How much do you depend on trust?

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/roland_berger_think_act_magazine_trust_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

The central theme in our Think:Act magazine is trust.

by Ben Knight

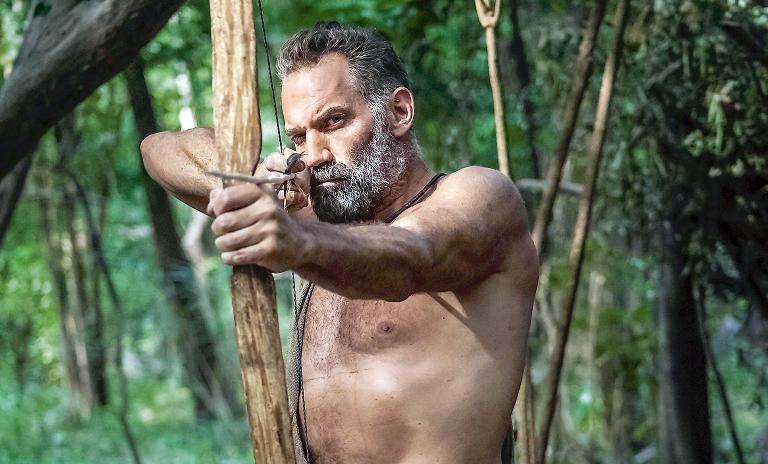

Psychology can play a key part in surviving extreme situations – and it can be applied to the business environment, too. Survival specialists Cody Lundin, EJ Snyder and William Trubridge show how.

It was monsoon season in Arizona, and Cody Lundin was out at night by a river with one of his more "aggressive" classes. That means the "tribe" couldn't bring any gear along: The only tools allowed were those they could make in the wilderness."

Of course there are no lights, because I don't allow flashlights," he reminisces. "And the river starts to roar. Flash flooding."

Throughout that night, the tribe was stranded as the river rose between them and their primitive base camp, unable to even sit or lie down because of the half-inch of water streaming around their feet. It would all have been another day at the office for Lundin, except that one participant grew scared, and said she wanted to cross the river to the camp.

"She was really scared. So we had to stand there all night and try to talk this person down," Lundin remembers. "We told really bad jokes to try to keep morale up, did squats to keep body core temperature up. But there was a point where if she would've tried to run away, I would've had to hold her down and tackle her."

"They've become more confident, because they've pushed beyond their perceived limits."

Of course, it is exactly this kind of physical misery that Lundin's students, variously determined challenge seekers from all walks of life, are here for. "As freaky as they are, those are the experiences that people like the most. That's what they joke about afterward," he laughs. "And that's because they've become more confident, because they've pushed beyond their perceived limits."

Lundin has run the Aboriginal Living Skills School in Arizona for the past 26 years and has co-hosted two of the Discovery Channel's perennially fashionable survival programs – "Dual Survival" and "Lost in the Wild". Businesspeople are grist to the survival academy mill: Companies like to send their employees into the wilderness on "team-building" and "leadership exercises". But what do they actually learn? What does exposure to nature's tough indifference have to offer businesspeople?

Lundin's teaching methods are a little startling. "When you light that fire with that half a paper match, I'm gonna bring up the person you love the most," he says. "And I make you know if you don't get this fire lit – when the snow's lightly falling, and all you have is that paper match – you and the person you love the most are dead." The point, as he puts it in his typically blunt manner, is to "prey on people's emotions and train them hard, because that's exactly what nature's gonna do."

US army veteran and celebrity survivalist EJ Snyder knows a lot about self-reliance. While out filming "Naked and Afraid" in the Tanzanian bush, Snyder got a thorn in his foot. "It festered and got so infected it was about to make me fall down because I almost couldn't walk," he says. "After about 15 days, I had my knife heating up, getting ready to cauterize the wound and clean it out. And the executive producer stepped in, this British guy, and said, 'Hey EJ, what are you planning to do with that knife, mate?'"

A former infantryman and paratrooper in the US Army with a SERE (Survival Evasion Resistance Escape) survival school background, EJ Snyder taught future Green Berets at Fort Bragg before becoming a technical advisor, commentator and host for TV and film.

Snyder's answer was a careful balance of patient explanation and pain-fueled irritation: "'Well, Steve, I'm gonna take this knife and I'm gonna shove it in this foot, and I'm gonna burn this thorn out with all this infection, and then I'm gonna take that hot, boiling water right there, and I'm gonna clean it, close it up, and I'm done.' And he's like, 'Hold that thought, mate.' And so he called time out and got a doctor in to take care of it."

