The global use of innovative mobility concepts like bike sharing booms.

Think:Act Magazine "Own the Future"

The rise and fall of Chinese bike-sharing startups

Think:Act Magazine

How short-sighted vision turned a Chinese success story into a cautionary tale

Massive investment drives new ideas, but in Chinese entrepreneurial culture, it is also creating a dangerous dog-eat-dog world. The result? Short-sighted visions are highly prized, but their fast-paced strategies can fail to deliver long-term success – with painful results.

A spectacularly fast rise to fame, followed by an even faster and more dramatic fall – that is the story of Ofo. The Chinese bike-sharing company grew from obscurity to a valuation of around $3 billion at its highest point. Then, suddenly, its fortunes turned and it found itself close to bankruptcy. Even in the fast-paced world of Chinese startups, Ofo's rollercoaster ride on two wheels is turning heads and raising questions for a whole new industry, and not only in China. Briefly touted by China's national TV station CGTN as one of the country's first real inventions since paper or gunpowder, bike-sharing now seems likely to go down in history a bit differently: as the business model behind one of the biggest startup failures ever.

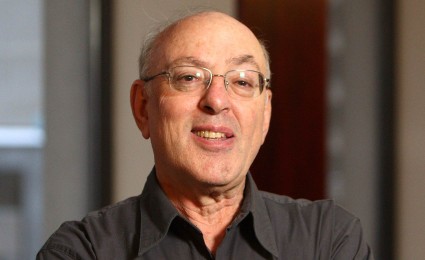

Every bike-sharing startup has a signature color to stand out on city streets, and Ofo branded its five-year existence with yellow – a lemon hue which can now be seen dotting the many bicycle graveyards where the company's fleet are now being dumped. "This is a Harvard business case in waiting," says Jeffrey Towson, professor of investment at Peking University's Guanghua School of Management. That school also happens to be where Ofo's story began. Dai Wei was a student at Towson's institute when he and four other members of the cycling club bought some bikes and placed them at the campus gates in the spring of 2014. Students could scan a QR code on the frame of the bike with their smartphones, download an app to pay a small deposit, and – click – the bike's lock snapped open. Welcome to your "shared" bike, which you could ride for around 15 cents for each hour. Inspired by "ride-sharing" taxi apps, people started to call this "bike-sharing."

Even after raising prices, Ofo couldn't seem to earn back that kind of money.

What happened next evokes comparisons not so much with just gunpowder, but fireworks. A $1.4 million seed investment by Hongdao Capital and Will Hunting Capital was quickly followed by more and more big investors who wanted to place their bets. A series C round of $130 million was followed by a series D with $450 million, and then $700 million and $866 million from investors like DiDi Chuxing, the Chinese Uber, and others led by the Alibaba Group in July 2017 and March 2018. Before the fireworks came to an abrupt halt, Ofo had raised a whopping $2.2 billion.

But in the summer of 2018, four years after Ofo was founded, the company came close to bankruptcy. Even after raising its prices, Ofo couldn't seem to earn back that kind of money. After complaining about "immense" cash-flow pressure in an internal letter to employees, both investors and customers abandoned Ofo. Dai Wei compared his situation to Winston Churchill's after the Dunkirk disaster, inviting his core team to "fight until the end," the South China Morning Post reported. Employees who had once proudly bragged that their company had "too much money to spend" and could never fail were now looking down from their office windows at crowds of angry customers lining up to demand their deposit back. The company had to lay off most of its staff, and at the time of writing, the yellow bikes were quickly disappearing from the streets of Beijing, Shanghai, Singapore and Paris.

Explanations of what exactly went wrong are still evolving, but it seems likely that the mind-boggling amounts of cash pumped into what wasn't essentially a "bike-sharing" model, but rather a rental business pepped up by a smartphone app, had something to do with it. Yes, the company bought bikes and placed them in the streets without docks for anybody to use, and that was somewhat new. And yes, a smartphone app served as the key. But the company owned the bikes, just like any old-fashioned rental shop, and incurred huge maintenance costs. The word "bike-sharing," however, made investors as giddy as if they had been doped for the Tour de France.

"Ofo was hijacked by capital," says Zhang Yi, the founder of Chinese internet research company iiMedia. "A weak management team embarked on a too fast an expansion." Even the employees felt the money arrived a bit too easily. "We felt the investment we got was way more than the capital we needed," the business magazine Caijing quoted a former Ofo employee in December 2018.

