On being human

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta26_human_equation_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

In this issue of Think:Act magazine we examine in detail what it means to be human in our complex and fast changing world now and in the days to come.

by Neelima Mahajan

photos by Winni Wintermeyer

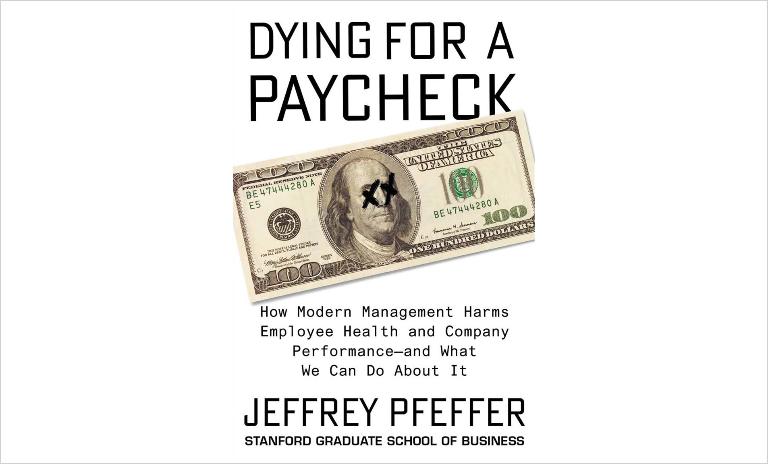

Organizational behavior expert Jeffrey Pfeffer says that modern work practices are turning organizations into death traps and if you are stuck in such a workplace, you better get out before it kills you.

The modern workplace has turned into the corporate equivalent of the Hunger Games with people working faster, harder and longer – just to survive. Jeffrey Pfeffer, the Thomas D. Dee II professor of organizational behavior at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, is calling the bluff on these unsustain-able work practices in his book, "Dying for a Paycheck". In the book, Pfeffer – who has carved out quite the reputation for his commonsensical view of management and his repeated denouncements of toxic work environments – makes the stunning reveal that the workplace is the fifth-biggest cause of death in the US. Other countries, though not covered by this research, aren't likely to fare any better. Interestingly, making people work harder is also not helping companies. In this interview, Pfeffer calls on organizations to think about the human costs involved in the relentless pursuit of increasing productivity.

Your research throws up the interesting data point that the workplace is the fifth biggest cause of death in the US. What's the situation like in other countries?

We did not look specifically at any other countries in any detail, but I did cite in the book, of course, the data. There's an article published in China that suggests 1,000,000 people a year are dying from overwork in China. I used the suicides at Foxconn as an example. I also talk about a little bit the idea in Japan of death from overwork, which the Ministry of Labor had as a category for cause of death. So, this is a worldwide problem, it is a problem even in Europe, which doesn't think it has a problem, because many of the European countries are facing some of the same pressures: layoffs where there [weren't before], and economic insecurity is awful to people's health. The gig economy is growing everywhere [and] also contributes to economic insecurity. Work hours, while they're not as long as in the US and possibly China or Korea, are getting longer around the world. Everybody believes that the only way to compete is to work forever, or work long hours. Many of the factors that I think have influenced health in the US affect other countries as well. The one big difference, of course, is that in Europe you have access to healthcare regardless of your employment status, which is a huge issue in the US because the absence of being able to access healthcare leads to all kinds of health problems, including death.

Your research shows that the impact of the workplace is equally bad for white-collar and blue-collar workers. How did things get so bad for white-collar workers?

White-collar workers have an enormous amount of stress put on them. They are working enormous hours, and taking various drugs to [stay] awake all night. Sleep is important and sleep deprivation weakens the immune system. White-collar workers are now as subject to layoffs as blue-collar workers. Work-family conflict is an enormous source of stress. Stress affects everybody, not just blue-collar workers, more so white collar workers, who are more likely to check email at home, and while on vacation, and believe that because they are so indispensable for their organization, they have to work all the time.

On the face of it, organizations appear to be thinking more about employee welfare – we've seen wellness programs, on-site laundries, Michelin star chefs employed in offices. Why does none of this make a difference?