In some places, though, there won't be anyone there to help. William Trubridge has not only forced his body beyond its own limits, but has put it in places that no other human body has ever faced – diving without oxygen through the Blue Hole, off Dahab, Egypt – a 98-foot tunnel 180 feet underwater that leads into the Red Sea. The soft-spoken 36-year-old is possibly the world's most renowned diver. Born in the UK, raised in New Zealand and trained in his teenage years by the legendary Umberto Pelizzari in Italy, he has broken virtually all the freediving world records that there are.

Swimming straight down beyond the reach of sunlight involves a Zen-like depth of concentration. Freediving is almost unique among sports in that, physiologically, it demands an extreme mental detachment because the brain uses 20% of the body's precious oxygen even at rest – and an active brain even more. That's why learning to deal with anxiety, particularly ahead of a world record attempt, is vital.

He describes the stress he puts himself through in training and performance: "Even if I've done that dive before," he says, "the concept of 'in five or 10 minutes you're going to stop breathing and swim for four minutes down and up, and if anything goes wrong, if you overstretch yourself just a little bit, you may black out below the surface,'" is still a challenge.

Freediving is an intense form of physical exercise and Trubridge has to try to shut down blood flow to the extremities of his body so that his muscles work anaerobically (meaning they use as little oxygen as possible). That leaves most of the oxygen concentrated in his heart, lungs and brain.

Trubridge effectively wants to shut down conscious thought while diving. "The best way to do that is not to fight the thoughts or push them out of your mind, but rather to let them slide through and focus on the empty spaces between thoughts."

To enhance this concentration, Trubridge closes his eyes during his dives so that he can feel more acutely what's going on inside his body and his mind: "Possibly more than most sports, freediving is dependent on being calm and composed and able to control your thoughts and your stress, and staying detached from what's going on around you."

"We have to manage acute stress… You know it's coming and you can prepare for it."

It's a long way from EJ Snyder's life, which, when it's not about hacking through Amazonian marshes, follows a more sedate routine of teaching survival courses to civilians, often incorporating stressors into teamwork exercises: "I'll say, 'Alright, we're building a shelter, you're in charge, and you're the worker bees.' And halfway through the project – 'You three are out of the picture!' – then the others have got to finish and figure out who's in charge. When you have a bunch of workers who are self-motivated, it just makes a better team. What CEO doesn't want to strengthen their team so they work better for them?"

But does surviving real disasters equip you for normal life? John Leach, psychologist, former military survival instructor and author of the seminal book "Survival Psychology" is skeptical that survival skills can easily be adapted to business skills.

"I'm always a little bit wary of these things," he says. "If you get into a survival situation, you don't bounce back to where you were – you come out of it a different person." In fact, many people find it difficult to relate to normal society, never mind start a business. "The bits of your brain that have been trained to be on high alert in the hostile place have not been de- trained when you come back," as he puts it.

Nevertheless, Leach can see why parallels might be drawn. A key element of military survival training subjects soldiers to "stress inoculation" – being taken hostage or being trapped in a helicopter that has ditched upside-down in water. They do this not just to learn what to do, but also to experience what it's like, so that the initial shock doesn't suspend the brain's cognitive skills.

A 15-time world record holder in freediving, William Trubridge is also the current freediving champion and holds the title of 2010 and 2011 World Absolute Freediver. His diving school, Vertical Blue, is located in the Bahamas and offers annual courses at all levels. It also hosts the annual Suunto Vertical Blue competition.

Leach has found that the temporary lack of these cognitive skills is why some people die in extreme situations and others survive. In other words, extreme situations don't directly teach you skills that you can learn in normal life. "But the principles of survival – protection, location, water, food – apply to all environments, and I don't see why those principles should not apply to the survival of a business."

Trubridge reckons that it "probably hinges on the idea of stress." He adds: " In business there's continuous background stress as well as a more acute stress in particular moments. With freediving, we have to manage that more acute stress in what I would say are almost laboratory conditions. You know it's coming and you can prepare for it and train yourself."

Maybe that is the key: You might not yet be able to dive through an underwater cave or cauterize an infected foot with a heated knife, but there is also no stressor – either acute or background, in wilderness or in life – that you can't train yourself to manage.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/roland_berger_think_act_magazine_trust_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

The central theme in our Think:Act magazine is trust.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.