Ofo ordered bikes from manufacturers by the millions and distributed its yellow bikes not just in China, but in cities around the world. While members of Ofo's founders team ordered Tesla luxury cars for themselves, many of the bike manufacturers are now going unpaid. "This was a typical liquidity bubble like we keep seeing periodically here in China," says Michael Pettis, a professor of finance at Peking University. "It is way too easy in China to raise money." Pettis lives in the center of Beijing. When leaving his home to walk to the subway, he was suddenly forced to "walk on the street, because the sidewalk had disappeared under heaps of bicycles." For a while it looked as if this Chinese "invention" had the potential to make cities around the world more environmentally friendly, a green mobility solution for the so-called "last mile" from subway stations to peoples' homes and offices. There was the promise of fewer cars on the roads, less pollution and a healthier consumer. In a relatively short time, more than 30 bike-sharing competitors to Ofo sprung up in China, aggravating the company's troubles. Each picked a different color, until every shade of the rainbow carried a trademark.

What happened with Ofo is actually not unusual for Chinese startups.

All over the world, people are now shaking their heads over photographs of yellow bikes dumped as waste metal. The Ofo disaster has threatened how attractive the "sharing economy" is for investors – and their appetite for the future of mobility. "In my opinion, Ofo can serve as a metaphor for the overall market here in China," says Pettis. "Investors are very speculative here. Every kind of crap can reach incredible valuations." The ingredients for rational investment patterns are still in short supply in China, says the finance professor, from "good corporate governance to a stable macro-economic environment and transparency." It is, others say, a form of high-stakes gambling. "Ofo spent too much money too fast," concludes his colleague Jeffrey Towson.

What happened with Ofo is actually not unusual for Chinese startups. Especially in the internet and business-to-consumer (B2C) space, investors zero in on two or three companies in emerging industries and then equip them with mind-boggling amounts of cash to quickly acquire customers and grab market share. Then the race is on. "If you are not the number one or number two in your space, you quickly die," says Towson. While this kind of "VC2C-investing" (venture capital to consumer) that subsidizes the customer acquisition of loss-making companies, is also seen in Silicon Valley or elsewhere, what makes China stand out is the "ferociousness" of competition, says Towson. "These Chinese companies are out to kill each other. Spending lots of money is necessary, and if your competitor gets a billion dollars and you don't, you fall behind."