[Instead of] having a stress reduction class, you want to have a stress prevention class. Remediation is less effective than prevention. Many of these things are [like] band-aids: so I'm going to give you healthy food during the day, but in the evening, if you look at what goes on, at least in Silicon Valley, the fat and sugars come out, so that people can do their second shift. You see gyms. I talked to somebody who said, "If I actually was in the gym, my boss would say, 'Why are you in the gym, as opposed to working?'” Companies have tried to control healthcare costs. But they don't deal with the fundamental issues: they don't deal with work-family balance [and] economic insecurity. They don't deal with job control: people are being micromanaged, and every keystroke is being monitored. Until we address the fundamental elements of the work environment, not much is going to change.

Somehow people are never part of the equation when we talk of business today. Companies – like you mention in the book – would much rather talk about their environmental impact, and not even think about the human impact. Why?

When you work for a company, you entrust, in a very fundamental way, your psychological and physical well-being to that organization. I don't think organizations want to take that responsibility seriously. Many say, “Well, people are agentic.” That if people are so stressed at work, they ought to get another job. The presumption is that polar bears can't take care of themselves, but people can. It is kind of a free market individualism idea that people need to be left alone to do whatever they want. And if people want to work themselves to death, they can.

"We need to take human health and human life way more seriously."

How could we change this paradigm of thinking where people are viewed not just as cogs in wheels?

We need to worry about human sustainability, about people's well-being, and human health. If you look at the indicators, they talk about education, but they [also] talk about health and well-being as another indicator of how well a society functions. It's interesting that in the US now, the difference in lifespan between the healthiest and the least healthy counties is 20 years! That difference in lifespan across the world is 40 years, between the countries with the best and least long lifespan. So we have enormous issues of health inequality, in which many people have been consigned to a very short life. We need to take human health and human life way more seriously, and not just worry about GDP and profits.

Most of what we have done is not good for the companies either. There are surveys that demonstrate that stress leads to turnover and turnover is expensive. When people work and they're not healthy, they're less productive. Long work hours are inversely related to productivity. Lay-offs actually do not improve stock price or productivity or profitability. We've created a really a lose-lose situation in which companies are having trouble retaining their employees and getting them to be productive, employees are getting stressed out and sick, and nobody's benefiting.

Would it be a good idea for companies to adopt a metric like the human sustainability index? How should they measure it?

It's hard. There's a bunch of things they could measure. One, self-reported health, which prospectively predicts mortality and morbidity. You can just add to your survey, one, what's the current position of your health, two, companies can look at the prescription drug use of employees. If you looked at what percentage of the company's workforce was on ADHD drugs to try to keep themselves awake or sleeping pills or antidepressants or other forms of psychotropics, that would tell you a lot because in healthy workplaces, people do not need to take all these medicines to survive.

When there is environmental damage, governments can hold companies accountable. Should governments look into this, measure it or enforce it?

Yes. Years ago in the US and elsewhere, governments got involved in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to reduce workplace accidents. In many cases, because of governmental attention and workers' compensation claims, the rate of physical injury has gone way down. But there is this psychological injury because of workplace stress. The UK reports each year, the number of lost workdays due to absence and what percentage of those absences are due to stress, and the percentage is quite high. The US and UK governments report what this is costing the economy and the Australian and Canadian governments have done similar reports. But what the governments have not yet been quite willing to do, is to say, "This is costing the larger society a lot of money. Because when I make somebody sick in the UK, of course, the UK is paying because of the National Health Service." At some point, the government needs to say, “I will not let companies externalize their cost onto the larger society.” There is enormous awareness about the severity and the cost of the problem. Thus far, no one has been willing to take the bull by the horns. As healthcare costs continue to rise inexorably, and as countries believe they can't afford them, they're going to have to do something about the workplace, because it is one enormous source of the problem.

For most workers walking away from toxic workplaces is not an option because of economic reasons. So they're stuck in this Hunger Games-like scenario where just to survive, they need to work more and harder, faster, better. If their workplaces don't change, how can employees find their sanity?

Morten Hansen has published a book called "Great at Work" in which he studied 5,000 people, and found that the high performers, in fact, work fewer hours. So this idea that you're going to win at the Hunger Games, I love the term, by working more hours isn't going to work. You need to work smarter, not longer. When you're exhausted, you're not going to be very efficient [or] creative. I just had lunch with a woman [who is] a 34-year-old Harvard MBA, and was working ironically, for a healthcare company, and she's quit.

