to know about these challenges?

One of the most important case studies was the businessman who tells his secretary that he wants to be protected from all email and calls, so he can be alone to work on his presentation. He couldn’t do it. He couldn’t not be interrupted. Find your way to reclaim boredom and solitude. But begin to think about what it’s going to mean for you to reclaim boredom and solitude, because when you do, then you’re going to be able to reclaim conversation. If you can’t be by yourself, you really can’t be in a good conversation with somebody else. If you can’t tolerate listening to your own voice, you’re almost asking them to tell you who you are.

Learn that you don’t need constant input, constant stimulation, reclaim conversation with other people, go to conversation first instead of texting or email, learn what creates a conversational corporation. Don’t expect people to get back to you right away. Don’t just be communicating with people all day.

Make places in your organization where there are no phones and just talking: sacred spaces for conversation.

Also, when we get emails we tend to speed up the pace of important decisions, so try just answering by saying "I'm thinking." Watch it go viral, it's incredible. You'll get the most odd responses.

You said you welcomed Apple’s recent introduction of tools for users to manage how much time they spend on apps. But this could be seen just as big tech shunting the administrative work of a more healthy interaction with its products onto the user. You say it’s just a first step, and the next step would be for technology to change how it seduces. What kind of changes do you envisage?

It’s clear that it was the more intelligent move for them to bow before the masses of data that show that people cannot tear themselves away from what they’ve created. They are using techniques knowingly that keep people on these apps. So it’s better for them to give you tools to monitor your own behavior so you can get a grip a little bit.

The second step is being more critical about how you design the apps and do they have to be so seductive, and what ages do you want to be designing seductive apps for, and what decisions you make about how people want to use these phones? It’s a complicated thing because you don’t want to just lay that on the tech company. I can’t pick up a women’s magazine without hearing about how virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) is going to make my life better, as soon as I can experience my soap in AR it’s going to be a happier life for me. Really? That is going to be a big, big seduction, time sink, all of us, experiencing our lives in AR.

I feel that we’re not thinking this through. We really need to think about what tech we need and why.

At the same time we’re starting a movement to put our phones in our place, we’re super-hyping a whole new world that we’re going to see through our phones.

I’m starting a much more fundamental critique of how we see tech as a solution to our problems, instead of latching on to the flavor of the day.

AR and VR is an escapist place to go if you don’t like where you are politically or culturally right now. I’m very worried about a generation who don’t like where they are right now not choosing political engagement and going off to virtual reality.

The full length of the interview is only available in the online version of Think:Act magazine.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta26_human_equation_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

In this issue of Think:Act magazine we examine in detail what it means to be human in our complex and fast changing world now and in the days to come.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.