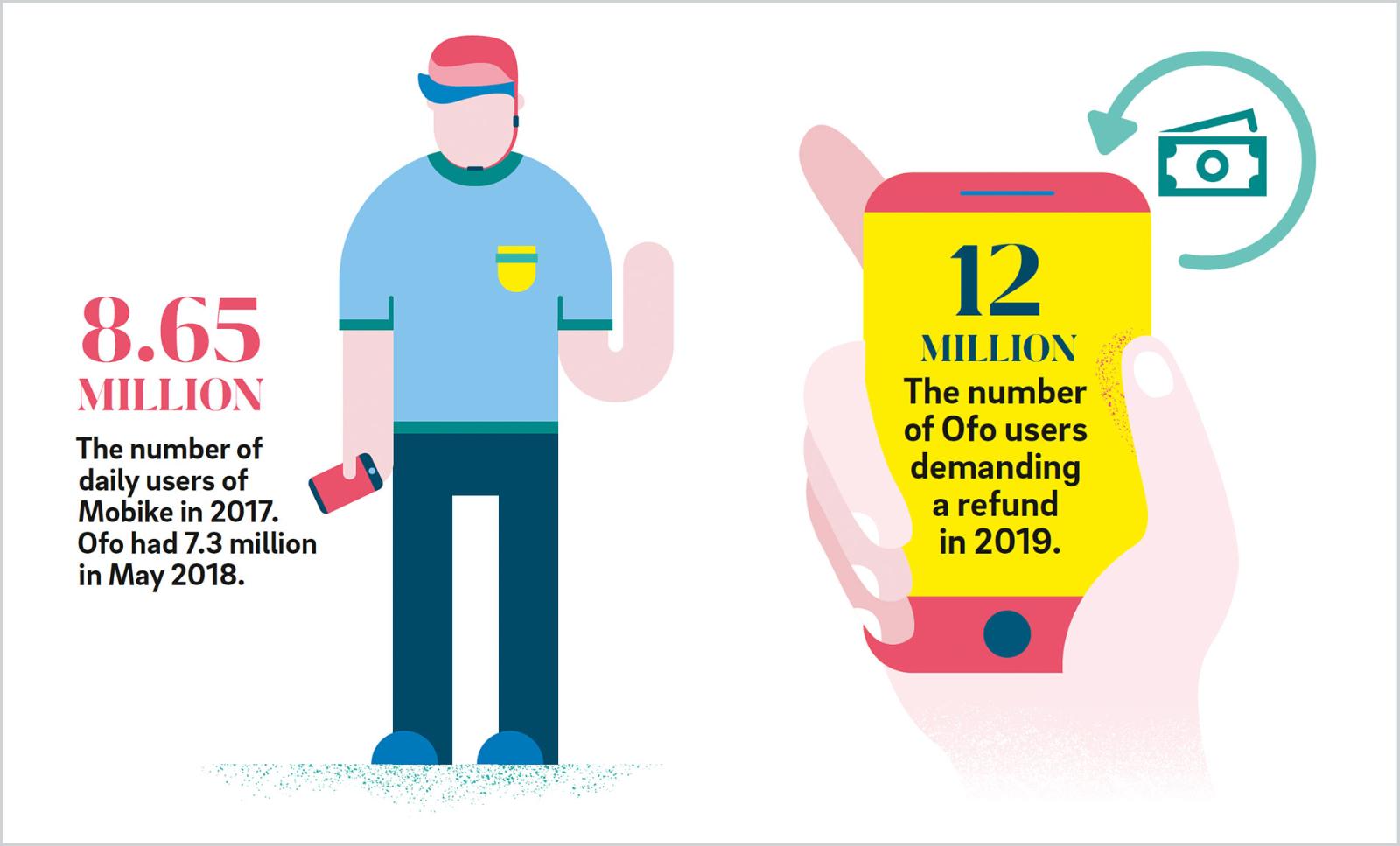

Ofo's biggest competitor in bike-sharing was Mobike, which engaged Ofo in a fierce battle for market share. Just like in the ride-sharing industry for taxi rides, for example between Uber and DiDi Chuxing in China, consumers were lured with massively subsidized prices by both competitors, funded on each side with money from investors who had been told that profits would eventually follow. Suddenly, there were even more orange bikes on Beijing's streets than yellow ones. Uber finally gave up in China. And Mobike was acquired in April 2018 by Meituan-Dianping, a Chinese giant that has started to build a "super app" offering consumers everything from restaurant reviews to online retail and hotel bookings, taxi rides – and now bike rides.

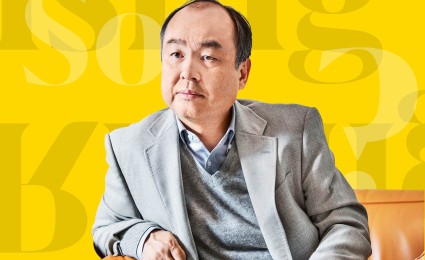

Now 28 years old, Dai Wei founded Ofo in 2014 with a few fellow students he knew from Peking University's cycling club. The group did not know much about running a business, but they were very good at luring investors with colorful presentations and catchy buzzwords and phrases like "sharing economy" and the "free deployment of assets." The craze of fundraising that followed was aided by media hype and self-declared "digital China ecosystem experts" that touted Ofo's bike rentals via smartphone as yet further proof of "that skillful Chinese micro-innovating game." The company is now almost bankrupt and is said to owe suppliers at least $28.6 million.

Some analysts believe that Ofo's failure to look for a similar exit via M&A was the real reason for its demise. There have been reports that Ofo founder Dai Wei offended executives sent to his headquarters by the ride-sharing giant DiDi, who then walked away and also vetoed new investment rounds in Ofo. Only Mobike, now set to be rebranded as "Meituan Bikes," succeeded to transition from a stand-alone business to one of many products in a platform business before it ran out of investors' money. "Bike-sharing may not be a sustainable business model, but it is a great service," says Towson, who likes to use the bikes.

Following the logic of platform businesses like Meituan-Dianping, which is to get as many users as possible and then sell them whatever you can, the decision to acquire a loss-making bike-sharing company with a big database of users may make a certain amount of sense. It's too early to tell, however, just how much appetite for loss Meituan-Dianping has, and Mobike has continued to make losses. China's current winner of the bike-sharing race reported $22 million in revenue from the takeover date on April 4 until the end of the same month, but an overall loss of $75.1 million, according to the news portal Sina. And Meituan's latest financial report in March 2019 put Mobike's revenue since the acquisition at $223 million, which is contrasted by a loss of $680 million. "There are a lot of variables in this kind of business model, like the repair cost for the bikes, operational costs for moving them around and asset depreciation," says Rui Ma, co-host of the popular TechBuzz China podcast, who shuttles between Beijing and San Francisco.