Her supervisor who's a little bit older than her has had two strokes.

The toll is enormous, and particularly for women, who often believe they have more discretion about this. The United States has the smallest proportion of college-educated, working-age women in the labor force of any of the major industrialized countries and that's in part because we make the workplace so difficult. She's got a husband who works, so she's quit. Think about the investment that's been made in her and her career and now she feels she can't work. The loss to society is enormous!

If the workplace is already killing you, you need to get out! In every industry, there are better and worse employers and when people stop putting up with how they are being treated at work, maybe the employers will change what they're doing.

The gig economy has worsened the situation for workers: the apparent flexibility has its downsides. The future looks even more complicated with the rise of human-machine and human-algorithm collaborations. How will we reconcile the more emotional human aspects with the more binary technological and digital aspects in the future?

I have no idea what the future is going to be. The rise of Uber in New York City has depressed the value of taxi medallions, and the income of taxi drivers. There are regular reports on suicides by taxi drivers. Society faces a fundamental question: What priority do we put on human life and well-being? At the moment, I think we don't give it nearly enough priority. The number one thing that needs to change is when you look at people, you need to see them as people [and not as] factors of production or as resources. You need to understand that when they come to work for your organization, they have placed their well-being in your hands. The leaders of these organizations need to take that responsibility much more seriously than they currently do.

Today work has become a disproportionate part of life, eating into our priorities. Is there a need to reframe our understanding of what work ought to be?

Possibly. A 100 or 200 years ago, people actually worked much longer hours because they had to work harder just to scrape out a living. The irony is that the industrial age was supposed to free people. In some sense, for a while I guess it did, but there's been a shift in the balance of power. In the 1930s, 1940s or 1950s there were reasonably strong labor unions in the US, and certainly in Western Europe. Unions are declining all over the world. So nothing is balancing the power of capital. There is no countervailing force to say we ought to care about people. It is all about money. Unless that changes, I'm not very optimistic.

A lot of governments have standards such as minimum wage or basic health safety requirements. Do we need to reframe the standards of what constitutes healthy work, even in psychological terms?

That's a great question. The interesting thing about those work standards is that they do not apply to wide segments of the workforce. In Spain there is a significant fraction of the workforce that is working under contract, and their contract work is not covered by some of these protections. In the US there are employees who are not covered by many overtime rules. So a lot of the protections ought to be expanded to apply to psychological stress not just physical workplace hazards. Two, they need to apply to more people. Take France, which has a working hour limit law. I say to [the French], it must be nice because you have the 35-hour work week and they laugh because the law partly doesn't seem to apply to them. At least they're taking vacations which people in the US tend not to. Blue collar workers have to be covered by these regulations. White collar workers tend not to be and so, they are at the mercy of their employers' discretion.

A professor at Stanford University Graduate School of Business, Jeffrey Pfeffer's broad scope of interests has led him to pen 14 books on topics ranging from the knowing-doing gap and power in organizations to human resource management and resource dependence theory. In 2015, he was named to the Top 25 of the Thinkers50.

In your book you talk of Patagonia and this idea of "management by absence" where there is no need for extreme management and people can just simply go about doing what they need to do. Is that a solution to building better workplaces?

That's right. The absence of job control, coupled with high job demands leads to an enormous increase in cardiovascular disease. Giving people more autonomy on the job causes them to be more motivated and engaged.

Have you seen any companies that have actually made the transition from very traditional models to something which is a bit more like what you describe?

One of the companies that made that transition is Barry-Wehmiller. If you were to talk to Bob Chapman, he will tell you that he did not always manage in the way he manages today, so this was a change that he made. The company was close to bankruptcy and he got it out of bankruptcy and then one day he had this realization that everybody who came to work was someone's precious family member, and he had a responsibility to send those people home at the end of the day, in better shape than when they arrived. [So] he changed a bunch of stuff Organizations change if they are serious about it. And the change doesn't actually take that long and it doesn't cost that much money. It doesn't actually cost anything.

The full length of the interview is only available in the online version of Think:Act magazine.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta26_human_equation_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

In this issue of Think:Act magazine we examine in detail what it means to be human in our complex and fast changing world now and in the days to come.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/ta26_human_equation_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

In this issue of Think:Act magazine we examine in detail what it means to be human in our complex and fast changing world now and in the days to come.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.