Investors don't seem to care much about losses in such types of businesses – neither with bike-sharing companies in China nor with the now popular scooter rental companies in the US and Europe – as long as they can claim a successful exit at some point. It will be up to the shareholders of companies that acquire bike-sharing services to find out if the business model is sustainable in the long run.

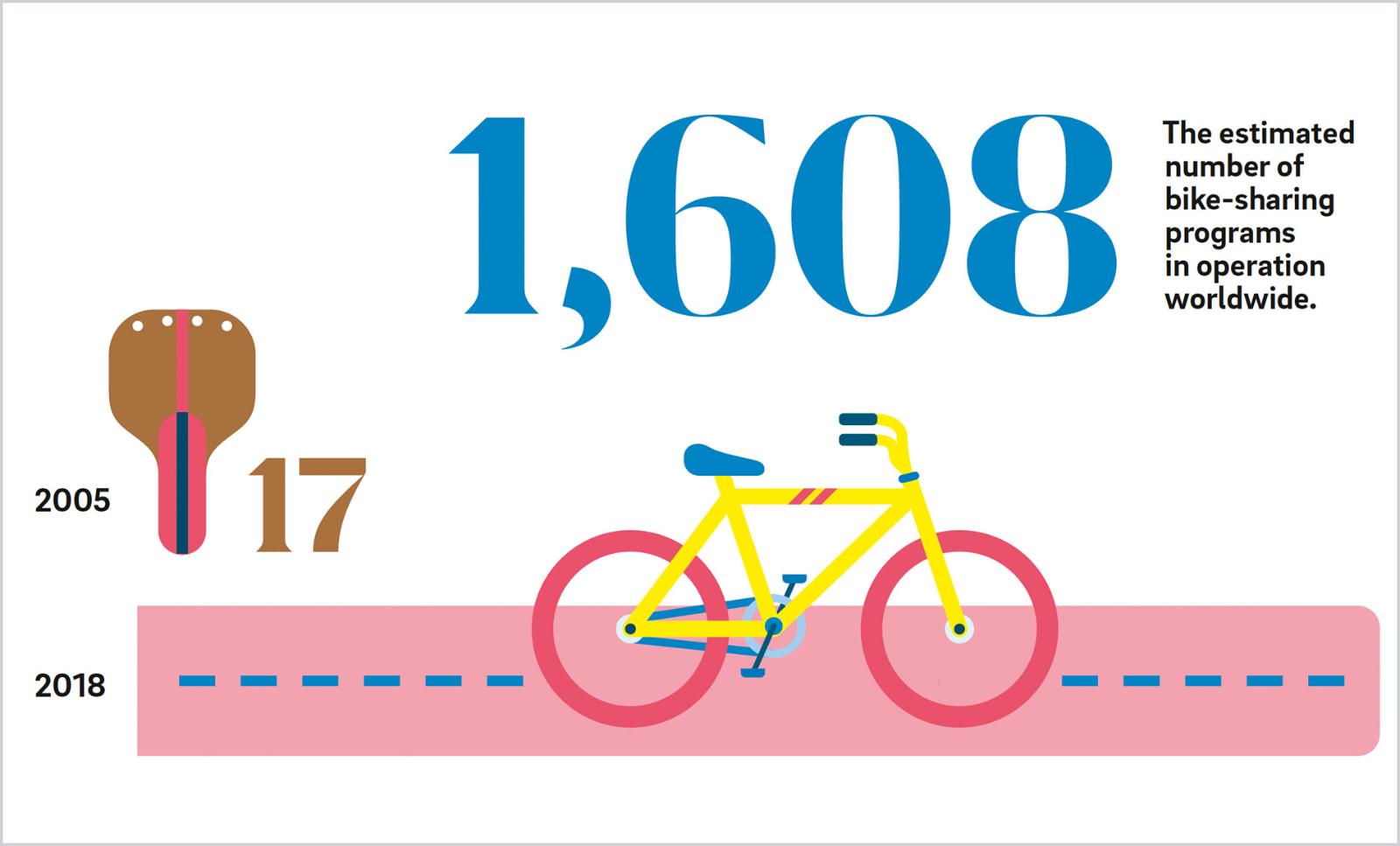

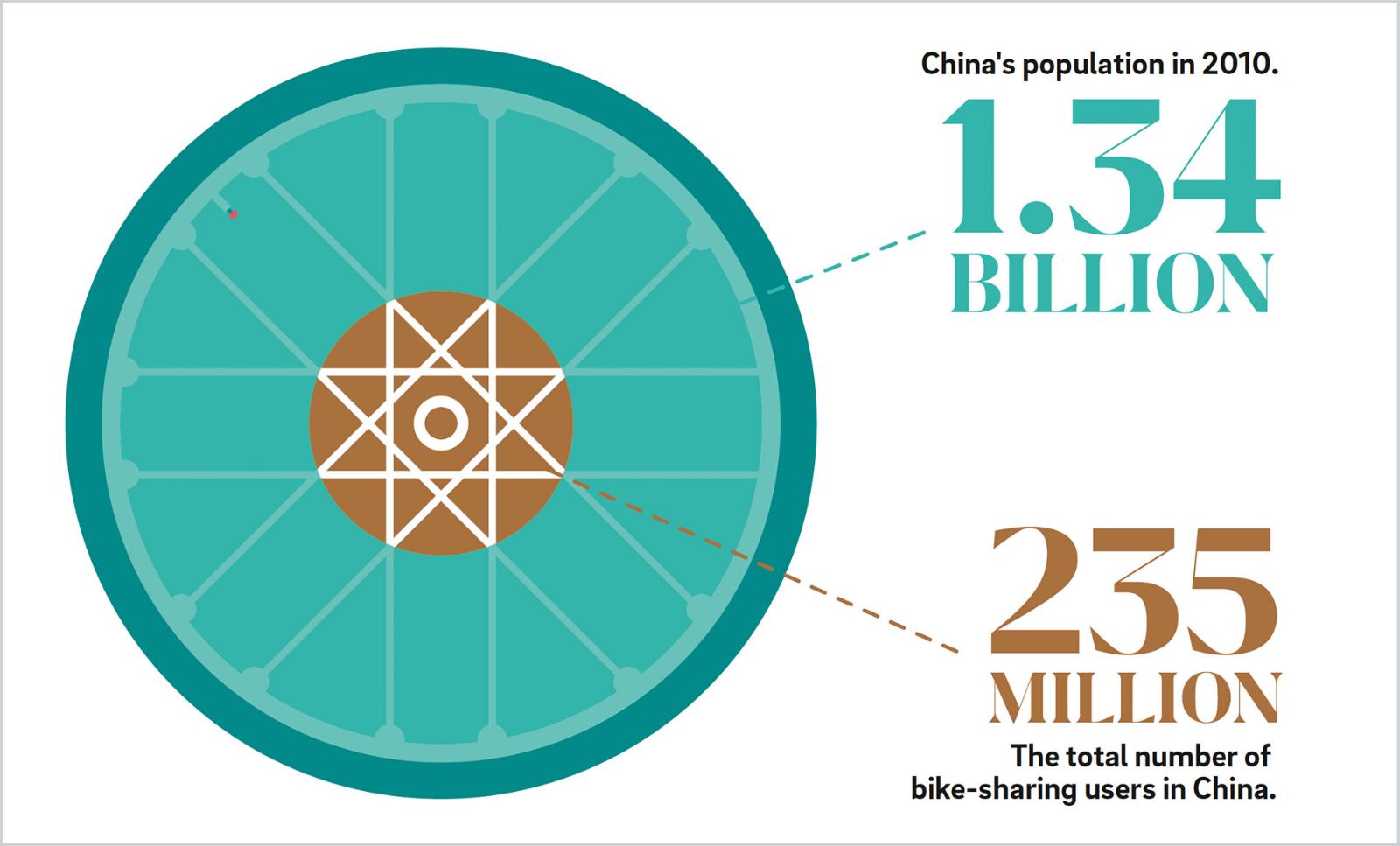

Peddling figures for the new cycle apps

For some the appeal may lie in never having to change a flat tire, for others it may be the flexibility to walk and ride at will or not needing to find a secure place to lock up – whatever the reason, there's no denying that bike-sharing has managed to catch the public mood. Here's a quick look at the rise and fall of the two-wheeled trend.

Your path to tomorrow, today

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/tam_future_cover_en_download_preview.jpg)

The actions of the present lay the foundations for the future. What does this saying mean in turbulent times? Consider a mix of solidity and flexibility!

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.